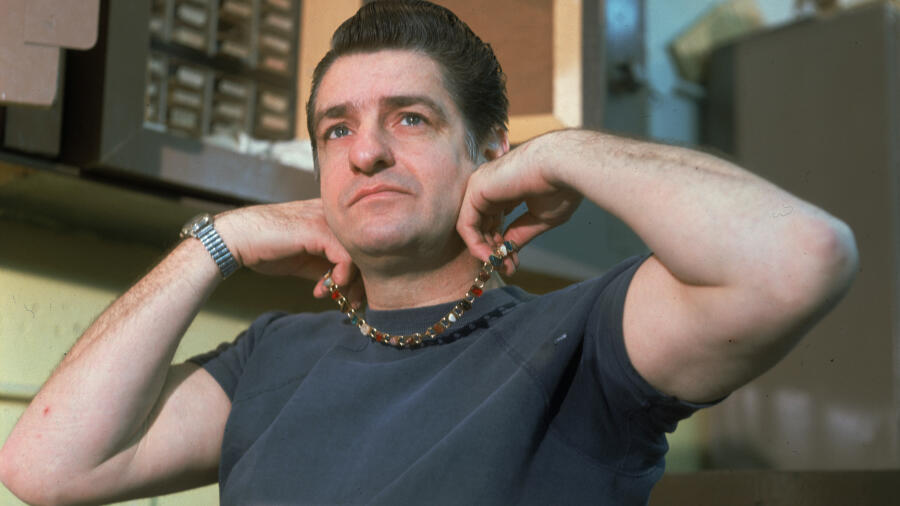

Albert DeSalvo, believed to be the serial killer responsible for the deaths of more than a dozen women in the Boston area in the early 1960s, told of a childhood marked by extreme violence and cruelty.

By his own account, he was the victim of vicious beatings perpetrated by his father, an alcoholic who also brutalized his wife and had sex with prostitutes in front of his children.

So could that explain DeSalvo’s later killings? Possibly, some experts say.

Retired Radford University organizational psychology professor Michael Aamodt tells A&E True Crime that most serial killers come from dysfunctional families, and often have parents who abused alcohol or drugs.

[Watch The Boston Strangler on A&E Crime Central.]

One hypothesis might be that DeSalvo’s father was a psychopath, a biological condition that could have been inherited by DeSalvo, Octavio Choi, forensic psychiatrist and clinical associate professor of psychiatry at Stanford University, tells A&E True Crime.

“The fact that the father behaved in these ways lends some credence to that theory,” Choi says. “[The father’s behavior] models [the idea] that aggression is a valid way of getting your ends met.”

Skepticism Around DeSalvo’s Guilt

Nicknamed the “Boston Strangler,” DeSalvo was arrested in late 1964 and charged with several counts of assault, burglary and sex offenses. He then confessed to killing 13 women from 1962 to 1964. Most of the victims, who ranged in age from 19 to 85, were raped and strangled with stockings.

DeSalvo was convicted of the lesser crimes in 1967, with a sentence of life in prison, but he was never charged with the murders. Although he knew details of the killings, there was a lack of evidence. There was also some skepticism, remaining to this day among some, that he was the culprit. He died at age 42 in 1973 after being stabbed in his cell at Walpole State Prison (now known as Massachusetts Correctional Institution).

In 2013, DNA from DeSalvo’s nephew showed a 99.99 percent familial match with DNA found on the Boston Strangler’s last victim, Mary Sullivan, which led authorities to conclude DeSalvo likely was responsible for the other 12 murders as well.

Albert DeSalvo’s Early Years

DeSalvo was born in 1931 and grew up with five siblings in the small city of Chelsea, Massachusetts. He started getting into trouble in his youth and was sent twice to the Lyman School for Boys in Massachusetts, a reform school. He joined the U.S. Army at 17 and served for eight years, during which time he married a German woman, Irmgard Beck, and had two children.

