Pamela Everett, a journalist and lawyer, never knew her aunts, who died tragically as children in the 1930s. In fact, Everett hadn’t even known they existed until she was a teenager, when her father, in the heat of anger, blurted out a vague remark about losing his sisters. As an adult with an interest in crime, justice and wrongful conviction, Everett began to research the aunts she’d never known—and uncovered more than she bargained for, as she chronicles in her new book Little Shoes: The Sensational Depression-Era Murders That Became My Family’s Secret. (Read an excerpt.)

In 1937, Melba Marie, 9, and Madeline Everett, 7, were sexually assaulted and strangled, along with their friend Jeanette Stephens, 8, after playing at a local Inglewood, California park. Their little shoes had been lined up neatly in a row, their bodies abandoned in a ravine. The quiet Los Angeles-area community was terrified, and after a frenzied, media-fueled manhunt, the Los Angeles Police Department homed in on the suspect they believed to be their man: Albert Dyer, a mentally challenged crossing guard who worked at the girls’ school..

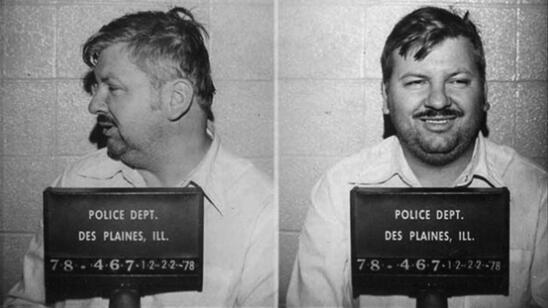

Dyer fit the suspect sketch compiled by witnesses, and he even tepidly confessed to the crimes under police pressure. (He later recanted.) Still, there was no cohesive evidence linking him to the case. Despite this, Dyer was convicted of the murders, becoming the last person sentenced to hang in the state of California. He was executed at San Quentin in 1938.

A&E True Crime spoke with Everett about the murders and what she believes was Dyer’s wrongful conviction.

Why did you decide to tackle this story?

I got into it about 20 years after my dad made that cryptic comment to me. I pursued it as family history.

[Watch episodes of City Confidential in the A&E App.]

In 2008, I moved to Nebraska to take a teaching job, which coincided with me leaving the law. I had a lot more time on my hands and I was learning a lot about wrongful convictions and innocence-exoneration work. I volunteered with the Nebraska Innocence Project, and…got back into the piles of materials in my closet. With this new lens, I started looking at it from that perspective.

Can you talk about the historical relevance of these murders, both in L.A. and in America as a whole?

So many people were flooding to L.A. during the Depression years because there was a little bit of work [there], compared to other places. It attracted a lot of shady characters, quite frankly, and a lot of men who were out of work. There was an upturn in sexual assaults and…homicides against children.

A couple of things also came together in my aunts’ case. They brought in Dr. Paul De River, a psychiatrist who had aligned himself with law enforcement in a lot of informal ways. He [became] a discredited figure because of his involvement in the Black Dahlia case later. But at that time, police were listening. They were looking for any ways to catch…whoever killed my aunts.

De River [created a profile of the killer] before they found Albert Dyer. His profile was considered one of the first in the United States provided for law enforcement to solve a crime. He established a sex-offender bureau within the LAPD shortly after that case, [which] got the wheels turning for sex-offender registration nationwide.

Were you shocked by anything you found in De River’s profile?

No, it sounded plausible. What interested me is in some of his confessions, Albert Dyer said he lined up the shoes, prayed over the bodies and asked for forgiveness for what he had done. Of the little bit I knew about him at the time, this comported with my idea of him as a wretched, sad, tragic case.

What role did the media play in the case?

It was huge, the impact the media had without television. Looking back, the district attorney’s office viewed the media in such powerful ways; they gave a taste of Albert Dyer’s [possibly false] confession. There were little snippets of the confession [that the media ran] and tainted the jury pool far and wide. So many people were exposed to that information. You read those confessions without the lens I have and you think, ‘This is the guy. It has to be.’

How do you think it would have played out differently if Dyer had been tried today, with the same lack of DNA evidence?

