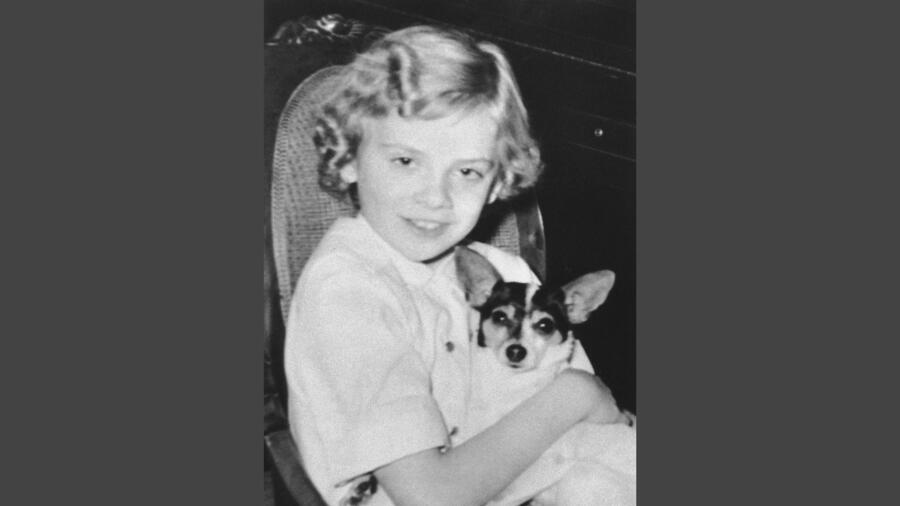

On a Friday evening in early March 1959, 9-year-old Candice Elaine “Candy” Rogers ventured out of her house alone and began going door to door in her Spokane, Washington, neighborhood in hopes of selling mints to raise funds for Camp Fire Girls, a national youth development organization. (It’s now known as Camp Fire.)

But Rogers never returned home to her apartment above a neighborhood grocery store that night. As it got darker outside, her family became increasingly worried and alerted police. Spokane residents joined together with law enforcement agencies to look for Rogers and, after 15 days of searching, they discovered the young girl’s body seven miles from her home, in the woods. She’d been sexually assaulted and strangled to death.

The Spokane police worked to identify Rogers’ killer, but eventually, the case went cold. In November 2021, more than 62 years after her murder, police announced that they’d used DNA evidence from the crime scene and forensic genetic genealogy to link the late John Reigh Hoff to the crime. Though Hoff had died by suicide in 1970, his daughter provided a DNA sample that matched with semen found on Rogers’ clothing. Police confirmed the match after exhuming Hoff’s body.

The murder of Candy Rogers will be the subject of an upcoming episode of Cold Case Files, airing on A&E.

Brittany Wright, a forensic scientist with the Washington State Patrol Crime Laboratory Division who helped solve the case, spoke with A&E True Crime about the impact of Rogers’ murder on the Spokane community—and how advancements in DNA technologies eventually helped law enforcement unravel the mystery of her death.

What was the public response to Candy Rogers’ disappearance?

Within 24 hours, a massive search party formed and all of the Spokane community came together to help look for her—police officers, civilians and local Air Force servicemen searched on motorcycles, by foot, car, horseback and helicopters. The search primarily focused on and around N. Pettet Drive, known in Spokane today as Doomsday Hill, where [some mint boxes that looked like they were tossed by a moving car] were found, but extended miles beyond. The efforts also included a thorough search of the Spokane River.

Part of the search involved the use of helicopters that were manned by Air Force servicemen. One helicopter, carrying five servicemen, hit low-hanging electric wires and crashed into the river, killing three of them.

[Stream episodes of Cold Case Files in the A&E App.]

The community continued to talk about, publish, broadcast and search for Candy with no success for 15 days. On March 21, 1959, two hunters were in the woods near a rock quarry, about five miles from where Candy went missing, and noticed two little girls’ shoes neatly placed on the ground. They let the police know, and when the police returned to the site and searched the brush nearby, they found Candy’s body.

The news hit the community extremely hard and became a significant part of local history.

How did the investigation unfold after that?

The Spokane Police Department formed a large task force to solve the case. The case file eventually became the largest in the department’s history. Police questioned multiple suspicious individuals, but nothing panned out.

One promising lead was the discovery and questioning of Hugh Bion Morse, who was a serial killer and known to prey on younger girls. He was in the Spokane area at the time of Candy’s murder, and he fit much of the profile of the killer’s modus operandi. He was eventually ruled out by DNA evidence in the early 2000s.

The case never entirely disappeared from the community’s memory. Detectives worked on the case tirelessly over the course of 60 years.

What was your personal connection to the case?

