Warning: The following contains disturbing descriptions of violence. Reader discretion is advised.

In the early 1870s, someone began terrorizing children near Boston. Residents of Chelsea, East Boston, Dorchester and Jamaica found kids, ranging from ages 3 to 9, tied to telegraph poles or fence posts with injuries all over their bodies, according to The New York Times. The incidents seemed to escalate, and two children were later found dead.

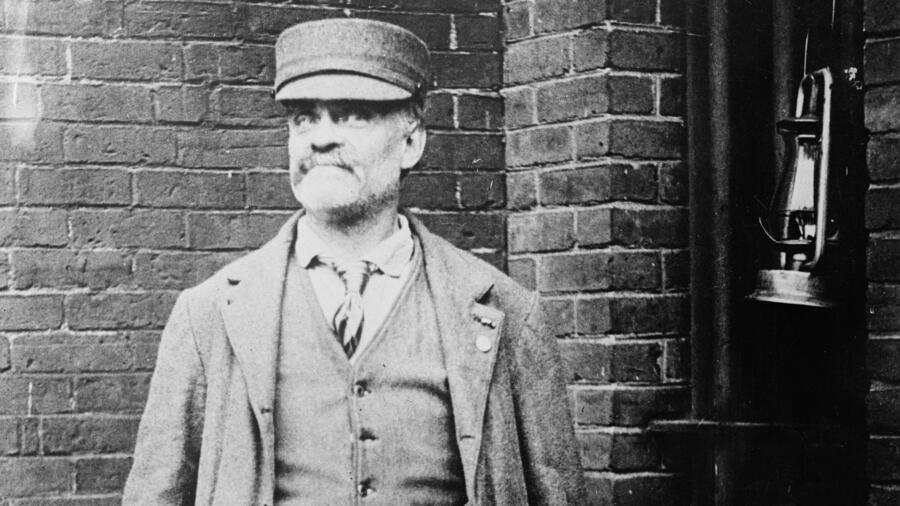

That “someone” was Jesse Pomeroy, a pre-teen who tortured and, ultimately, killed at least two children between 1871 and 1874. When asked why he committed such terrible crimes, Pomeroy maintained that he did not know, that something made him do it.

Pomeroy, later nicknamed the “Boston Boy Fiend,” was a huge topic of conversation in Boston and beyond, and many theorized possible explanations for his behavior. Some pointed to his childhood: Pomeroy was a loner who was often bullied because of a birth defect that covered one of his eyes in a thick white film. He also had an unstable home life. Others believed he committed the crimes because he spent most of his free time reading “dime novels” that depicted violence. Still others said he was simply born that way.

But how could Pomeroy have committed multiple murders without knowing why? What compelled him to act this way? Dawn Keetley, an author and English professor at Pennsylvania’s Lehigh University, explores these and other questions in her book Making a Monster: Jesse Pomeroy, the Boy Murderer of 1870s Boston. Keetley spoke with A&E True Crime about Pomeroy’s life and crimes—and shared her new 21st century theory for why Pomeroy did what he did.

What was Pomeroy accused of exactly? What crimes did he commit?

Between 1871 and 1872, when he was only 12, Pomeroy remorselessly tortured at least seven young boys. He was sent to a juvenile reform school, where he was a model inmate and was released early after serving only 17 months.

But just over a month after his release, 10-year-old Katie Curran vanished after setting off to buy school supplies from the Pomeroys’ store in Boston. One month after that, in April 1874, the brutalized body of 4-year-old Horace Millen was found on the Dorchester Bay marsh. The same day, Pomeroy was arrested for Millen’s murder. At the time, he was only 14.

[Stream Invisible Monsters: Serial Killers in America in the A&E App.]

After an extensive search of the Pomeroys’ store, Katie Curran’s body was discovered in the cellar, also brutally stabbed.

How did Pomeroy explain himself?

He went back and forth between denying he murdered anyone and indirectly admitting that he did by repeating, ‘I couldn’t help it,’ and, ‘Something made me do it.’ Later in his life, he insisted, ‘I remember nothing from that time.’ He never offered any details of his crimes, even when he seemed to admit he had committed them. And he never admitted responsibility.

What was the public reaction to his case?

Pomeroy’s trial for the murder of little Horace Millen began in December 1874, and it riveted not only Boston, but the nation. Pomeroy was America’s first known serial torturer and, if he hadn’t been caught, he would no doubt have become America’s first serial killer.

[Editor’s note: Pomeroy also confessed to Curran’s murder. The FBI’s current definition of a serial killer is someone who unlawfully kills two or more victims in separate events. Pomeroy is, in fact, considered a serial killer by today’s definition and he is the youngest serial killer in U.S. history.]

What was his trial like? What arguments did lawyers make?

