“Rest easy Skylar, you’ll ALWAYS be my best friend,” Shelia Eddy tweeted in 2013 about 16-year-old Skylar Neese. What Eddy failed to reveal to her Twitter followers was that she, along with her best friend Rachel Shoaf, were the ones who stabbed Neese to death after planning the crime in their science class.

Months earlier, the teens had lured their prey to a remote area and killed her.

It happened in 2012. And in 1985. And in 1954.

BFF (Best Friend Forever) killers make a splash in the media. But while they are among the most salacious and fascinating cases, they are not the most common.

“A lot of data says around 30 percent of murders by juveniles have a co-defendant,” Apryl Alexander, associate professor at the Graduate School of Professional Psychology at the University of Denver tells A&E True Crime. “And what we see in those cases are youth bonding over shared problems in their lives: Both peers being socially isolated and not having extended friend groups. Both friends having trouble at home.”

[Watch Kids Behind Bars: Life or Parole in the A&E app.]

The National Institute for Health cites several studies about how exposure to violence at home or in schools and neighborhoods puts teens at high risk for becoming violent themselves. Many criminal psychologists also argue that a teen brain is more malleable, open to a friend’s influence and less developed than an adult’s brain.

“If I don’t have the full cognitive capacity to understand the long-term implications of my actions—it’s not excusing it, but it contributed to the crime,” says Alexander, who has evaluated juvenile defendants before trial.

Beyond poor impulse control, mental health concerns and diagnoses play a role in juvenile crime, says Alexander. In 2020, she received a federal grant from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention to start a trauma treatment program for justice-involved girls.

“Ninety percent of justice-involved girls have a history of trauma,” she says. “So, my question is: What if we knew about their trauma earlier and treated it? Would they be in the criminal legal system?”

Below are five BFF pairs who did end up in the criminal legal system—and where they are today.

Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme

The 1994 movie Heavenly Creatures (starring Melanie Lynskey and Kate Winslet) was based on 16- and 15-year-old friends Pauline Parker and Juliet Hulme, a New Zealand pair who had an elaborate fantasy life—and what their parents considered an unhealthy obsession with each other. (Both girls had been hospitalized for traumatic medical conditions and had no other friends.)

When Parker’s mother Honora told her daughter she couldn’t move away with Hulme in 1954, they used a brick in a stocking to bludgeon her to death. Their insanity plea was rejected.

At the girls’ murder trial, the Crown Prosecutor declared they were “not incurably insane” but “incurably bad.” Parker and Hulme were sentenced to “indefinite imprisonment,” but served just five years. A stipulation of their release was never seeing each other again.

Parker became a librarian and later a children’s horseback riding instructor. Hulme, who changed her name to Anne Perry, is a New York Times bestselling author of historical detective fiction.

In a 2003 interview with The Guardian, Perry asked: “Why can’t I be judged for who I am now, not what I was then?” Perry also said she was kept in a rat-infested solitary confinement cell for three months.

Still, she credits prison with her redemption. “It was there that I went down on my knees and repented,” said the now devout Mormon. “That is how I survived my time while others cracked up. I seemed to be the only one saying, I am guilty, and I am where I should be.”

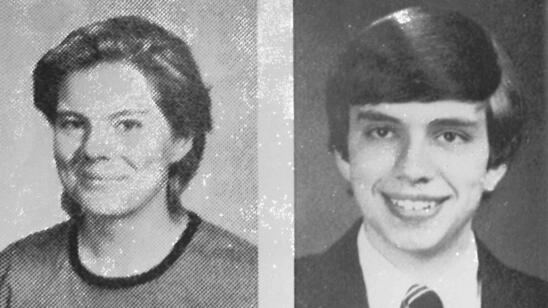

Karen Severson and Laura Doyle

In 1985, California girls Karen Severson and Laura Doyle drowned 17-year-old Michele “Missy” Avila, holding her head down in a shallow stream in Big Tujunga Canyon in Angeles National Forrest over her allegedly sleeping with Doyle’s boyfriend.

The two friends attended Avila’s funeral, comforting her family, even suggesting suspects. They kept up the act for three years.

Convicted at 22, both were sentenced to 15 years to life in an adult prison. Years after the murder, Severson, who’d known Avila since age seven, claimed it was an accident.