Author Gerold Frank wrote about DeSalvo in the 1966 book, The Boston Strangler, drawing from hundreds of hours of personal interviews as well as court, medical and police documents.

In the book, DeSalvo described how he and his brother had to stand in front of their father, every night, to be beaten with a belt “with a big buckle on it.”

“I saw my father knock my mother’s teeth out and then break every one of her fingers. I must have been seven. Ma was laid out under the sink—I watched it,” DeSalvo said. “He smashed me once across the back with a pipe. I just didn’t move fast enough.”

DeSalvo recounted that his father once sold him and two of his sisters for $9 to a farmer in Maine, unbeknownst to their mother, who searched for them for six months, Frank wrote in the book.

DeSalvo also told grim stories about his early life to Ruth Brown, a New York woman who wrote to him after reading The Boston Strangler and once visited him in prison. Brown told the Elmira, New York newspaper, the Star-Gazette, that his mother and sister used to tell him they wished he were dead. “He said when he was a little boy, he slept with a dog because a dog wouldn’t bite him,” Brown was quoted.

Did an Abusive Childhood Turn DeSalvo Into a Serial Killer?

According to “The Incidence of Child Abuse in Serial Killers,” a study of 50 serial killers co-authored by Aamodt, 68 percent of serial killers suffered some type of maltreatment, 36 percent suffered physical abuse, 26 percent suffered sexual abuse and 50 percent suffered psychological abuse. The latter was the most glaring difference with the general population, where only 2 percent of people suffer from psychological abuse, according to the study published in 2005 in the Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology.

However, an abusive childhood alone typically isn’t enough to yield a serial killer, Aamodt cautions.

“I think of it as kind of a point system,” he says. “If you go through one thing in life—you’re abused, but everything else is pretty stable—it’s not going to have as much effect in terms of you becoming habitually aggressive or violent. But when you are abused and you have neurological damage, from substance abuse or injury, or because you’re exposed to lead, each of those things that happened are building up points.”

Sources don’t mention whether DeSalvo abused substances, although authorities speculated his involvement in a drug prison ring led to his death. It’s also possible DeSalvo suffered from undiagnosed neurological damage, Aamodt and Choi say.

At one point, DeSalvo was diagnosed as having “a sociopathic personality,” Frank writes. At his trial in 1967, a psychiatrist testified that DeSalvo was suffering from “schizophrenia of the paranoid type.”

Choi says “sociopathy” is a term that has been used interchangeably with “psychopathy,” even though the personality disorders have different characteristics.

Psychopaths represent fewer than 1 percent of all adult males, but are estimated to commit 50 percent of all violent crimes, according to data presented by Choi in his lecture, “The Neuroscience of Real-Life Monsters: Psychopaths, CEOs & Politicians.”

Psychopaths have differences in brain structure at an early age leading to a lack of empathy and fear, as well as impaired learning, Choi says in another lecture, “The Criminal Brain.”

Criminal psychopaths, in particular, have severe deficits in emotional reasoning that prevent them from learning there are consequences to hurting others, Choi says.

While psychopathy doesn’t have a strong correlation with childhood abuse, the latter is “bad for brain development,” Choi says. “A lot of people with traumatic brain injury are emotionally blunted.”

As for the notion that DeSalvo was schizophrenic, Choi believes his criminal behavior tends to indicate otherwise. DeSalvo carefully picked his victims’ buildings and conned their way into the women’s apartments, which runs contrary to the fact that schizophrenics generally are socially impaired and have difficulty lying, he says.

Instead, psychopaths generally think rationally and can be “quite capable” at IQ (intelligent quotient) tests, he says.

Indeed, DeSalvo had an IQ of 93, in the normal range. His score was slightly higher than the average IQ for serial killers, which is 92.7, and well above serial killers’ median IQ of 85, Aamodt says.

“The more victims you have,” he says, “the brighter the serial killer.”

Related Features:

Serial Killers Who Were Murdered in Prison