“The FBI is not going to solve every crime,” says Dr. Kirk Yeager, the agency’s chief explosives scientist. “We need an informed public.”

Before his latest role, Yeager, spent 10 years as a physical scientist and forensic examiner for the FBI Laboratory’s Explosives Unit. He has not only deconstructed what bombs are comprised of, but the psyche of a bomber and the conditions that allow them to thrive.

From the 2002 Bali bombings to the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, understanding how these crimes unfolded is essential in preventing similar atrocities–domestically and abroad.

Yeager’s book, The Bomb Doctor: A Scientist’s Story of Bombers, Beakers, and Bloodhounds, unpacks myths about explosives and the people who devise them. He spoke with A&E True Crime about the science behind bombs and the motivations of their creators.

Why do suspects use bombs as a method to kill versus other methods that may seem easier?

You have what I call criminal motivation, which almost goes back to the seven deadly sins– all the darker parts of humanity and crimes of passion and anger. …Bombs are a tool that’s going to hurt someone just like a bullet. You [can] be present to commit the crime with a bomb. [Or, regarding a time bomb,] you can send or place the bomb so you’re not there when the event goes off. It gives the advantage of distance.

The other side of motivation is terrorism, which is people or groups of people lashing out against a power greater than themselves that they feel is oppressing them.

Bombs are very powerful; they unleash a lot of energy. [If] someone is trying to fight an adversary that has greater wherewithal and more power, bombs give them a tool that amplifies their power and their ability to induce damage. It also gives them a tool that allows them to do it remotely. When the event happens, the adversary can’t retaliate immediately, and it requires an investigation to figure out who did it.

How are bomb investigations unlike other types of forensic investigations?

After a bomb has gone off, the state of the evidence is a little different and difficult to interpret. Bombs release energy very violently, destroying things in contact with them. An analogy I use: You have a jigsaw puzzle. You open the box, throw out half the pieces, [then] light the other half on fire and beat them out with a crowbar. Try to figure out what the picture was by putting them back together. That’s kind of how a bombing investigation works.

You’re never sure you’ll have all the pieces of the device and be able to figure out how they all fit together to give you a working explosive. It’s a matter of chaos.

The most difficult part of my job and investigation is after a bomb goes off. It’s a little simpler if we interdict a plot before the bomb has detonated because everything is in one piece. That’s ostensibly the main difference there is in a post-blast situation.

What are some limitations to investigating an explosion overseas?

The FBI investigates bombings in the U.S. and abroad. As in any investigation, the complications are mainly figuring out what you have on the scene and who is responsible. Limitations come down to what can be collected after the bomb has gone off, and how difficult it is to interpret the chaos from the destruction the bomb has caused.

Limitations are more complicated [overseas] because it takes time to get to the event. The scene may not have been as protected or pristine as it would be in the U.S. That complicates the collection of evidence.

What are some common misconceptions about your line of work?

Historically, a common misconception on the other side of the aisle, from [the perspective of] bomb makers, is that everything is destroyed when a bomb goes off and there’s nothing left behind.

Looking back to the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s, many bomb attacks against airlines were not terrorism-related– they were suicide or murder attempts. The bomb makers in those cases believed that when the plane fell out of the sky, and there was a bomb on it, no one would figure out what happened due to the nature of an airline crash. [They also believed they] would collect insurance money because it would be ruled an accident.

In [most] historical cases…investigators figured out within a short period that a bomb was involved. They were able to trace it back to the person who placed the bomb on the plane.

Why is the Boston Marathon Bombing case unique or noteworthy?

It’s a horrific scene in any bombing where there are huge numbers of victims and the bomb goes off in a crowd. We’ve been very fortunate in the U.S. that we haven’t had a lot of those.

[The Boston Marathon bombing involved] two devices against the civilian population at a celebratory event. The two bombs are close enough that evidence from each of the bombs overlaps. When a bomb goes off, the explosive scatters things. They were close enough that there was some cross-scattering of evidence.

Then, you had people fleeing the scene and all these backpacks and things left behind. As investigators, one of the things we are concerned with is the secondary device. There was always the chance that one of those backpacks contained another device. That slows down response.

You [also] have victim recovery. We were lucky in this particular case that there was a medical tent near the finish line, meaning we had medical support on the scene. As horrific as it was, that at least limited some of the carnage that could have occurred.

As technology advances, so does access to bomb-making materials. How does that pose new obstacles for your line of work?

Technology always has two sides: It’s an enabler and it has a destructive potential.

When Alfred Nobel created dynamite, he gave society the ability to [facilitate] the Industrial Revolution. We were moving mountains, creating roads and mining ore at an unprecedented rate that allowed us to make steel to build skyscrapers and create our civilization. At the same time, he gave anarchists the tools to lash out against the government and society. And technology does that up the line to the current technology. Of the unmanned aerial system, the drone, to ChatGPT which coalesces and disseminates knowledge readily.

In terms of technology, the big change is how easy it is to access knowledge. The internet is a game changer across the board. [It teaches the public] anything from how to fix your car, to how to bake or cook whatever you’re interested in and to how to make bombs.

Technology has promulgated knowledge to a greater mass of people. Sometimes that knowledge is productive, sometimes that knowledge is destructive. That’s what we see every time there’s a technology out there. It evolves and hits the consumer public. It revolutionizes our lives in many ways, but it can also be misused– from the UAS [unmanned aircraft systems], to additive manufacturing, where people now can print casings for hand grenades instead of going to a military supply store and buying an old hand grenade to convert.

Do you work with other agencies to help stop bomb attacks?

The FBI, in partnership with [Department of Homeland Security] programs, educates vendors who sell [bomb-making] chemicals about suspicious purchases. Everyone is working together. No one wants bombs to go off and people to get hurt other than the bad guys who are using them. And we ought to work together to keep them from happening. It’s everyone’s responsibility.

Related Features

A Ret. Bomb Technician Explains Package Bombs and Trip Wires Used in Austin Bombing

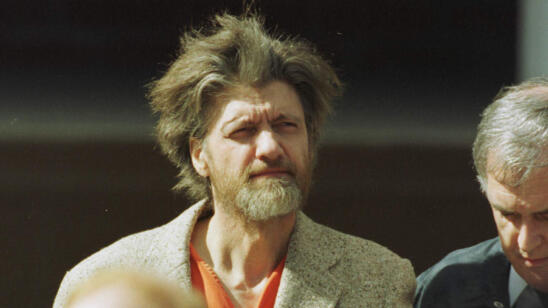

Where Is ‘Unabomber’ Ted Kaczynski Now

Bomb Squad Commander on ‘Pizza Bomber’ Scene Reveals Changes Made in Aftermath