Warning: The following contains disturbing descriptions of violence and sexual violence. Reader discretion is advised.

On Halloween 2005, 25-year-old photographer and Wisconsin resident Teresa Halbach disappeared. Five days later, her family’s worst fears were confirmed when her Toyota RAV4 was found at Avery’s Auto Salvage, in nearby Two Rivers. Halbach’s blood and bone fragments were also found on the property.

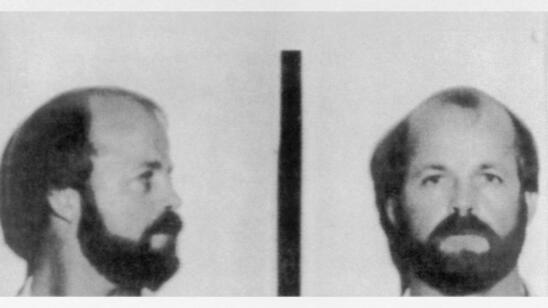

That salvage yard belonged to Steven Avery, 43 at the time, who had just been exonerated of a wrongful sexual assault, attempted murder and false imprisonment conviction 18 years into his prison term, when DNA evidence proved that another convict—Gregory Allen—was guilty of the crime.

But in the case of Halbach, the DNA worked against Avery: His blood was also in the vehicle. More damning still: Avery’s nephew, 16-year-old Brendan Dassey, confessed to police that he and Avery had raped and killed Halbach.

Avery maintained his innocence, suggesting that he was part of an elaborate framing by Manitowoc County law enforcement as retribution for a $36 million civil suit he’d filed against the city for his wrongful imprisonment. His nephew, meanwhile, later recanted his confession, suggesting that he’d been coerced into telling the police what they wanted to hear.

What Happened After Brendan Dassay Recanted His Confession

The jury didn’t buy it. The prosecution used Dassey’s confession as a cornerstone to their case, and both men were convicted—Avery for first-degree intentional homicide and being a felon in possession of a firearm; Dassey for first-degree intentional homicide, mutilation of a corpse and second-degree sexual assault. Both received life sentences.

Halbach’s murder and the subsequent trials served as the premise for a popular 2015 documentary series. After it premiered, hundreds of thousands of viewers petitioned state and federal government to pardon the pair.

The Fight to Exonerate Steven Avery and Brendan Dassey

Both the convicted men have been fighting hard for their release. Avery hired high-profile criminal defense attorney Kathleen Zellner to represent him, who has in turn filed numerous appeals, one in which she claimed there was credible evidence linking Dassey’s brother, Bobby, to the murder. And in June 2017 Brendan Dassey’s conviction was overturned by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit, with U.S. Magistrate William Duffin of Milwaukee arguing that interrogators “repeated false promises” to Dassey about his confession, rendering it involuntary. Six months later a higher court of appeals nullified that decision, meaning Dassey remains incarcerated for life per the jury’s verdict.

But even if Dassey’s confession had been involuntary, that doesn’t address the truth of the case—only the legally permissibility of the evidence. Dassey confessed to a crime. And given that confession, doesn’t it follow that he must’ve done it?

Reasons Why People Confess to Crimes They Never Committed

Not necessarily, says Saul Kassin, distinguished professor of psychology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and an expert in false confessions. Kassin says there are numerous reasons why someone like Dassey might confess to a crime he hadn’t committed, starting with his age.

“People prefer rewards and punishments that are now rather than later,” Kassin says. “That tendency is exacerbated—it’s on steroids—when it comes to juveniles.”

As such, Kassin says that when put into the uncomfortable situation of a police interrogation, juveniles are much more likely to seek the short-term reward of getting out of an interrogation room over the longer-term reward of not going to prison.

“If you look at wrongful-conviction databases, and at the subsample of those wrongfully convicted because they confessed, the proportion of juveniles is disproportionately high.”

In one of the most notable of such instances—the Central Park jogger case—five New York juveniles confessed to brutally raping a female jogger on an April night in 1989. The youth later recanted their confessions. In 2002, serial rapist Matias Reyes confessed he and he alone committed the crime. The DNA that had been found at the scene matched his.

Kassin says low IQ also correlates to false confessions. Dassey’s IQ is around 70, meaning he’s considered “borderline” mentally disabled. According to Kassin, “People who are mentally deficient are generally more vulnerable to influence from others. When you ask them questions they’re more likely to give an affirmative response.”

There’s no way to determine what percentage of confessions are false, as that would require knowing the truth about events beyond what’s been ascertained by the criminal-justice system. However, we can start to infer the prevalence of false confessions by looking at those who were exonerated of their crimes later, and seeing how many of them confessed to crimes to which they were ultimately proven innocent.

The National Registry of Exoneration’s 2017 report on exonerations found approximately 20 percent of that year’s exonerees had confessed, falsely, to their crimes. The Innocence Project, which works to free the wrongfully convicted via DNA testing, has found that in approximately one of four exonerations the wrongfully convicted had falsely confessed.

According to Kassin, “nobody saw that number coming,” when the Innocence Project first began their DNA exoneration work in 1992. And people on juries still have a problem internalizing what that means, Kassin says—namely, that confessions are not foolproof evidence.

People understand that other factors—eyewitness accounts, for example—can contain human error. “Everyone understands fundamentally that people aren’t perfect in their perception or reports,” says Kassin. “[But] there’s an assumption…that nothing you do would get an innocent person to confess.”

Still, just because some confessions are unreliable doesn’t mean when a suspect recants their confession they’re innocent. Guilty parties, too, can crumble under the pressure of an interrogation and think better of it later.

“It doesn’t tell you anything about guilt or innocence,” says Kassin. What would help, he says, is if police forces “mandate the recordings of interrogations, from start to finish. It will enable [juries] to evaluate the degree of coercion.”

Until then, juries continue to convict on the strength of confessions, even when DNA shows evidence that would exonerate a defendant. Such was the case with the Central Park Five, when a rape kit administered to the victim showed that none of the juveniles could be linked to the crime. Juries convicted them anyway.

“It’s considered the gold standard of evidence,” Kassin says. “Confessions create convictions… Nothing else seems to matter.”

Steven Avery and Brendan Dassey Update

On April 12, 2021, Zellner filed a motion in Manitowoc County that alleges Bobby Dassey was seen moving Halbach’s car onto the Avery property. A former newspaper delivery driver in the area signed a sworn affidavit attesting that at the time of Halbach’s disappearance he notified the sheriff’s office about what he witnessed, but was never contacted for more information. Allegedly, he was told by one of the police officers, “We already know who did it.”

Related Features:

What Makes Criminals Blab About Their Crimes?

How to Tell If Someone Is Lying: A Retired Detective Reveals All

A Lawyer Investigates the Depression-Era Child Murders in Her Family