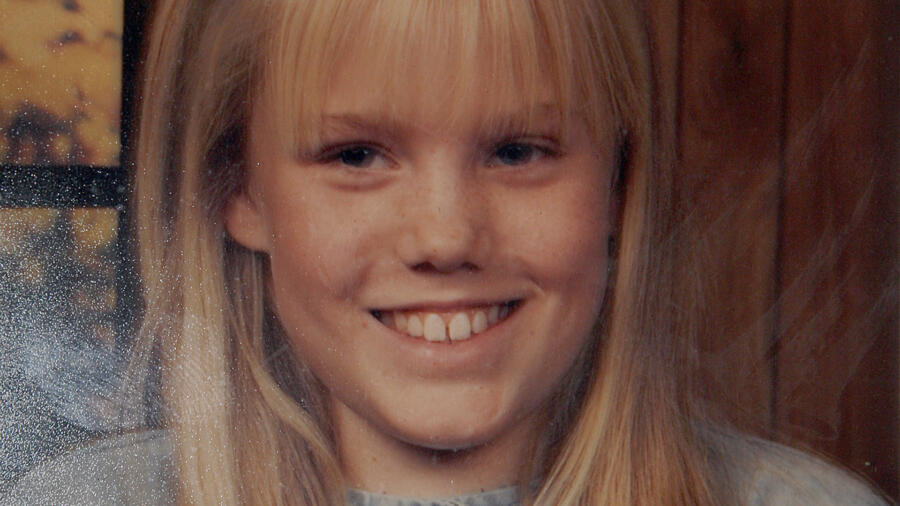

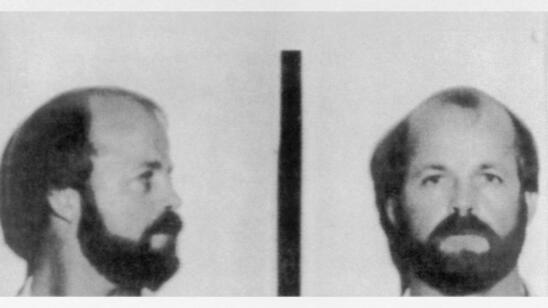

On June 10, 1991, 11-year-old Jaycee Dugard walked up the hill to her school bus stop in South Lake Tahoe, California for the last time. That day, Phillip Garrido and his wife, Nancy, pulled up beside Dugard in a car. Phillip was on parole after serving less than 12 years of his combined 55-year sentences for kidnapping and rape, and was looking for his next victim. The couple attacked Dugard with a stun gun, abducted her and drove her 170 miles away to Antioch, California. For the next 18 years, the couple imprisoned her in the backyard compound of Phillip’s mother’s house, torturing her with sexual and psychological abuse.

When she was finally freed on August 26, 2009, she was a 29-year-old woman with two daughters—ages 11 and 15—who had spent most of her life in captivity. (Her daughters’ names are not public.) During that time, she only left the backyard compound for certain supervised trips, and then only after the Garridos had spent years terrifying her into obeying them. She didn’t know how to drive and hadn’t seen a doctor since she was 11, not even during her two pregnancies. In fact, for 18 years, the Garridos hadn’t even allowed Dugard to speak or write her own name.

Dugard and her daughters finally gained their freedom thanks to alert police officers Lisa Campbell and Ally Jacobs at the University of California, Berkeley, who saw Phillip walking with Dugard’s two daughters one day and knew something wasn’t right. During Dugard’s 18 years of captivity, parole officers made 60 visits to Phillip’s house without discovering he’d kidnapped again—even after neighbors reported girls living in his backyard. Thanks to Campbell and Jacobs’ insistence, parole officers finally investigated and discovered the truth. In 2011, Phillip and Nancy received sentences of 431 years to life and 36 years to life, respectively.

Ten years after her rescue, Dugard’s life has changed dramatically. She immediately reunited with her mother, Terry Probyn, fulfilling one of the “dreams for the future” Dugard had written down in 2006 when she was still a captive trying to survive. She’s also checked off almost all of the other dreams on that list: She’s seen pyramids in Belize, ridden in a hot-air balloon, learned to drive, swum with dolphins, taken a train ride, learned to sail an old-fashioned sailing craft, gone horseback riding and written a best-selling book, A Stolen Life: A Memoir (2011). She’s also done some things she may never have imagined, like start a foundation and see Lady Gaga and Beyoncé in concert.

Starting this new life and reuniting with her family has been joyful but also difficult. Dugard and her daughters were traumatized by their captivity and required therapy and support to help them acclimate to their new lives. Using a clinical service called Transitioning Families, Dugard began to build a home for herself and her children away from the rapist who had fathered them and his complicit wife who forced the girls to refer to her as their mother. A lot of this therapy was built around interacting with horses, giving Dugard and her daughters the chance to learn how to ride.

Slowly, Dugard began to move through the life milestones that the Garridos had stolen from her and her children. She moved them into their own house, enrolled her daughters in school and adopted pets that Phillip couldn’t take away, as he often did to manipulate her during captivity. Dugard’s sister Shayna Probyn, who is ten years younger than Dugard, taught her big sister how to drive—a fact that tickled Dugard since Shayna was only a baby the last time she saw her. Dugard earned her driver’s license within a year of her release, and received a gift of a new car from a generous stranger.

Dugard has also gotten involved in helping other survivors and their families. In 2010, Dugard started the JAYC Foundation to serve families like hers who have experienced severe trauma (“JAYC” stands for “Just Ask Yourself to Care”). In 2015, she collaborated with the psychologists Rebecca Bailey of Transitioning Families and Abigail Judge of Massachusetts General Hospital on a presentation critiquing the use of the phrase “Stockholm syndrome.” This phrase refers to a specific incident in 1973 and, they argue, doesn’t actually reflect research about how captive people relate to their captors. In presentations at Yale University and Harvard Medical School and in New Orleans, Dugard and her colleagues argued the phrase is misleading and hurtful to survivors, and suggested a new phrase: “adaptation processes.”

In 2016, Dugard published a second book, Freedom: My Book of First, detailing her life as a free woman. In it, Dugard describes her everyday triumphs and struggles, like trying to live a private life when there is so much media interest in her. In public, she is still nervous that people will recognize her face or her name (though some mistake her for a member of the Duggars, the reality TV family with all the kids). Yet overall, she is very happy with her life, and happy that she and her daughters are finally free.

Related Features:

Kamiyah Mobley’s Abductor Raised Her as a Daughter for 18 Years

How ‘Live PD,’ AMBER Alerts and Social Media Have Helped Find Missing Children

Madeleine McCann’s Disappearance: Over 10 Years Later, What Went Wrong

Cleveland Kidnapping Survivor Michelle Knight: Healing After 11 Years in Hell