In 1971, Edgar Smith became a free man after spending more than 14 years on death row in New Jersey for the 1957 murder of 15-year-old Victoria Zielinski, who was bludgeoned to death with rocks and a baseball bat.

Smith, the longest-serving death row prisoner at the time, waged a persistent campaign declaring his innocence, filing 19 appeals and writing from jail the book Brief Against Death.

He’d gained national notoriety thanks to his friendship with William F. Buckley Jr., the conservative columnist and founder of National Review magazine, who became convinced of his innocence.

The two got to know each other after Buckley, 36 at the time, read a 1962 article about Smith in New Jersey’s Ridgewood Herald-News that mentioned Smith read National Review, author Sarah Weinman writes in her book, Scoundrel: How a Convicted Murderer Persuaded the Women Who Loved Him, the Conservative Establishment and the Courts to Set Him Free.

[Stream episodes of 60 Days In in the A&E App.]

Buckley wrote to Smith to thank him and to offer him a lifetime subscription to the magazine. Eventually, they began to correspond, exchanging hundreds of letters over the years; by 1964, Buckley had set up the basis of a legal defense fund for Smith, Weinman writes in her book.

In 1965, after visiting Smith in prison, Buckley wrote an article in Esquire raising questions about Smith’s conviction and his “inherently implausible” case.

Smith’s conviction was vacated on his 19th appeal after he claimed his confession was coerced. The move came in the wake of Supreme Court rulings that established that incriminating statements cannot be admitted into evidence unless the suspects were informed of their rights before making those statements Weinman explains in her book.

Smith got a new trial in 1971 and was released from prison after pleading “non vult,” or no contest, to killing Zielinski. He was sentenced to 25 to 30 years, but the judge credited 14 years in time served, more for good behavior and suspended the more than four years remaining, the book says.

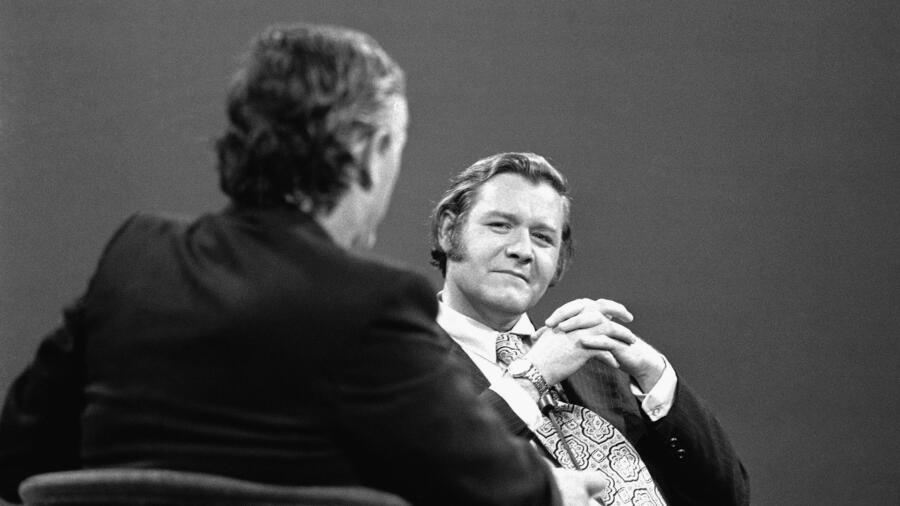

Smith walked out of prison and was picked up by two limousines: one for him and Buckley, one for family, friends and lawyers, according to the book. They went straight to a taping of Firing Line that aired in two episodes, where Smith maintained his innocence, as he did for the next five years.

Smith became a sought-after pundit on all things prison, Weinman says, with speaking engagements, talk show appearances and op-ed writings.

He got married again—his first wife, with whom he had a daughter, divorced him while he was in prison—and moved to California, where his fortunes dwindled, the book says.

In 1976, Smith abducted and stabbed Lefteriya Lisa Ozbun in San Diego. Ozbun escaped and testified against him at trial. During the trial, he admitted to killing Zielinski, an acquaintance of his, when he was 23.

“For the first time in my life, I recognized that the devil I had been looking at the last 43 years was me,” he said. “I recognized what I am, and I admitted it.”

So how did Smith, who died in prison at 83 in 2017, manage to persuade Buckley, and so many others, of his innocence?

Put simply, with his intelligence, Louis B. Schlesinger, a professor of psychology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, tells A&E True Crime.

“Very often people equate high IQ with lack of dangerousness—and that’s not true,” Schlesinger says. “Even Buckley, one of the smartest men in the world, advocated on behalf of Smith to get him released. It was because [Buckley thought] someone of this intelligence couldn’t have done it.”

In person, Smith was taciturn and awkward. But in writing, he was eloquent and compelling, Weinman tells A&E True Crime. She described Smith’s Brief Against Death as a “competently written book.”

“It is a persuasive document. Even if you know all the facts as I did, I found myself being sucked into Edgar’s world view,” she says.

Weinman also points to the correspondence between Smith and Buckley, and between Smith and his book editor Sophie Wilkins, whom he seduced with his letters. “I really do understand how Sophie and Buckley were sort of caught in this net, because Edgar was a very good manipulator, and he used his writing to persuade,” she says.

Among those who did legal research for Smith was 24-year-old law student Jack Carley, who grew up in Bergen County, New Jersey, and was in Buckley’s circle. Carley tells A&E True Crime that his focus was whether Smith had been deprived of his constitutional rights and unlawfully convicted.

In a conversation following Smith’s second arrest and conviction, Buckley “lamented that we had been had,” Carley recalls.

“I remember saying to [Buckley], ‘The system didn’t work and we had a duty to correct the system. I don’t think we have anything to apologize for,'” Carley says. “Both of us felt a certain amount of guilt and shame that we had believed in Edgar.”

“We made a mistake,” he adds, “and I think it was a mistake of the heart, more than of the head.”

According to a New York Times review of Weinman’s book, Buckley “trusted and gave a national platform to a man he perceived to be like himself,” meaning white, male, straight, conservative and financially secure.

Carley objects to that. “This person came to Bill [Buckley]’s attention as being on death row the longest at that time. I don’t think the fact that he was white ever entered his mind,” he says. “Bill did what he did in the service of a cause,” he says.

In the introduction to her book, Weinman makes the point that, particularly in the current age of mass incarceration of Black and brown people, “the transformation of Edgar Smith into a national cause more than half a century ago raises uncomfortable questions about who merits such a spotlight and who does not.”

Ironically, it was Buckley who called the FBI to tell them where to find Smith. On the run for two weeks after attacking Ozbun, Smith called Buckley’s office and spoke with his executive secretary, who relayed the message to Buckley, Weinman writes.

Once Smith’s “wrongful exoneration” came to light and he was jailed again, the relationship between him and Buckley didn’t get public scrutiny in the following years and decades, Weinman says.

Why was that?

“Even after writing Scoundrel, I still grapple with this,” Weinman says. “What I land on is that it’s because, after everything happened, Buckley wrote one piece for Life magazine summing everything up, and then never spoke about it again. He never discussed it again.”

Related Features:

Ellen Greenberg’s Mysterious Death: Could Someone Be Capable of Stabbing Themselves 20 Times?

Did Roger Coleman Really Believe He was Innocent of Murder?

The Staircase Murder of Kathleen Peterson: What Really Caused Her Death?