Bessie Blount’s grandchildren clearly remember their steely, diminutive grandmother regaling them with tales of her many accomplishments as a physical therapist, inventor and forensic handwriting analyst, who used her skills, in part, to help law enforcement solve cases of embezzlement and forgery.

Blount’s achievements were all the more impressive because of the obstacles and skepticism she faced as a Black woman in her profession. She died at age 95 in 2009 at her home in Newfield, New Jersey.

“The frustrations of the time. Not having access. No one buying your inventions. Not being accepted,” her grandson Aaron Griffin of Delaware tells A&E True Crime. “[Her attitude] was like, ‘OK, I’ll show you.'”

“She tooted her own horn quite frequently,” her grandson Nicholas Griffin of North Carolina tells A&E True Crime.

Blount was passionate about handwriting analysis, believing it signals everything about a person— including feelings, mental health and even physical ailments, her grandsons say. Once, Blount took a look at her grandson Nicholas’s handwriting at age 12 and correctly diagnosed him with weak vision in one eye.

“She said it was all in your writing, that your writing showed you how you were physically as well as mentally,” Nicholas Griffin says. “It’s a bit of science but it’s a bit of a gift–and that’s what she had as well.”

Born in Virginia in 1914, Blount studied nursing and physical therapy in New Jersey. She then became a licensed physiotherapist and was hired at Bronx Hospital, now Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center, in New York.

She is best known for inventing an automatic feeder for patients without limbs. She received patent No. 2550554 in 1951 for her invention, but after the Veterans Administration expressed disinterest, she signed the patent’s rights to the French government, which saw use for it in its own military hospitals. She invented a number of other devices but never patented them, her family says.

At Bronx Hospital, Blount also taught patients to write with their mouths and feet, a skill she developed herself as a willful young girl after a teacher rapped on her knuckles to admonish her for writing with her left hand.

Blount became intrigued by handwriting analysis after observing her patients’ penmanship changing along with their condition. She attended workshops and seminars, and eventually started giving lectures on the topic, according to newspaper stories.

“Bessie bristles at the slightest suggestion that her handwriting analyses are the scribblings of a self-styled seer rather than scientific revelations,” says a September 1958 story in the Philadelphia Tribune that mentions Blount embarking on a Southern lecture tour.

Blount published a paper in 1968 titled “Medical Graphology” whose foreword cites M. N. Bunker, founder of The American Institute of Grapho-Analysis, later renamed the International Grapho-Analysis Society. “Bessie Blount is a remarkable woman,” Bunker was quoted. “She is a vital speaker, one who has the enthusiasm and remarkable accomplishments to hold her audience.”

Graphology is the analysis of handwriting for behavioral profiling, and Blount’s paper explored the “trait stroke” method, which postulates that each stroke corresponds to a personality trait, Sheila Lowe, president of the American Handwriting Analysis Foundation (AHAF) tells A&E True Crime. Bunker was very selective about who was accepted into his courses, so “if he liked [Blount’s paper] and she was part of that group, it was a big honor,” she says.

Blount, who was a founding member of the American Association of Handwriting Analysts, went on to tackle forensic document examination for handwriting authentication. She handled cases of embezzlement and forgery, and became a handwriting consultant for the Vineland, N.J., Police Department, lecturing officers and testifying in court cases, according to a 1969 article in The Daily Journal newspaper.

“I have been taught that a person’s signature is his ‘written’ fingerprints and [they] are just as valid as those on his fingers or the sole prints of his feet,” she wrote in a 1970 letter to the newspaper. She also consulted for the police department in Portsmouth, Virginia.

Blount would have been among few, if any, handwriting experts of color at the time, and would have had to prove herself to work with law enforcement, Lowe says. “Back then, especially, a lot of people treated [handwriting analysis] sort of like it was astrology or palm reading,” she says.

