In the book, The Serial Killer’s Apprentice, Katherine Ramsland and Tracy Ullman explore the story of Elmer Wayne Henley, Jr., who was a teenager when he helped serial killer Dean Corll lure his young victims.

Corll raped, tortured and murdered at least 27 young men between 1970 and 1973 in the Houston, Texas area. He was shot and killed by Henley in 1973.

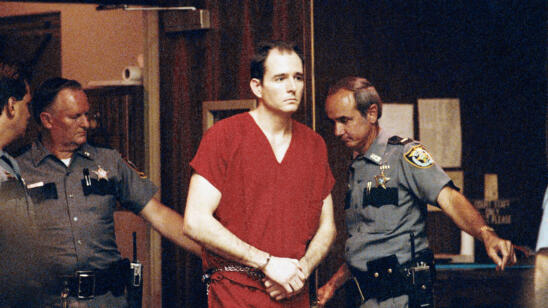

Henley was convicted in the murders of six young men and is serving six consecutive life sentences in a Texas prison. (Corll had another teenage accomplice, David Brooks, who was convicted of murder with malice, sentenced to life in prison and died in 2020.)

The Serial Killer’s Apprentice also delves into how predators exploit young people in light of current neuroscience about teenage vulnerability. Ramsland, a professor of forensic psychology at DeSales University, speaks with A&E True Crime about her phone conversations with Henley, whom she refers to as “Wayne,” and how he views his actions.

What is Henley like?

He is a reader, kind of self-educated, articulate and soft spoken. He was intrigued with my psychology background, and I approached him more as an academic than a media person. His feeling was that his story had never been fairly told, but he didn’t want to say anything that would mitigate his sense of responsibility.

The original books about these crimes were based on police reports, and the police reports were deficient. I have them, and there are a lot of gaps and distortions in what they wrote down in those early days.

What kind of conversations did you have with Henley?

Initially this was about telling his story, but then it became more about him probing into his own sense of himself. It became about me listening, to help him work through stuff. I introduced new ideas to him, like that of the ‘temporary psychopath,’ or accomplices who get pulled in by adult predators and who do things that are uncharacteristic of them while they are under the influence of the adult. He resisted that concept for a while, then he began to think about it and consider how it might apply to him. And as he was doing that, it was taking him to dark places.

He was having terrible dreams, it really affected him. I have training in dream therapy and dream interpretation, so I thought, ‘Let’s work through these.’

How does Henley explain falling into Corll’s trap and becoming his helper?

The way he says it, he needed money and Corll was offering $200 per boy to sell them to a trafficking network where they ended up as pool boys in California.

Henley was 15 and was working part-time at a gas station to help his family. His father had left and was paying no child support; he had three younger brothers and his mother was not working, and $200 in 1973 was a lot of money. So finally, he said to Corll, ‘OK, I will help.’

The first time, he picked up a hitchhiker, whose identity is still not known. Then Corll said to him, ‘[The people in the trafficking network] murdered him, and now you’re implicated. If you don’t do what I say, you’re going to prison.’ Corll, the predator, knew exactly how to manipulate people.

How does Henley talk about killing?

With great horror—and he doesn’t like talking about any of it. The first victim he killed was Mark Scott when [Wayne] was 16. Corll told him he had to strangle him, but he couldn’t do it, he didn’t have the strength. So Corll had to help him finish the job.

At the time, Wayne thought God would strike him dead. He had wanted to be a minister and read the Bible every day, so when [God striking him dead] didn’t happen, he started to question, and his whole world was shifted. Corll had constant criticism of God and religion and faith, to get Henley to be a proper accomplice.

What made Henley pick up a gun and shoot Corll?

He brought a couple friends [to Corll’s place] one night in August 1973. They were drinking and huffing acrylic paint [to get high]—that’s what kids did in those days—and they all passed out. When they woke up, Corll had bound them and said he would sexually assault and kill them. Corll said Wayne had to undress the female and assault her while he was going to work on the boy.

Wayne had been raised in a household with a mother and grandmother, and he’d been raised to always protect women. He felt responsible for the girl. She was bound, and he was cutting her clothes off, and she kept saying, ‘There’s no way you’re going to let something happen to me.’

Corll had laid the gun down, so Wayne picked it up. Corll came at him and Wayne shot him. Corll had taught him to shoot, and keep shooting, until the target is down, so Corll was caught in his own mechanism. After Wayne shot Corll, he could have said nothing about the other bodies. He could have said he saved the two kids and could have walked away a hero. Instead, the first thing he said when he got into the police car was, ‘There is this boat stall where I think [Corll] has some bodies.’ He wanted the families to get those kids back.

You’ve written, ghostwritten or coauthored 70 books, several about serial killers. What sparked your interest in this topic?

Probably the fact that when I was a kid, there was a serial killer in my area, John Norman Collins [who was convicted of murdering Karen Sue Beineman in 1969 and suspected of killing seven more women]. I started having contact with him, I think in 1997, after I just decided to write to him. I wasn’t even in the field of forensics at the time, but I was sort of haunted by him. We had a long correspondence.

Has writing about serial killers ever affected you negatively?

It’s more clinical for me. I am a researcher. It hasn’t really affected me…or if it has, I don’t know it. I have friends who are a support network: We talk about all this stuff and I think that helps a lot.

Related Features:

‘Candy Man’ Serial Killer Dean Corll: Renewed Search for Victims After Nearly 50 Years

Was Caril Ann Fugate Really Charlie Starkweather’s Murderous Accomplice?