The following content contains disturbing accounts of violence. Discretion is advised.

Michael Gargiulo, a California serial killer dubbed by prosecutors “The Boy Next Door Killer,” because he lived near the three women he is known to have savagely slain or assaulted, might have gained notoriety for any of his crimes.

It was one, though, that turned him into a media sensation.

On a night in February 2001, Gargiulo went to the home of Ashley Ellerin, 22, a fashion student he had helped out with a few odd jobs, and stabbed her 47 times. Years later, a detective testified that one wound he inflicted was so forceful it penetrated Ellerin’s skull and took out a chunk “like a puzzle piece.”

On the night she was killed, Ellerin had a casual date planned with actor Ashton Kutcher, whose career was on the rise due to his role in the sitcom “That ’70s Show” and the 2000 comedy film “Dude, Where’s My Car?”

Nearly two decades later, Kutcher—a literal star witness—spoke in a Los Angeles courtroom about peering into Ellerin’s window that evening, after she failed to answer his knocks on the door. He saw what he assumed to be red wine stains on the bungalow floor, he said, but they provoked no alarm. He had mingled with people drinking at a party there a week before.

“At this point, I pretty well assumed she had left for the night, and that I was late, and she was upset,” Kutcher said at Gargiulo’s trial in May 2019. A roommate discovered Ellerin’s body the next day.

‘A Fusion of Sexuality and Aggression’

While lawyers had one nickname for the sadistic murderer, news outlets created another, with allusions to a legendary figure of the 19th century. They called Gargiulo the “Hollywood Ripper,” because of the astonishing aggression apparent in his crimes.

“Whenever there’s more violence visited upon a body than is necessary to kill the person, we call that ‘overkill,'” says Dr. Reid Meloy, a forensic psychologist and clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego. Homicidal fury at this level often involves “a fusion” of sexuality and aggression, says Dr. Meloy, who also consults for the FBI.

“‘Overkill’ typically implies that the individual is feeling rage at the time that they’re doing the act. And then secondly, the knife may be sexualized… Serial murderers themselves have talked about the sexual arousal that’s happening at the moment of these multiple stabbings. And typically, that’s why you will see this literal butchering of the victim.”

Formal Sentencing Still on Hold

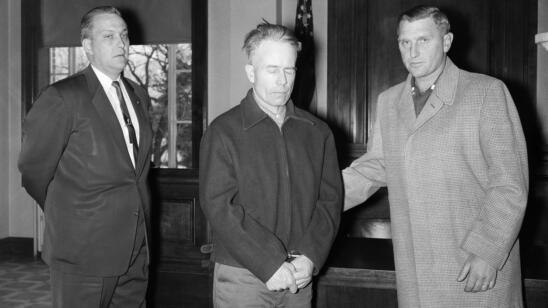

As of April 2, 2020, Gargiulo, 44, is incarcerated in a Los Angeles jail. He has been found guilty of two counts of first-degree murder and one count of premeditated attempted murder.

A jury last autumn recommended he receive the death penalty, on which there is a moratorium in California. But formal sentencing is indefinitely delayed while his defense seeks a new trial, on grounds that investigators failed to turn over critical evidence concerning one witness.

Once that is resolved, Gargiulo is expected to be extradited to Illinois, to face a first-degree murder charge for what prosecutors believe was his first crime, the 1993 death of neighbor Tricia Pacaccio, 18, the sister of a friend. Illinois authorities in 2011 charged him with that slaying.

Gargiulo had fled Illinois for Los Angeles in 1998, to avoid the scrutiny of Cook County police eyeing him in the death of Pacaccio, who was preparing to study engineering at Purdue University.

First, Gargiulo Stalked His Victims

Gargiulo ambushed women when they were alone and stabbed them to death, usually after stalking them for some time. In Ellerin’s case, he had previously helped her change a flat tire, and once repaired a broken heater in her home. His kills were also characterized by an unusually lengthy span, or “latency period,” between them.

Gargiulo’s second known murder came in 2005, when he stabbed to death neighbor Maria Bruno, 32, a mother of four, at her home in El Monte, California.

Bruno was killed in her bed; her body, with 17 stab wounds, was discovered by her estranged husband, Irving Bruno. He told the 911 dispatcher that Bruno’s breast implants had been slashed off, and one nipple was placed over her mouth.

Gargiulo’s attempt at a third killing in California proved his undoing. In April 2008, he broke into the Santa Monica home of Michelle Murphy, then 26. At the time, Gargiulo was living in an apartment just across an alley from her.

Murphy, his lone surviving victim, said she was startled awake by a man hovering over her, stabbing her with a serrated knife. She remembers asking: “Why are you doing this?” Murphy would testify that as she fought back, Gargiulo said “I’m sorry,” and then fled.

This time, he had cut himself during the attack, and blood matching his DNA was found at the scene. He was arrested by Santa Monica police a little more than a month later.

Killer Led Two Different Lives

By most accounts, Gargiulo lived within the parameters of “normal” society throughout his adult life. He had jobs—and, for a time, a family. Little is known about his wife, but he had two children. A son, 16, spoke at a pre-sentencing hearing last year, seeking mercy for his father: “I don’t see a psychopath. I don’t see a murderer. All I see is (my) father.”

It’s not unusual for a cold-blooded killer to live two parallel, but shockingly different lives, says forensic psychologist Meloy, who has not evaluated Gargiulo.

“This aligns with what we know about serial murderers,” he says. “Their targets may be acquaintances or strangers, but they rarely will kill an intimate partner, even if they have that consensually intimate partner during the time that they’re killing.”

He added: “There have been murderers that have said any kind of attachment gets in the way. They do not want to target a woman that they have any kind of emotional connection to, because of the risk any kind of empathy would get in the way of their desire to kill.”

Related Features:

The Blue-Collar Jobs of Serial Killers

Serial Killers Plague Almost All Cities

Why Are There More Serial Killers in the U.S. Than in Any Other Country?

How Rodney Alcala, ‘The Dating Game Killer,’ Used Photography to Lure Victims