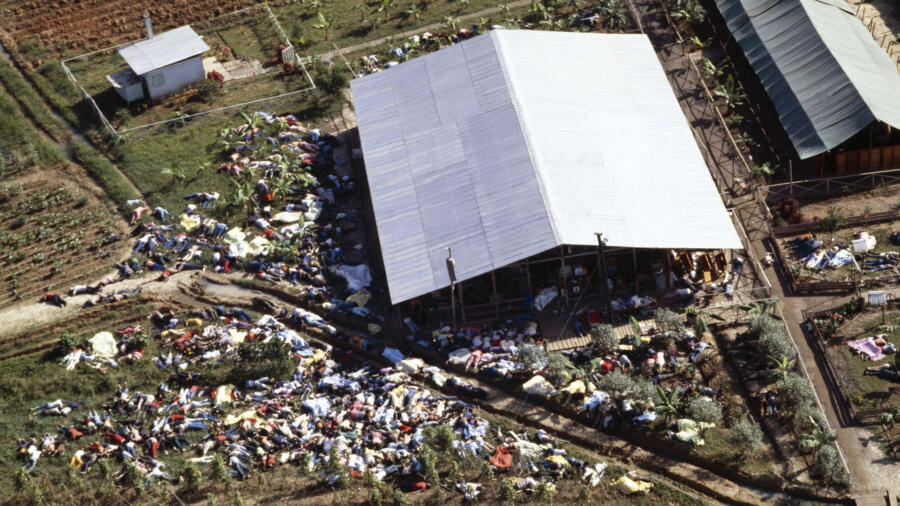

Many of us have heard the expression “drinking the Kool-Aid” when talking about people or groups blindly going along with bad or dangerous ideas because of pressure from others. But the term originates from a historical event much more tragic than the light-hearted phrase implies: the Jonestown massacre. On November 18, 1978, more than 900 men, women and children lost their lives on an agricultural settlement on the northern coast of Guyana in South America. The incident remains one of the largest single-day losses of American life, second only to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

The settlement itself was known as Jonestown, named after the charismatic pastor Jim Jones, who in 1955 founded a religious movement that would later become known as the Peoples Temple of the Disciples of Christ. Jones, an American pastor who preached peace and racial integration during the ’60s and ’70s, abruptly moved his flock to the Jonestown compound in 1977, promising them a utopian community and becoming increasingly isolated from life outside the settlement.

On November 18, 1978, fearing a siege from the U.S. government, Jones and his followers cyanide-laced Flavor Aid—not Kool-Aid as so many people think—and died en masse. The final death toll was 918. While there’s no question that Jonestown was a tragic event, many scholars are torn on whether to refer to it as a mass suicide or a mass murder.

For the almost 300 children who lived at Jonestown, there is no question that they were murdered by their parents or caretakers. When Jones told his followers to drink poison on November 18, parents and other members of the compound forcibly fed the concoction to the children with syringes and spoons. But the adults’ deaths are harder to understand: Did members of the Peoples Temple willingly choose to die—or were they coerced, or brainwashed, into drinking the poison?

“Everyone died for a different reason,” says Dr. Phyllis Deal, a sociology and psychology professor at Texarkana College. “Some of the adults believed in Jim Jones’s cause and followed him to the end. Others were miserable living in the compound and just wanted everything to be over.” Some followers, sensing danger, left the compound in the hours before the event and managed to escape. Still others were thought to have wanted to leave but felt unable to.

“Jones pitted people against each other, and his punishments [for defecting] were horrific,” Deal says. “People felt really disconnected and isolated, and Jones had people convinced that if they tried to leave, they wouldn’t succeed.”

Jones also had armed guards stationed at the edges of the compound, in order to keep “outsiders” away and prevent his followers from leaving. For this reason, Deal says, not every adult who took the poison at Jonestown did so willingly.

But it’s inaccurate to say that all the adults at Jonestown were murdered, says Dr. John R. Hall, research professor of sociology at the University of California at Davis and Santa Cruz, and author of a book about Jonestown, Gone From the Promised Land.

“To say everyone was murdered denies the agency and the solidarity of these people,” Hall says.

When Jones moved his followers to Guyana to live at the compound, Hall says, he originally referred to Jonestown as an “agricultural experiment.” Jones had been preaching elements of Marxism and communism since the 1950s, and his stated mission was to build a utopia where people of all races could live and work communally. But Jones, paranoid from years of drug abuse, was also convinced that the U.S. government saw their movement as a threat and wanted to tear the commune apart.

Daily, Jones fed his followers propaganda over loudspeakers about impending government raids and ran extensive “suicide drills” in preparation for a siege.

Tensions came to a head in November 1978, when California congressman, Rep. Leo Ryan, paid a visit to the compound to investigate the rumors of human-rights abuses. To Jones, Ryan’s visit meant that enemy forces were closing in.

(On the same day as the massacre, Ryan and four others were murdered on an airstrip in Guyana, as they were leaving Jonestown. Ryan’s group had included some defectors from Peoples Temple who asked to go back to the U.S. The murderer, Larry Layton, posed as one of the defectors, but was loyal to Jones and opened fired on Ryan’s group. Although sentenced to life in prison, he was paroled in 2002 after serving 18 years.)

“Certainly the children did not make an informed decision,” says Hall. “But the adults at Jonestown lived within their own bubble of reality, and in the end they had come to believe that their world was under siege from the outside.”

To understand this mentality, Hall points to two examples from modern history where large groups of people collectively took their lives. In 17th-century Russia, a religious sect called the Old Believers resorted to suicide out of fear of persecution. Likewise, in 73/74 CE, a group of Jews committed suicide at Masada in Israel rather than submit to the encroaching Roman army.

Like the people at Jonestown, Hall says, some societies choose death rather than live in a way that isn’t true to their beliefs.

“If you listen to the [recordings of the suicide], you can hear there are people who understood that they had a choice to die collectively rather than be subjected to an external force they regarded as illegitimate,” says Hall. “There’s a lot to be said about Jones being this diabolical figure, but the truth is that a lot of people willingly participated in this event. They prepared the poison, they distributed it to other people—it wasn’t just Jones acting by himself.”

(Listen to audio of the Jonestown deaths here. Warning: It contains graphic content.)

Still, to Deal, writing off the adults’ actions as strictly suicide is dehumanizing. “People joke about people at Jonestown ‘drinking the Kool-Aid,’ and that implies that they were stupid and gullible,” says Deal. “But in truth, they weren’t crazy or stupid. They were people who believed in a good cause and they were manipulated. For people to say ‘oh, they drank the Kool-Aid, they were just stupid cult followers’—it makes it easier to just dismiss the whole thing. It’s just so we can feel better. But we’re doing people a grave disservice by trying to imply that all the killings happened for the same reason.”

In the end, experts who study Jonestown agree that the deaths were neither wholly suicide nor wholly an act of murder—but paradoxically, a bit of both.

“It would be wonderful if we knew everyone’s mindset at the time so we could make a clear determination,” says Hall. “But we don’t. All we have are these shards of evidence that point to the complexity of the situation—and that’s really the only way we’re going to understand it.”

Related Features:

What Was It Like to Die From Cyanide Poisoning at Jonestown?

Watch Special: Jonestown: The Women Behind the Massacre

Rachel Jeffs on Escaping the FLDS Cult and Her Father Warren Jeffs

David Koresh and the Branch Davidians: 6 Things You Should Know