The following contains disturbing descriptions of violence. Viewer discretion is advised.

Griselda Blanco built a reputation of killing first and asking questions later.

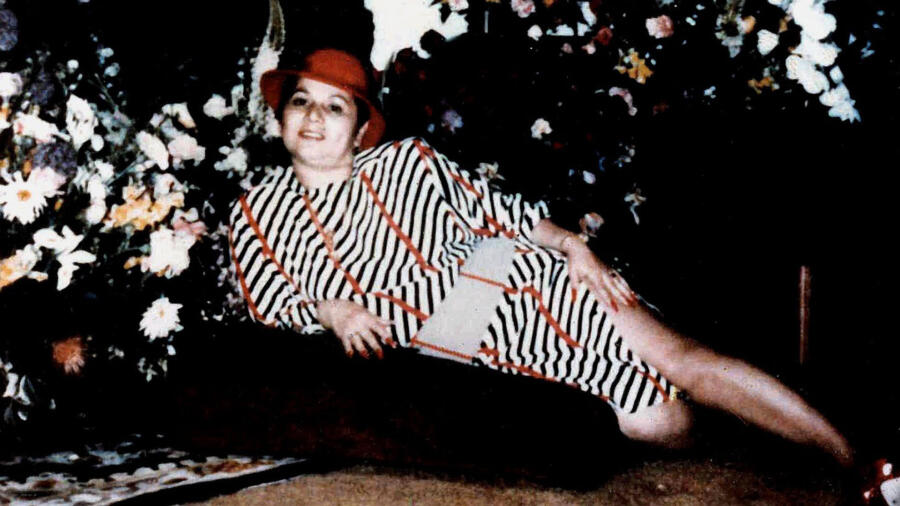

Dubbed the “Cocaine Godmother,” the former Colombian drug lord left Miami’s streets awash in blood during southern Florida’s drug wars of the 1980s. Blanco first made her name as a trafficker in the 1970s and later became a major player in Miami, distributing around 300 kilos (more than 660 pounds) of cocaine a month. To protect her vast empire and eliminate the competition, she reigned with terror—allegedly responsible for more than 200 murders, including the assassination of all three of her husbands—while amassing more than $2 billion in wealth.

Before she became a high-level operative with the infamous Medellin cartel and one of the world’s richest cocaine kingpins, Blanco lived in poverty, surviving as a pickpocket and prostitute on the streets of Colombia.

From Rags to Ruthless Riches

Blanco’s life of crime began in childhood. Born in 1943, Blanco moved with her mother, a prostitute, to Medellin, Colombia when she was around three years old. She was often beaten and endured years of sexual assault at the hands of her mother’s clients. The cycle of violence and abuse led Blanco to roam the streets, where she engaged in prostitution at a young age. She eventually left home and never returned.

At the time, Medellin was considered the most dangerous city in the world and epicenter of the coke trade. Blanco became friendly with low-level criminals and resorted to petty offenses to stay alive.

“From the very beginning, Blanco’s crimes were looting and smuggling. At first it wasn’t [smuggling] cocaine. It was perfume from Venezuela,” Aldona Bialowas Pobutsky, a professor at Oakland University and author of Pablo Escobar and Colombian Narcoculture, tells A&E True Crime.

At age 11, Blanco allegedly helped kidnap a 10-year-old boy. When the boy’s parents refused to pay a ransom, she shot and killed him. Several years later, she married her first husband, Carlos Trujillo, a forger of immigration papers. They had three sons together, Osvaldo, Uber and Dixon, but the marriage fell apart. It is believed Blanco had Trujillo murdered in 1970.

Blanco’s first foray into big crime came when she met her second husband, a drug trafficker named Albert Bravo. They moved to New York in the early 1970s and began smuggling cocaine into the United States. In a 1989 interview, Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agent Steve Georges told the Sun-Sentinel that Blanco “was the first to use multiple sources of supply so that she could always keep the cocaine pipeline full.” She also advocated for “pooling trafficker resources and sharing the risks.” Her business model gave rise to the modern-day cartel.

Blanco’s Queens-based enterprise exploded overnight, cutting into a sizeable share of the drug market previously cornered by the Italian mafia. This attracted the attention of law enforcement and federal agents. “She was bringing in cocaine secreted in undergarments, bras and girdles; in just anything that could carry cocaine and be brought into the country,” Bob Palombo, a former DEA agent who helped take Blanco down, tells A&E True Crime. “She was a tremendous businesswoman in her own right.”

During a joint New York Police Department/DEA sting called “Operation Banshee,” authorities intercepted 150 kilos (330 pounds) of cocaine meant for distribution by Blanco and Bravo. They indicted the couple, along with dozens of their henchmen, in April 1975 on federal drug conspiracy charges, but the duo fled to Colombia before being apprehended.

Later that year, Blanco suspected Bravo had stolen money out of the business and killed him in a shootout. His death earned her another nickname: the “Black Widow.” With Bravo out of the picture, Blanco was in full control of the enterprise—free to rule as she saw fit.