The idea of a crossing guard at a school preying on [children] is so terrifying to so many people. And [with] Dyer’s looks–sometimes he looks like a movie star, other times he’s this terrified child–people would have been horrified, but titillated.

It would have been intense in a different way. It would have focused more on him. And there would have also been more of a magnifying glass on police practices. He probably would never have been in an interrogation room [today] without an attorney, given he was mentally challenged.

Your father and grandparents were very reserved with their feelings about your aunts’ murders. Did you talk to any other relatives for the book?

The only living relative I was able to connect with was my dad’s brother, and he was only 5 years old at the time. I delicately floated it one night after dinner: ‘ Can you tell me anything about it?’ But this look on his face was, the look of that 5-year-old boy. … It’s hard to articulate, but he was a big, strong, burly man and I just saw this collapsing and this closing down.

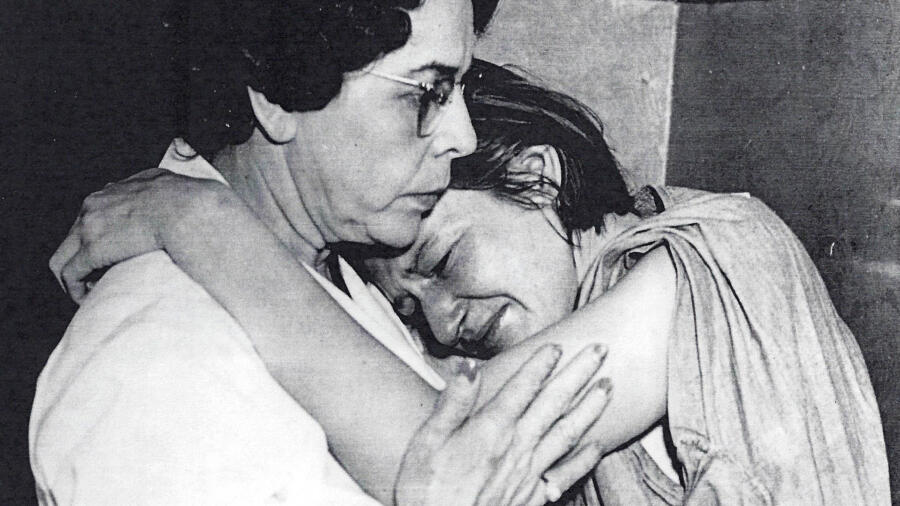

I was able to reach descendants of Albert Dyer’s recently. I tracked down his niece and told her, ‘I’m not sure that your uncle was the person who did these things.’ And she immediately began weeping.

She said, ‘He looked exactly like my mom, who was the most wonderful woman. When you were telling me what he was accused of, I was thinking there is no way someone with the same flesh and blood as my mother would have committed these acts.’

Did you reach a conclusion about who might have killed the girls, if Dyer didn’t?

Fred Godsey is a guy who keeps me up at night: when I read the interview about the friend who… talked about how [Godsey] had bitten a guy’s ear off, how he’d rip apart phone books with his hands, and the truck, the rope and all the evidence of him being in the park that day.

What are some of the inconsistencies in the case against Albert Dyer?

They line up like a laundry list of the hallmarks of wrongful convictions. From the front end, police interrogate him with no attorney. There are gaps in time that aren’t accounted for in [Dyer’s] police custody. And then his confessions themselves read like the types of confessions we know through DNA evidence are false: ‘Yes, sir. No, sir.’ The police are providing the narratives. He is just nodding his head. And even when they let him fix the story a little bit, he’s inconsistent about everything, like how he killed them. Was it slitting their throats, or was it using his hands? Who was first? Where did you go? The sexual assaults, how did they occur? He changes the story more times than he gets it right.

He confessed nine times and he recanted five, and nothing in any of those recantations or confessions is consistent in any way.

Related Features:

Read an Excerpt from ‘Little Shoes’

The 1906 Celebrity Murder That Shocked the World

Over a Century Ago, a Mysterious Axe Murderer Rode the Rails, Chopping Up Families Along the Way