In 2005, Tommy Ray, a special agent with the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, came up with an idea that would revolutionize cold-case homicide investigations: making a game out of it.

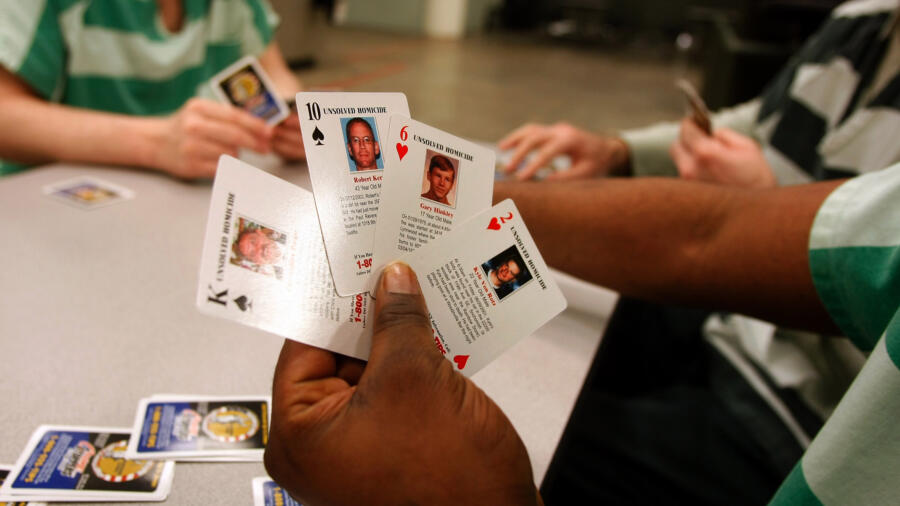

Details from unsolved cases were put onto the faces of traditional 52-card decks and distributed to inmates, in the hopes that—between hands of poker—the incarcerated would give investigators new leads. Although the idea was originally greeted with skepticism, the cards proved to be a rousing success, and are now being implemented in 18 states and counting.

A&E True Crime spoke with Ray about how the idea came about, why the cards have been so effective and whether victims’ families are on board with the unorthodox program.

How did the idea first come to you? Was there a lightbulb moment?

I’d had a case, several years ago—a drug case— where I went to interview a guy and he said to me, ‘You want my brother, you don’t want me.’ I’d contacted the wrong prisoner at this prison. So I said, ‘Well, since I dragged you out, have a Coke; it’s on me.’

We’re sitting there, having a Coca-Cola, and I said, ‘I also work cold-case homicide, so… you don’t know anything about any old murders, do ya?’

He says, ‘Well, I know about this one murder, and it’s already been solved.’ I asked, ‘What case is that?’ and he told me—Angela Nash. I knew that case wasn’t solved. He said, ‘Well I thought the boyfriend had been arrested, because he admitted to me that he killed this girl.’

So he gives me this information, and I’m able to go out and solve this 5-year-old homicide case. Just coincidentally. I’m thinking, if we had a way to contact all these inmates, there’s no telling what information we could get.

And putting the cards in there, it was just tapping another resource.

So we were having one of our cold-case meetings. They had the cards already for fugitives, people with outstanding warrants, but those people were being arrested before the cards were issued. I said, ‘Why don’t we put unsolved homicides on them? Missing persons?’ [One guy] said to me, ‘That’s the dumbest idea I’ve ever heard.’

[Stream episodes of Cold Cases Files in the A&E app.]

What goes on the card?

The picture is a victim. Anyone under 18 years old is in silhouette.

[Editor’s Note: The cards also feature details from the case and a tip line telephone number.]

Why the resistance within the department?

Cost. Just coming up with the money for the cards.

Initially we gave them away, and the first deck we were able to get a federal grant to help pay for some of them. I think we got 145,000 decks. It started in the county jail of Bartow, Florida: 4,000 or 5,000 inmates. For the first two or three months, everyone was like, ‘What happened to your great idea about the cards?’

I said, ‘Just be patient.’

After about the fifth or sixth month, a detective friend of mine called me up. He said, ‘I got a call. I’m going to be able to solve the Thomas Grammer case.’

We did it. Working with the crime stoppers and the attorney general’s office we were able to get enough cards for every state inmate in Florida. Within a couple of months… there’ve been two cases solved: James Foote… and Ingrid Lugo.

So, you know: bingo.

How did you pick the cases to put on the cards?

I looked at them and picked the ones that seemed the most solvable. Ones where you had witnesses, you have a vehicle leaving the scene. A lot was from [unsolved] murders [from] most of my career. I started working cold-case homicide in 1982 for the Polk County Sheriff’s Office. I tried to [include] every case that we had.

Surely law enforcement has tried other ways to get cold-case information to prisoners before. Why do you think the cards are so effective?

We’ve tried fliers, putting them up in jail. They even had a video feed, doing a cold-case review. But I just think it’s more personal when you’ve got that card in your hand, the photograph of the victim, and you’re sitting there staring at it. I think it has more of a psychological effect.

Plus it would start a discussion sometimes amongst the card players. Other than working out, that’s all they can do—sit and play cards all day.

Do these cards lead to prisoners going to authorities with information they knew but had never forked over? Or do they lead to confessions between prisoners over cards, which in turn lead to prisoners turning each other in?

It’s a combination of both. There was a case… he was in prison in Live Oak (Florida), and he goes to another inmate while they’re playing at cards and says, ‘See that guy and girl’—it was a man and a woman [on the card]—’My brother killed him and I killed this b—-.’ We started working that case up.

What about the victims’ families? Is there ever hesitation about giving inmates access to cards with their dead relative’s face on them?

There was, initially. This one girl—she was sexually abused and thrown over an overpass—and her mother didn’t want her daughter on cards, inmates having her daughter’s picture, looking at her, getting off on it. But once [the cards] started working she called and said, ‘Please put my daughter on the next deck of cards.’

When I first came up with the idea, I said to another homicide detective, ‘If we just solve one case, it’ll be worth it.’

Across the United States, they’ve solved at least 35 to 40 proven cases. Luckily, it’s snowballed.

Related Features:

Like What You’ve Read? Sign Up for Our Free A&E True Crime Newsletter

The Austin Yogurt Shop Murders Cold Case: Revisiting the Scene of the Crime More Than 25 Years Later

Is a Serial Killer Responsible for 8 Unsolved Murders in Virginia?