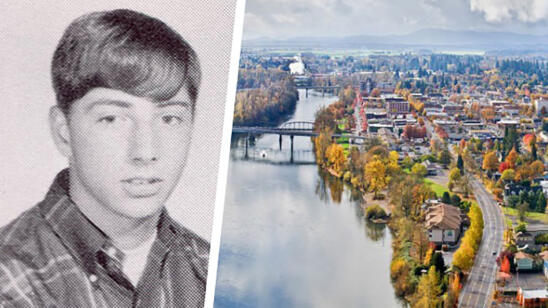

Firefighter and arson investigator John Orr of California’s Glendale Fire Department had a way of showing up very quickly at the site of a fire and going right to the point of origin. He was a respected authority and often in the press.

From the mid-1980s to 1991, a wave of arsons swept through Central and Southern California. They caused tens of millions of dollars in damage, and many of the fires were investigated by Orr. But there was an even greater cost—when flames raced through a Pasadena hardware store in 1984, four people (one shopper, her toddler grandson and two employees) died. Orr ended up being undone by a tell-tale fingerprint left behind at one fire, as well as his unpublished novel, Point of Origin (the fictional arsons were eerily similar to the ones plaguing the state). Orr was sentenced to four consecutive life sentences.

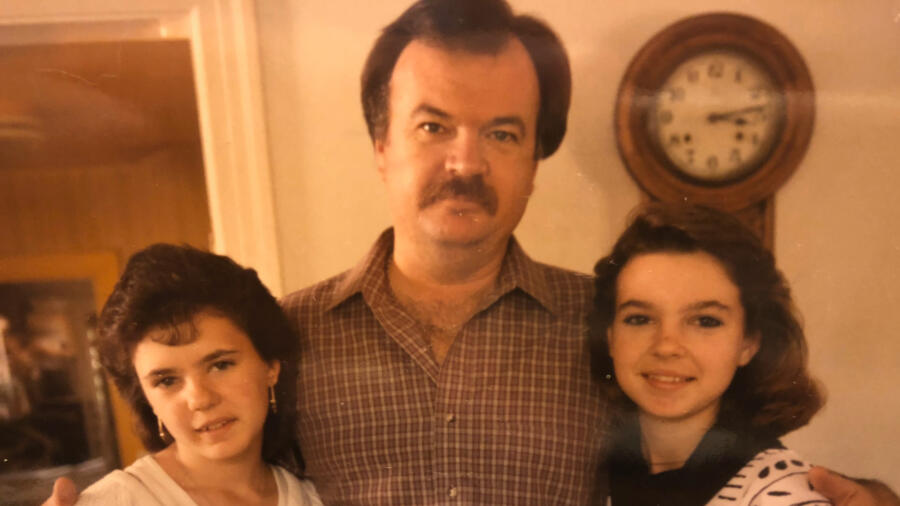

In Burned: Pyromania, Murder, and a Daughter’s Nightmare, journalist Frank Girardot, Jr. examines the incendiary true-crime story. His co-author Lori Orr Kovach, who was 17 when her dad was arrested, spoke with A&E True Crime about when she started doubting her father’s innocence, testifying at his trial to help him avoid the death penalty and how his actions affected the rest of her life.

Were you proud of your dad when you were a kid?

My sister [Carrie] and I looked at him as our hero. We would go to school and tell all our friends he was on the news. We would go to his work and he seemed important and highly respected. Everyone liked him. We were proud of him and we loved being with him.

What did you think when he was arrested for arson?

He told me, ‘This is a mistake. There is a firefighter lighting these fires, but it is not me. I know who it is and it will all get worked out.’

How did your life change when he was arrested?

I had just graduated high school. My plans of going to college [at the time] ended because I couldn’t get financial aid and my mom wasn’t getting child support anymore [because I was too old.] (But I did end up going to community college and getting into human resources, which was my dream.)

Before he was caught, he would still help us with things financially. That was gone. And his visits were gone. I got into an abusive relationship and he didn’t save me from that. Those are the things that I missed a dad for—I was being stupid and I had no dad to step in and help out.

Looking back, were there clues?

My dad said he had the matches, paper and cigarettes in his briefcase [his chosen fire-starter] when they raided his house because he would do training classes and show students the devices people used. He had excuses for things, and my sister and I were young enough that we didn’t know any better. We just took it at face value. We loved our dad and he was a hero; why wouldn’t we [believe him]? We’d never caught him lying to us before.

You write about testifying at your dad’s trial in 1998 (at age 23) to help him avoid the death penalty. What was that like?

I was in 100 percent save-my-dad’s-life mode.

When I was walking through the very full courtroom and didn’t recognize anyone, I looked at him. He was the only person I knew in there and he just stared at me. I thought he would at least mouth ‘I love you’ or something. But there was nothing. That’s one of the little things that bugged me at the time, but not enough to question his innocence.

Was he grateful for your testimony?

No, not at all. He never said a word about it. He didn’t even ask us. His attorneys asked.

When did you really start doubting him?

When he was arrested, I kept saying if I was being charged with something I didn’t do, I’d say, ‘You’ve got to believe me! I didn’t do this!’ He never did any of that.

All these little things kept popping up that were bothering me. Over time, I read my dad’s novel and the Joseph Wambaugh book (Fire Lover: A True Story). I talked to a family member who told me about catching him with cigarettes and confronting him because he didn’t smoke. My dad told that person that he was lighting brush fires, but not to worry because no one was getting hurt. That, to me, was the smoking gun. I was like, ‘Why didn’t you tell me that sooner? I went through all this to figure it out myself and you just could have told me that.’ “

Was it difficult to learn about your dad’s sadomasochistic sex life [in Burned] and how the arsonist in his novel would become sexually aroused by setting blazes?

It was disgusting to read his book, that was supposed to be fiction, and having in the back of my mind that he wrote it about himself. It was horrible to think that’s exactly what he was doing–watching something burn and doing these horrible sexual things.

How have your father’s actions affected the rest of your life?

I started to feel extremely guilty for testifying so he wouldn’t get the death penalty. I felt like that was wrong. If that was my child in that fire, would I have wanted the death penalty? Maybe. I think writing this book is about letting the world and the victims’ families know, ‘I’m sorry, I didn’t know what I was doing. He probably did deserve the death penalty. And I shouldn’t have [testified].’

If you could go back in time, what would you have done differently?

I would have attended the whole trial, not just the two days that my dad said I could come. I should have been privy to all the evidence if I was going to ultimately be asked to testify in the penalty phase. I also would have asked more direct questions and had long conversations with my dad about things.

As a parent, what shocks you the most about your father?

When I had kids, I got really angry at him for letting me testify. I would never have let my child go through that trauma and have that responsibility to save my life.

But what’s worse is someone I loved so much is capable of doing something so horrific. Sometimes, I think, just for a moment, if my dad loved me more, he wouldn’t have done these things and risked being taken away from his kids.

Is it hard knowing your dad put other people’s kids at risk?

That’s why I’m trying to [turn my story] into something positive by writing a book. It wasn’t me who did it. I didn’t know about it. And I’m trying to have the best life I can have, even given these crappy cards. If I could share that with other families who are going through things like this—for example, there was just another school shooting and the parents of that child are going to be devastated—[they can know] they’re not alone.

Check out the Cold Case Files episode, “Diary of a Serial Arsonist” for more on John Orr’s crimes.