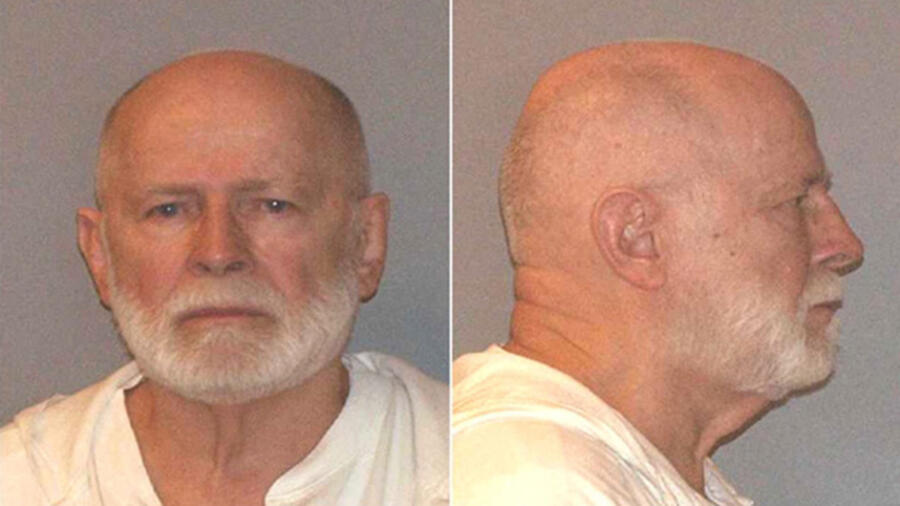

Boston gangster James “Whitey” Bulger Jr. lived by the sword and died by the sword. The question today, more than a year after his gruesome murder in a West Virginia prison, is whether his killer or killers will ever be brought to justice.

A notorious mob boss serving a life sentence for his part in 11 slayings, Bulger, 89, was ailing and confined to a wheelchair on October 30, 2018, when he was slain at the U.S. Penitentiary Hazelton, a high-security federal facility referred to by inmates as “Misery Mountain.”

Bulger is believed to have been beaten by fellow convicts, using a padlock wrapped in a sock as their primary weapon. The Boston Globe reported that two inmates—one, a mafia hitman with a well-known distaste for “rats,” or snitches—were captured on video entering Bulger’s cell the morning of the assault.

Bulger’s murder marked the third death of a prisoner at Hazelton in a matter of months. He had been moved there from a federal transfer center in Oklahoma City less than 24 hours earlier.

So far, no one has been charged in the attack. Officially, the FBI is still investigating Bulger’s death as a homicide, the Globe has reported. Bulger’s family has taken the first steps in seeking financial restitution from the Department of Justice, arguing he was intentionally placed in harm’s way.

Two aspects of the attack on Bulger remain murky, says Shelley Murphy, a Boston Globe reporter who covered Bulger for decades and is co-author of “Whitey Bulger: America’s Most Wanted Gangster and the Manhunt That Brought Him to Justice.”

First is an unusual transfer between federal facilities, away from one better equipped to tend to his medical needs.

Bulger had survived a series of heart attacks while incarcerated. But authorities upgraded his medical condition, indicating that his health had improved. The medical upgrade paved the way for the move to Hazelton, a “lower-level facility” for medical care capabilities.

No one has clearly explained what prompted the health condition upgrade.

Then, there’s the question of why Bulger wasn’t kept at a prison considered more of a safe haven for informants, such as the Coleman II penitentiary in Florida, where he’d spent most of his time incarcerated.

“What I don’t understand is why the Federal Bureau of Prisons would transfer a super high-publicity inmate, who is a known snitch, to general population of a high-security prison,” a former federal prison warden told the Associated Press.

While the events leading up to Bulger’s death remain murky, reactions to his death were immediate and clear. Family members of his victims were literally popping champagne corks at news of his demise. “He deserved a slow death and that’s what I hope he got,” Tommy Donahue, whose father was killed by Bulger, told CBS.

Whitey Bulger’s years of mayhem stretched from at least 1973 to 1985, a period when the Irish-American crime boss led the Winter Hill Gang in a neighborhood of Somerville, northwest of Boston.