Blanco Brings Heat to Miami

For several years, Blanco continued running the business from Colombia. At one point, she allegedly smuggled cocaine into the U.S. on a ship named Gloria—a vessel the Colombian government had sent to take part in America’s bicentennial celebration in New York harbor. In 1978, she married Dario Sepulveda, a known bank robber, and gave birth to her fourth son, Michael Corleone Blanco, whom she named after Al Pacino’s character in The Godfather. Blanco returned to the U.S. in the late 1970s, establishing a new operation in Miami. Miami had been a popular winter vacation destination for families and aging snowbirds, but cocaine changed the city’s landscape. “A combination of factors came together in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s that made Miami sort of unique. One of those was the explosion of the cocaine trade and the transformation of the ’70s marijuana era into the ’80s cocaine era,” says Jeff Leen, co-author of Kings of Cocaine and a former Miami Herald investigative reporter who helped expose the inner workings of the Medellin cartel. “It played out with a bunch of rivalry between Colombian gangsters and Cuban-American gangsters on the streets of Miami.”

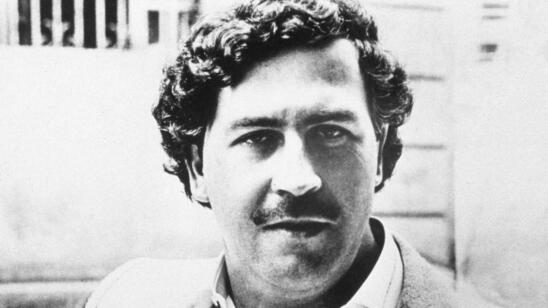

Blanco played a key role in the transformation. Netting around $80 million a month, she lived a lavish lifestyle, owning a collection of luxury vehicles, several mansions and a private jet. She threw hedonistic parties, attended by other bigwigs in the drug trade: a young Pablo Escobar, Carlos Lehder and the Ochoa brothers. But murder became her favorite pastime.

A Blood-Thirsty Queen Among the Cocaine Cowboys

In the 1970s and ‘80s, the narco underworld was dominated by men. Blanco, who stood only five feet tall, was the exception. She sought to eliminate her competition and turned the streets of Miami into a bloody battleground, an era now known as the “Cocaine Cowboy Wars.” Blanco surrounded herself with a group of henchmen known as los Pistoleros, and the bodies began piling up. She ordered countless hits, which her men often carried out in “war wagons” (heavily armored vans with gun ports cut into the sides) and on motorbikes.

“Other criminals killed with intent. They would check before they killed. Blanco would kill first, and then say, ‘Well, he was innocent. That’s too bad, but he’s dead now,'” says Pobutsky. “Blanco turned out to be tough and vicious, and she really used her viciousness to measure up to the men. She did horrible stuff: decapitations, cutting people into pieces, throwing them on the side of the road. Drug kingpins and their associates were afraid of her precisely because of her toughness.”

Blanco had those who owed her money assassinated, and if she didn’t feel like repaying a debt, she’d have the creditor taken out. Innocent bystanders were often caught in the crossfire. In 1981 alone, there were 621 murders in Miami. “People described it as a Wild West situation. They didn’t have enough space in the morgue, so they brought in refrigerator trucks to store the bodies,” Leen explains.

Former assistant U.S. attorney Stephen Schlessinger, who prosecuted Blanco, told the Miami Herald in 2012 that he didn’t “dare venture to guess how many murders she ordered.” Officials suspect she was involved in at least 200 murders, both in Colombia and the U.S., but that number could be much higher. Blanco later had Sepulveda killed after he fled the United States with their son.

Over time, Blanco became addicted to bazooka, an unrefined smokable form of cocaine. “The bazooka, coupled with her homicidal tendencies and increasing paranoia, meant she was bad for business,” says Palombo. Other drug kingpins put targets on her head. Fearing for her life, she moved to California.

A Violent Ending to a Violent Life

On February 17, 1985, Palombo and fellow DEA agents arrested Blanco at her home in Irvine, California. In addition to the drug charges, Blanco pleaded guilty to three murders. She struck a deal with prosecutors and served only 15 years in prison. She was released in 2004 and deported to Colombia.

Blanco lived her final years in anonymity in southwest Medellin. In 2012, at the age of 69, the former Godmother was gunned down outside of a butcher shop by an assassin on a motorbike. “She had so many people eliminated that there are many suspects,” says Leen.

Although Palombo says he doesn’t like to speculate without evidence, his theory is Blanco gave up information after her son, Michael, was arrested on drug charges. “Michael didn’t have much in a way of making a deal to help himself,” says Palombo. “I strongly believe that she intervened for him, possibly giving information to law enforcement. It’s hard to keep something like that a secret, and the damage would have been tremendous to those still involved in the trade.”

While Blanco and Pablo Escobar were bitter enemies in life, in death her final resting place is only 120 steps from his grave at Cemeterio Jardines Montesacro in Itagüí, Colombia.

Related Features:

Who Really Killed Pablo Escobar?

Meet the DEA Special Agents Who Helped Bring Down Pablo Escobar

Why Mexican Drug Cartels Leave ‘Calling Cards’ With Their Murder Victims