“I only wanted to torment Missy,” she said in 2015. After serving 21 and 22 years, respectively, for second-degree murder, Severson and Doyle were given parole.

Doyle has stayed under the radar, while Severson controversially wrote a memoir about the crime. While promoting her e-book, Severson, who sees herself as a reformed bully, seemed to victim-blame Avila: “All this stuff, everything we were accusing her of, she knew she did it, but not one time did she say she’s sorry!”

Shelia Eddy and Rachel Shoaf

Shortly after midnight on July 6, 2012, West Virginia teen Skylar Neese snuck out of her parent’s home to meet her friends Shelia Eddy and Rachel Shoaf.

The group drove to the woods, ostensibly to get high on marijuana; instead, the two killers counted to three and started stabbing Neese, said Shoaf.

In the months after, Shoaf suffered a nervous breakdown. She confessed in January 2013 and brought authorities to Neese’s body. The reason for the killing: “We just didn’t like her,” Shoaf said.

Meanwhile, Eddy continued tweeting normally about TV and hating homework. Later, Eddy was convicted of first-degree murder. For “life with mercy,” she pleaded guilty on January 24, 2014 at the last minute, but did not explain her crime.

Shoaf was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 30 years; she’s up for parole in 2023.

‘The Collie Killers’

In 2006, after an amphetamine-fueled party, two Australian besties from the coal-mining town of Collie, garroted their friend, 15-year-old Eliza Jane Davis, with a speaker wire and buried her under the house. The pair had discussed killing someone before, and one even killed two kittens to prepare herself.

Because they were 16 at the time of the crime, their names were never released. But statements they made to authorities have been made public.

They told police that killing Davis “felt right.” The girls were spiraling before the murder—after losing her mom in a car crash and having a foster care placement fall through, one moved into a flophouse with no electricity; the other struggled with self-harm and abused multiple drugs. That killer’s sister insisted, “I don’t think she would ever have done it without drugs.”

Perth Children’s Court sentenced them to 15 years to life, with one year at a juvenile facility where they had access to each other. Today, they’re both in a women’s correctional facility.

Anissa Weier and Morgan Geyser

In what became known as the Waukesha (Wisconsin) Slender Man stabbing, 12-year old Morgan Geyser stabbed her friend, Payton Leutner, also 12, in the woods. Anissa Weier, Geyser’s best friend, had handed her the knife, instructing her to “go ballistic, go crazy.” The sixth graders believed they were directed to kill by Slender Man, a fictional supernatural character and urban legend.

Geyser told police in 2014 she was afraid of what would happen if she didn’t stab Leutner. But she also calmly said she wasn’t sorry: “I thought about it, but then I decided remorse would get me nowhere,” she said in a 2014 20/20 special, “Out of the Woods.”

Weier seemed scared during her interrogation—legally done without a parent’s presence. “I never really understood what it meant to kill somebody until right now,” she said. But against all odds, Leutner didn’t die. Though stabbed 19 times, she dragged herself to a road where a cyclist found her.

During their attempted murder trials, in which both assailants were charged as adults, psychologists argued that the two had undiagnosed mental health issues and a shared delusion—what the French call folie à deux, a madness shared by two. Ultimately, Geyser, who has a family history of schizophrenia, made a deal to plead guilty to attempted first-degree intentional homicide if found not guilty by reason of mental disease or defect. She was sentenced to up to 40 years in a mental institution. An appeals court upheld that decision in 2020.

Weier was found not guilty of attempted second-degree intentional homicide by reason of mental disease or defect. She was sentenced to up to 25 years in Winnebago Mental Health Institute and released at age 19 in 2021. Weier argued she could only continue to improve her mental health if she was a member of society.

Weier wears a GPS ankle monitor and cannot contact Leutner until 2039. In 2019, Leutner seemed resigned to the fact that her former friends would be released eventually: “If they ever come near me, they’re going right back in. When they get out, I don’t think it’s going to change my life at all.”

Related Features:

Murders By Two: Notorious Examples of Folie à Deux

Why Are There More Serial Killers in the U.S. Than Any Other Country?

What Life Is Like for the ‘Criminally Insane’ at a Maximum-Security Psychiatric Hospital