His victims included a rival Boston tough, Paul McGonagle, who disappeared in 1974. McGonagle’s remains were found in 2000 in a shallow grave near a river. Decades later, after Whitey’s capture and during his trial, a witness testified that Bulger used to drive past the site and say: “Drink up, Paulie.”

Bulger wasn’t just a crime boss—he was also an FBI informant, who played a key part in the downfall of his federal handler. (Elements of Bulger’s story are woven throughout the 2006 Best Picture winner, “The Departed.”)

From the 1970s through the ’90s, Bulger cooperated with police and the Feds, feeding information about members of an Italian-American crime family in Providence in a deal that protected him from prosecution. He ultimately fled Boston in 1994 after his FBI handler, John Connolly, warned him about a pending federal indictment. Connolly was charged with obstruction of justice for warning Bulger and received a 10-year sentence.

Bulger’s criminal career contrasted starkly with that of his brother, William, who rose to become president of the Massachusetts Senate and was later selected to head the state’s public university system. William Bulger, in 2003, was forced out of his $356,000-a-year University of Massachusetts job by then-Massachusetts Governor Mitt Romney for failing to aid in an investigation of his fugitive sibling.

Whitey Bulger spent 16 years on the run alongside his longtime girlfriend, Catherine Greig. They were finally arrested in 2011 in Santa Monica, California where they had been living under the guise of mellow retirees.

Greig went to trial in 2012, a year before Whitey. She pleaded guilty to conspiracy charges related to harboring a fugitive and identity fraud, and was sentenced to eight years in federal prison. Unlike many of the mobster’s associates, Greig never turned on Whitey. Sources say that most recently, she was living with members of his family.

In November 2013, Bulger was sentenced to two life terms, plus five years, as the orchestrator of a criminal enterprise that U.S. District Court Judge Denise Casper called “Unfathomable.” He was 84 at the time and served much of the next five years at a prison in Sumterville, Florida, before his transfer to West Virginia.

In the wake of Bulger’s murder at Hazleton, attention focused on two inmates, both from Massachusetts and both with organized-crime connections: Fotios “Freddy” Geas, a hitman whose disdain for duplicitous men like Bulger was well-known, and Paul J. DeCologero.

Both were filmed entering Bulger’s cell shortly before guards discovered the 89-year-old dead. There was no camera directly inside the room.

Geas is serving life at Hazleton for his part in several murders, among them the 2003 shooting of Genovese crime boss Adolfo “Big Al” Bruno, who was slaughtered in a Springfield, Massachusetts parking lot.

Were Geas and DeCologero responsible for Whitey’s death? Will the government pursue charges against them, or others? Could Bulger’s murder go unpunished?

In the wake of pretrial detainee Jeffrey Epstein’s apparent suicide in Manhattan in August 2019, federal prison officials are under increased scrutiny to account for the safety of their charges, says Murphy, of the Boston Globe.

It is not unusual for cases involving the death of an inmate on the inside to drag on for years. Referring to past prison slayings in general, Murphy says the reason for a prolonged investigation could be something as plain as a lack of evidence; or, the government could be certain of the identity of the killer or killers and weighing a death penalty case.

Historically, Murphy added, there isn’t abundant sympathy inside or outside the criminal justice system for a man serving time for multiple violent murders.

“This is a guy who led a double life for years,” she says. “He left a trail of victims. On the flip side, his own associates turned on him when they found out he’d been secretly providing information to the FBI for years. Once all that was exposed … there were very few people who stood by him.”

[UPDATES: On August 18, 2022, three men were charged with murdering Bulger: Fotios Geas, Paul J. DeCologero and Sean McKinnon, all of whom were in prison with Bulger, were charged with conspiracy to commit first-degree murder. It’s unclear why it took four years for the men to be charged in the case, given they were quickly identified as suspects.

On September 6, 2024, Geas was sentenced to 25 years for Bulger’s murder. DeCologero was sentenced to four years in prison in August 2024 on an assault charge related to Bulger’s murder. McKinnon pleaded guilty in June 2024 to lying to FBI special agents and was given no additional prison time. ]

Related Features:

The Most Credible and Most Outlandish Theories About Jimmy Hoffa’s Death

Why Did the Working Class Love John Gotti So Much?

Lufthansa Heist Murders: How Paranoia and Greed Led to the Deaths of 6 Mobsters and Associates