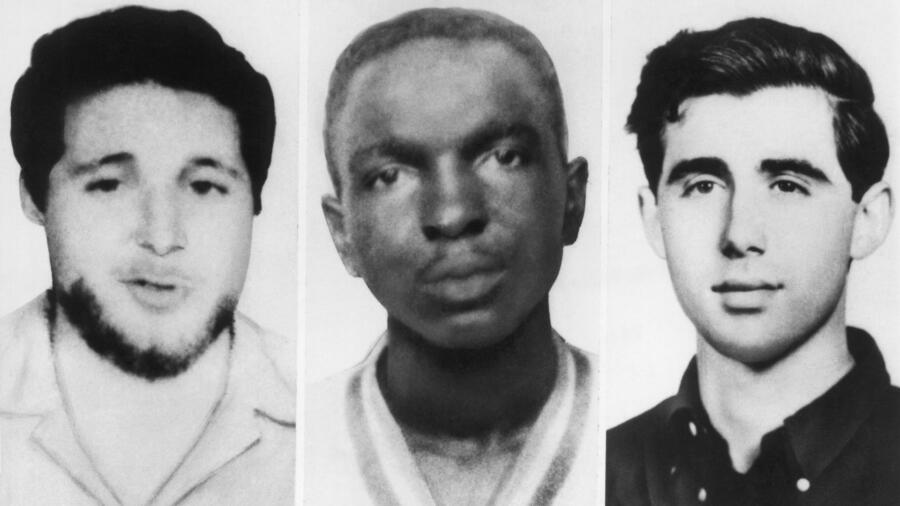

In the summer of 1964, more than 20 members of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan brutally murdered three civil rights workers — James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner — in Neshoba County, Mississippi.

The killings, which came to be known as the Mississippi Burning murders, went unsolved for 41 years. In his memoir, Race Against Time: A Reporter Reopens the Unsolved Murder Cases of the Civil Rights Era, journalist Jerry Mitchell chronicles how his investigations broke that case, along with three other infamous cold cases from the Civil Rights era: the 1963 killing of NAACP leader Medgar Evers, the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham that caused the deaths of four young girls and the 1966 firebombing murder of civil rights activist Vernon Dahmer.

Mitchell, a Pulitzer prize finalist and 2009 MacArthur Fellow who worked as an investigative reporter for The Clarion-Ledger in Jackson, Mississippi for more than three decades, spoke with A&E True Crime about how to handle cold cases, the FBI’s harassment of Martin Luther King Jr. and his role in the oldest prosecution of a serial killer in U.S. history.

You’ve been writing about cold cases for decades now. What inspired you to go that route with your reporting?

I saw the 1988 movie Mississippi Burning; that film sent me down that path. What really upset me was the fact that there were all these Klansmen involved in killing three young men, and not one of them had ever been prosecuted for murder. That just upset me to no end.

How did so many Klansman rally together and commit the crimes you covered?

The Klan believed the civil rights movement was an invasion. It was a whole rallying point for the group. The Klan leader told them that the Mississippi Summer Project (a volunteer campaign in 1964 that attempted to register African American voters) was an invasion. And so the troops were all fired up, so to speak.

You’ve received several death threats from the KKK. How did you deal with that?

With the death threats, in some cases, I called the FBI, and they were investigated. You want to be careful. You want to be smart, but you also don’t want to be intimidated. I had that mentality the whole time. I think of these guys as bullies. They were trying to intimidate me, to get me to stop doing stories. But I wasn’t going to stop.

Why did so many Klansmen talk to you, despite it not being in their best interest?

I think they saw me as one of them, to some extent: my upbringing is as a Southerner, my race—I’m very much a WASP—stuff like that. And so they said, ‘Come on in. Come talk to me.’ I even got asked to talk to Bobby Cherry (a Klan leader who was convicted of murder in 2002 for his role in the 1963 Birmingham bombing at the 16th Street Baptist Church).

Regarding the Birmingham church bombing, do you think the FBI made the right decision to refuse to share information with local officials at the time?

Maybe at that point in time, that was the right decision. But I don’t think the idea—of not sharing the information in general—was a good idea. I don’t know why they didn’t. There were people who wanted to [investigate] the case. In a couple of cases I worked on, they shared their case files with Mississippi authorities. That eventually happened in the case of Vernon Dahmer and then, later, in the Mississippi Burning case.

