Warning: The following contains disturbing descriptions of violence, including sexual violence. Reader discretion is advised.

In June 1967, Henry Evers’ torso and other body parts were found floating on Biscayne Bay in South Florida. His wife, Betty, and their daughter, Jennifer, blamed the murder on David Katz, a drama student at the University of Miami who was allegedly having an affair with Betty. Katz was never indicted, and the “torso murder” went unsolved for 18 years—until Betty walked into a Los Angeles police station in June 1985 and confessed to killing her husband.

She told homicide detectives the murder had been “hanging over her head,” but that she had acted in self-defense when she shot Evers eight times. She later dismembered his body and disposed of it in the bay. A jury acquitted Betty at a second trial in April 1986, citing a lack of evidence to prove premeditation. Although she appeared guilt-ridden and remorseful for her husband’s death, Betty Evers didn’t blink when initially blaming Katz.

Sean Michael Laurent, an assistant professor at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and head of the Morality and Social Cognition Lab, who has extensively researched moral judgment and blame-shifting, says shifting blame is common and often a knee-jerk reaction that comes from fear.

“People learn at an early age that when you do something wrong and people find out, there are consequences, and they fear the repercussions,” Laurent tells A&E True Crime. “Some people are honest and accept responsibility, while others try to shift blame, almost like a natural reflex.”

A person doesn’t have to be narcissistic or a sociopath to engage in the blame game, even when pointing the finger at someone for a horrendous crime. In many instances, Laurent says, it’s a calculated risk—the other person will or won’t take the fall.

“If you’re going to shift the blame onto someone else, it certainly suggests a lack of compassion and empathy, and also, maybe not psychopathy, but a certain amount of willingness to let other people get harmed for your mistakes,” says Laurent.

The more serious the consequence, as is the case with murder where capital punishment and life imprisonment are possible outcomes, the more likely someone is to shift blame.

A&E True Crime looks at more killers who’ve blamed others for their horrendous crimes.

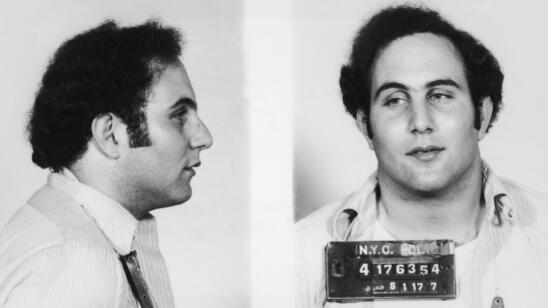

David Berkowitz (‘Son of Sam’)

Some serial killers deny their crimes, while others give morbid and terrifying confessions. David Berkowitz, the serial killer known as “Son of Sam,” did both.

In a police interrogation, Berkowitz, who murdered six people in New York City from 1976 to 1977 with a .44-caliber revolver, confessed to the shootings. Later, he backtracked, claiming he was just the lookout guy. Berkowitz blamed his neighbor John “Wheaties” Carr and Carr’s brother, Michael, as the shooters.

“There are some people who are pretty narcissistic, or pretty sociopathic, who don’t care if they are messing with other people,” says Laurent. “For them, shifting blame would be almost like a sport.” (Psychologists believe Berkowitz enjoyed terrorizing New York City.)

But Berkowitz’s blame-shifting, and conflicting accounts, didn’t end there. At one point, Berkowitz told detectives that John Carr’s black Labrador Retriever was possessed by an ancient demon and had ordered him to kill. Accomplice or cold-blooded murderer, Berkowitz pleaded guilty to the shootings and, on June 12, 1978, three judges sentenced him to six consecutive 25-years-to-life prison terms.

Brad Reay

In 2006, Brad Reay discovered that his wife, Tamara “Tami” Reay, a 41-year-old wife and mother who lived and worked in Pierre, South Dakota, was having an affair. She was reported missing by her lover and co-worker, Brian Clark, on February 8, 2006. Clark told dispatchers he believed foul play was involved and that Reay’s husband could be responsible for her disappearance.

Upon searching the Reay residence, investigators found blood on the garage floor and dripping from Tami Reay’s SUV. They also smelled a cleaning solution and saw blood smeared inside the vehicle. They arrested Brad Reay on suspicion of murder.

On February 10, 2006, authorities discovered Tami’s body in a wooded area north of Pierre. She had been stabbed more than three dozen times.

Brad attempted to blame his 12-year-old daughter, Haylee, stating he had witnessed the girl holding a bloody knife and hovering over her mother in a trancelike state. He claimed he tried to cover up the crime to protect his child.

“In some cases, a parent or someone else will shift blame to a child, because they don’t believe there will be any consequences for the child, that they are too young to understand their own actions,” says Laurent.

In January 2007, a jury rejected the claim of Haylee’s involvement and found Brad guilty of first-degree murder. He was sentenced to life in prison without parole.

Chris Watts

Like Christian Longo and Scott Peterson, Chris Watts sought to eliminate the obstacles standing between him and a new life. In each case, the obstacles were the men’s wives and children.

Watts had been having an affair with a co-worker and wanted a divorce. At their home in Frederick, Colorado, during the early morning hours of August 13, 2018, Watts told his pregnant wife, Shanann, about his infidelity. Upset, she threatened to take away their children. Watts became enraged and strangled Shanann. But he didn’t stop there. He then smothered his two daughters, Bella, 4, and Celeste, 3, to death with a blanket before dumping the bodies at his job site—his daughters in oil tanks and Shanann in a shallow grave.

At first, Watts told police he killed his wife after he confessed to the affair and she, in turn, strangled their daughters in desperation.

“Blame shifting is an extreme version of trying to justify your behavior, where you are so concerned with protecting your reputation, your job, your livelihood and other people’s impressions of you that rather than trying to justify what you did, you try to explain why it wasn’t you at all and why it was someone else or something else that led to it,” Laurent explains.

It wasn’t until letters he had written to his mistress surfaced, in which he confessed to planning the murders, that Watts finally admitted to killing his wife and daughters. To avoid the death penalty, he pleaded guilty to multiple counts of first-degree murder and was sentenced to five life sentences plus additional time for tampering with a deceased body.

Juan Carlos Chavez

Before he was executed by lethal injection on February 12, 2014, Juan Carlos Chavez didn’t show a bit of remorse for his unspeakable crimes.

Chavez, a handyman from Miami-Dade County, Florida, abducted 9-year-old Jimmy Ryce on September 11, 1995, as the young boy was walking home from school. Chavez brought the boy back to his trailer, where he sexually assaulted him.

When Ryce, who loved baseball and playing with his friends, heard a helicopter flying overhead, he attempted to flee out the front door. Chavez shot the child in the back and held him until he took his last breath.

Although a nationwide search ensued, two months passed before the owners of the trailer discovered Ryce’s backpack and a handgun inside. The child’s remains were found nearby.

After being charged with murder and sexual assault, Chavez shifted the blame to the son of Chavez’s former boss.

“I’m sure there are some people who are narcissistic or sociopathic, who wouldn’t care if they were messing with other people,” says Laurent.

While Chavez might have fit this description, the overwhelming forensic evidence, along with his confession, convinced a jury of his guilt. He was convicted of first-degree murder, sexual assault and kidnapping and sentenced to death on November 23, 1998.

Related Features:

Chris Watts Murder Case: The Most Disturbing Revelations from the Prosecution’s Discovery Files

David Berkowitz Confessed to Being the ‘Son of Sam.’ But Did He Really Act Alone?