Handwriting analyst Linda Larson, vice president of the AHAF, tells A&E True Crime that sometime in the mid-1970s Blount spoke at a convention in California. Blount was asked to demonstrate how she taught amputees to write with their feet, so she asked the women in the audience to take off their pantyhose so they could place a pen between their toes. “She told the men they should shut their eyes for a couple of minutes,” Larson says, adding this is a story she heard many times from the late Dorothy Hodos, a founder of AHAF.

“Dorothy laughed and laughed [at telling the story]; it was pure chaos and laughter,” Larson says.

In 1977, Blount was accepted, at age 63, into an advanced studies course in the document division of the Metropolitan Police Forensic Science Laboratory, also known as Scotland Yard. She’s believed to be the first Black woman to accomplish that, according to her family.

“She was very stubborn. She wanted to be the first at anything,” grandson Aaron Griffin says.

Blount later returned home to New Jersey to her handwriting consulting business. “She offered her expertise in handwriting to museums and historians by reading, interpreting and determining the authenticity of historical documents, including Native American treaties and papers relating to the slave trade and the Civil War,” according to Smithsonian.

To authenticate historical documents, Blount would have had to study the writing style of the times, Lowe says. “When you are talking about really old documents, it’s a specialty,” she says.

In her later years, Blount was active in the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives and served as president of its South Jersey chapter.

Blount was sponsored into the organization in 1991 by John S. Pritchard III, a well-respected law enforcement officer known for tackling organized crime, according to Dwayne Crawford, the organization’s executive director. At the time, Pritchard was inspector general for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority in New York.

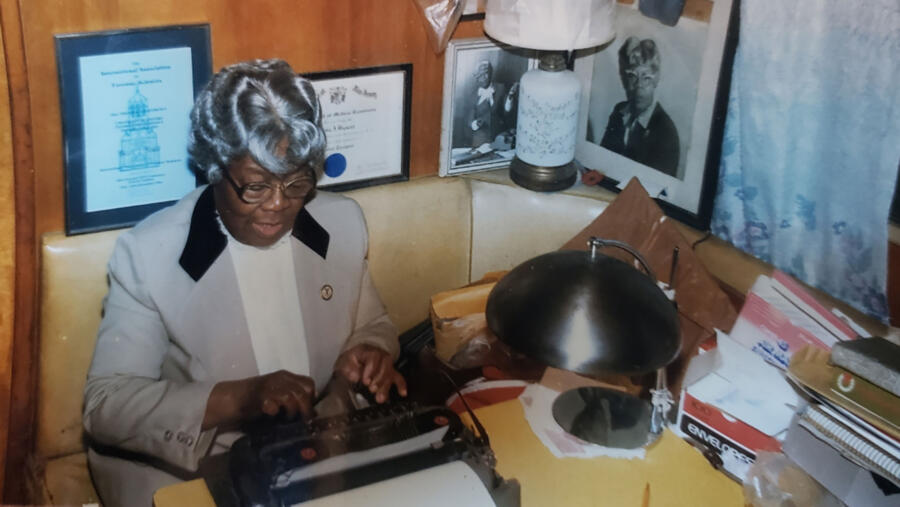

Her grandsons say Blount never made much money, living in a modest one-bedroom trailer stacked with her papers and instruments. She used a typewriter, refusing to own a computer or cell phone. And she worked well into her 80s, her mind always churning to conceive new contraptions like an automatic eye dropper that she put together with plastic, paper clips and rubber bands, Aaron Griffin says.

Blount didn’t charge much for her labor and often worked for free, believing that “once you start charging a lot for something, you let other people own you,” Nicholas Griffin says. She didn’t need material comforts, once bunking down in a jail cell during a work trip to Montana, after making friends with the local sheriff, he says.

What Blount loved the most was to catch people off guard when she was called to testify in court as an expert, defying assumptions about older Black women, her grandsons say.

“She almost kind of welcomed it if you were underestimating her, because that’s where she was going to get you,” Aaron Griffin says.

Nicholas Griffin agrees. “She loved to wow them.”

Related Features:

Frances Glessner Lee: The Mother of Forensic Science