How did the FBI foster mistrust during the civil rights era?

No agency is perfect or completely trustworthy. There are lots of legitimate questions to ask about the FBI’s behavior during the civil rights era.

The once FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, for instance, believed that Communists were behind the civil rights movement. Then he did everything he could to discredit the movement. The FBI actually sent a letter to try to get Martin Luther King Jr. to commit suicide. They tried to intimidate him.

Stream hundreds of episodes of A&E’s classic crime series and specials, like Dog the Bounty Hunter, 60 Days In, and After the First 48, with no commercials.

How did they do that, specifically?

They sent him an audio sex tape. They had tapes of him having sex with women other than his wife, and sent that. They sent him a letter whereby they seemed to be hinting at suicide. Like, ‘You would be doing society a favor’ kind of thing.

Do you believe journalistic objectivity can be upheld, or should it be, when reporting on a group like the Klan?

Objectivity is a really interesting word. I think one of the problems is it means different things to different people. Maybe an easier way to think about it is being fair. Even when I dealt with these Klansmen, I gave them their say. I tried to, in spite of everything.

Is there a civil rights era cold case—or a glaring unaddressed injustice—that you think could still be solved but hasn’t been?

So many murder cases are not viable anymore. Suspects and witnesses are dead, or there’s just not enough evidence to bring cases to trial. Probably the one people would think of is Carolyn Bryant in the Emmett Till case. [Till was a 14-year-old Black boy lynched in 1956 for allegedly offending Bryant—a white woman. Her husband, who later confessed to the brutal killing, escaped conviction at the time—in part because she testified falsely at his trial about Till’s conduct.] The question would be, what do you charge her with? And what evidence do you have against her? I know the grand jury, in 2007, declined to indict her on manslaughter charges.

She later recanted her testimony to the author of the 2017 book The Blood of Emmett Till, saying her husband had forced her to fabricate the affront, and that Till had never touched or harassed her, right?

She did lie and we have proof of that. So, what can you do about that? [Some have suggested a perjury charge]. It’s a little more difficult than I think people realize. You’ve got to have witnesses. And if she’s the only witness, I don’t know. She’s obviously putting her best spin on it, ‘I knew nothing about it, I didn’t realize they were going to kill him.’ And that’s been her story. And if that’s the only way you get it in as to her statement, then obviously the jury hears all that, too.

Your reporting also played a crucial role in the oldest prosecution of a serial killer in U.S. history—that of Felix Vail. Could you talk about that case and did you pursue that matter the same way you did the civil rights era murders?

I did. The mother, Mary Rose, approached me. Her daughter, Annette, had married Vail, who was a serial killer. She had an inch-and-a-half thick folder of information. And so I was able to use that as a basis to start and then begin to investigate it. It eventually all came together.

Felix Vail was married to a woman by the name of Mary Horton Vail. They married in 1961, she supposedly drowned accidentally in 1962. It was ruled accidental, despite the fact that Felix had taken out two separate life insurance policies on her, including one she didn’t sign. Even though the deputies were suspicious about what happened, the district attorney failed to pursue the case. And so Vail was never arrested in that case.

And then he had relationships with a lot of women, [including one] with a woman named Sharon Hensley. She disappeared in 1973.

And the third one—and these are all the ones that we know of—was Annette Craver Vail in 1984. Anyway, Annette’s mother was the one who came to me and asked if I’d be interested in writing about a serial killer living in Mississippi, and of course I was.

You end the book by stating, ‘We must remember, to point our compass towards justice. We must remember, and then act.’ Could you unpack that statement? And how can we continue to do that in this so-called era of fake news?

I believe journalism is a noble profession, and we have to keep doing what we’re doing and remain professional. When people in power don’t like what we’re doing and they’ve tried to disparage or even kill the messenger, that’s as old as time. So we have to remain true to our standards and remain professional and true to the truth and just report the truth and go from there.

Related Features:

Investigative Journalist Billy Jensen on Using Facebook to Solve Murders

Why 2020 Will Be a Groundbreaking Year for Forensic Genealogy and Solving Cold Cases

What Are Some of the Oldest Cold Cases That Have Recently Been Cracked Open?

Why Aren’t Police Solving More Murders with Genealogy Websites