Pomeroy’s lawyers used an insanity defense. They argued that he suffered from what was called in the 19th century ‘moral insanity,’ that he was afflicted by an ‘irresistible impulse’ to torture and kill. They used Pomeroy’s own words about some force driving him, against his will, to torture and kill as a sign that Pomeroy suffered from mental disease. This narrative didn’t supply a motive; it replaced motive with the concept of disease.

The attorney general based his case on the legal presumption that all persons were sane until proven otherwise. He also encouraged the jury to conflate sanity with premeditation, which could occur in the very second before the crime. Because Pomeroy was clearly sane, according to the prosecution, when he lured 4-year-old Horace Millen to an isolated spot and brutalized and killed him, he therefore acted intentionally and was therefore culpable.

As the attorney general said in his closing, Pomeroy consistently displayed ‘unusual talent and shrewdness,’ and his acts ‘were not to be classed under the head of insane conduct, but of depravity.’

Jury members were swayed by the prosecution’s narrative and found Pomeroy guilty. The judge declared his death sentence.

What consequences did he ultimately face?

At the time of his trial, he was the youngest person in Massachusetts to face the death penalty, and not only was his trial front page news, but so was the long-running debate over whether he would actually be executed. In the end, the governor of Massachusetts commuted Pomeroy’s sentence and Pomeroy spent more time in solitary confinement than anyone else ever has. He went into [Charlestown State Prison] when he was 14 in 1874 and he died in prison in 1932. For almost all of that time, he was alone.

What were the prevailing theories about why he committed these crimes?

There were three major theories that Pomeroy’s contemporaries used to explain his crimes. One, that he suffered from ‘moral insanity,’ or an ‘irresistible impulse’ to torture and kill that anticipated 20th-century diagnoses of psychopathy.

Two, that he was shaped before birth with an instinct for blood, stamped in utero with a ‘maternal impression,’ because his pregnant mother visited the slaughterhouse where her husband worked.

And three, that he imitated and was even ‘possessed’ by the ‘savage cruelty’ of Native Americans and white renegades [depicted] in the pages of frontier dime novels. He consumed these books voraciously and read around 60 of them, starting at age 9. And, indeed, my research into Pomeroy’s reading habits did find a startling likeness between what he may have been reading and what he did to his victims.

What were some of the ripple effects of Pomeroy’s crimes?

The Pomeroy case got swept up in the late 19th-century moral panic about the dire effects of dime novels, which became an important historical context for his crimes. Hundreds of Americans believed that Pomeroy’s dangerous reading habits provided, as one editorial put it, ‘sufficient explanation of his murderous inclinations.’

The middle-class arbiters of taste were becoming increasingly worried about the rise in cheap reading material for the working-classes—sensational newspapers and dime novels. They worried specifically about the dangerous slide in morality they believed would follow from this reading, and Pomeroy’s violence, which seemed right out of a Western dime novel, proved their point.

Some people have theorized that he committed the crimes because his father abused him. What do you make of that?

From the moment he came to the media’s attention, Pomeroy was the constant subject of rumors, distortions and utterly fabricated stories, all of which persisted despite a lack of evidence. Pomeroy’s own inability to explain himself only fanned the flames of these baseless stories when he was alive. But people have routinely imposed on him what they want to believe.

The story of an alcoholic and abusive father has been the reigning story [to explain why some people torture and kill] since the middle of the 20th century. Serial torturers and murderers must, we think, have been abused as children. It’s a powerful story and it’s often true. But it’s not the only story and, in the case of Pomeroy, it’s not a true one. There is simply no evidence for it whatsoever.

Pomeroy’s case demonstrates that we must put aside preconceptions and familiar paradigms of human behavior and human crime and look steadfastly at what facts we can find.

What’s your theory on why Pomeroy behaved the way he did?

When he was only a few weeks old, Pomeroy’s mother took him to get a smallpox vaccination because there were waves of smallpox epidemics in Boston throughout the mid-19th century. Pomeroy’s mother claimed this vaccination catastrophically damaged her infant son and left his body covered with weeping sores for months. She was unable to touch him and she later said, ‘I think his vaccination had more effect on him than anything else.’

It is quite likely that Pomeroy’s dire reaction to his smallpox vaccination caused him moderate to severe pain and chronic stress at an age when he was too young to grasp consciously why he was suffering. The reaction also interfered with the crucial process of attachment with his mother.

Both chronic stress and failure of attachment in early infancy have been directly and repeatedly linked to changes in the brain that can cause impulsive, violent and even psychopathic behavior. Pomeroy’s utter lack of affect and his complete lack of remorse may have developed in those early months when he was in severe pain, when his attachment to his mother was broken.

Related Features:

Is There a Minimum Age for Being a Murderer?

The Offenders Behind 3 Court Cases That Changed Lifetime Imprisonment Laws for Juveniles

Was a Bad Childhood to Blame for ‘Night Stalker’ Richard Ramirez Becoming a Serial Killer?