Both of my parents were born in Spokane and I was raised in Spokane. They told me about the terrible crime that occurred, and I distinctly remember them warning me to be wary of strangers, to ensure I didn’t befall the same fate as Candy. So this case was a part of my household growing up, 30 to 40 years after it had happened.

What happened during the 2000s with this case and DNA advancements?

In 2001, the lead detective at the time, Mindy Connelly, knew that advances in forensic science, particularly DNA analysis, could be the key to solving the case. She submitted Candy’s clothing to the lab in the hopes that the perpetrator’s DNA could be identified.

Forensic scientists identified semen in Candy’s underwear and developed a DNA profile. The police department uploaded the DNA profile into the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), but it didn’t get any hits. The case never [technically] went cold, with continued efforts by the police who tracked down persons of interest and submitted their DNA for comparison against the profile, but the killer’s identity remained unknown.

The catalyst came around 2017 to 2018, when forensic genetic genealogy hit the scene and police used it to solve the infamous Golden State Killer case. As soon as forensic genetic genealogy gained notoriety, the Spokane Police Department immediately re-assessed their cold cases to see if any of them could be solved this way. They picked Candy’s case and submitted it in 2018 to the crime lab for evaluation, which is when it was assigned to me.

What is forensic genetic genealogy and how does it work?

With forensic genetic genealogy, you can take DNA from a crime scene and run it against an ancestry database. You are asking the database to look at the DNA from your crime scene and see if that person is closely related to anyone in the ancestry database. If you get a hit, you can also tell how closely related the individual may be, such as a first cousin or a second cousin once removed. It is then up to a genealogist using public records, such as birth certificates, wedding certificates and other documents, to try and figure out the identity of the perpetrator. They can do this by tracing back to a common ancestor and then trying to narrow the search down to a single family or even a single name.

This can help law enforcement solve cases in which traditional DNA means haven’t garnered any leads. Not everyone who has committed a crime will be in CODIS, nor will you always have a witness who can tell you who perpetrated the crime. So forensic genetic genealogy is yet another tool in the law enforcement toolbox if traditional means have reached a dead end.

How did you actually solve this case after it was assigned to you in 2018?

I was able to locate a DNA sample that had been stored in the crime lab freezer since 2001. I re-analyzed the sample in order to confirm that it matched the original perpetrator’s DNA profile that was obtained in 2001 and I did a brief diagnostic analysis to determine that it would qualify for forensic genetic genealogy.

The lead detective and I then agreed to send some of the sample to a genealogy lab. The sample arrived in a crushed box; the DNA tube had also been crushed and the DNA had leaked out. The lead detective and I were absolutely devastated.

Then, we attempted to send a little bit more of the DNA to the company and this sample arrived in good condition. Unfortunately, they considered the DNA sample to be too degraded for their lab technology and they could not read any genetic information from the DNA.

Finally, after a year or so of thinking that even forensic genetic genealogy wouldn’t be able to solve Candy’s case, I heard of a lab in Texas called Othram that could handle these fragile, degraded DNA samples. I contacted them to see if Candy’s case could qualify. Once they confirmed it could, I sent off another small amount of the DNA sample—which had, by this time, whittled down to the very last drops of it, so to speak—and sent it off for testing. It took this lab six months to run the DNA and the ancestry and come back with the three Hoff brothers as the possible perpetrators.

Who was Candy’s killer, John Reigh Hoff?

Not a lot is known about John Hoff, as he lived a fairly uneventful life and died early by suicide at the age of 30. He was born in 1938 and briefly served in the Army before being kicked out after being arrested for attempted rape of a woman in Spokane. What the Spokane Police Department eventually confirmed is that he lived in the same neighborhood as Candy and may have decided, on a whim, to take her that night.

What did solving this case mean to you, both personally and professionally?

I consider this to be the highest achievement of my forensic career. As a forensic scientist, this case had so many hurdles to overcome and so many technical puzzles that required thinking outside of the box and persistence. This was the ultimate forensic puzzle to piece together. The main takeaway that will always stick with me is that persistence and the ability to find a way around any brick wall you encounter will eventually lead you to an answer. To never give up, even when it seemed hopeless at times; to know that there may be another huge break in DNA technology just around the corner that could be the pivotal shift needed for any case to be solved; and to never let any case stay on a shelf for too long before looking at it again.

Why do police continue to try to solve cold cases, even when decades have passed?

No matter how old a case is, law enforcement still views it as significant as a current case. The victim still needs justice and the victim’s family—no matter how old or how few are left alive—still deserves answers. And just as importantly, law enforcement works on these cases to help allow the community to heal as well.

Related Features:

The Murder of Megan Kanka: Why Megan’s Law Was Created

‘Candy Man’ Serial Killer Dean Corll: Renewed Search for Victims After Nearly 50 Years

Ashley Freeman and Lauria Bible: The Mysterious Murders of Teenage Best Friends