Barbara “Bonnie” Graham and her two co-defendants, Jack Santo and Emmett Perkins, went on trial for murder on August 18, 1953. The victim, Mabel Monahan (also sometimes spelled Monohan), age 64, had been tied up and beaten in her Burbank, California, home on March 9, 1953, before asphyxiating from around her neck. Monahan was targeted due to a mistaken belief that her house contained a safe with a large amount of cash that belonged to her former son-in-law, a mob-connected Las Vegas casino investor.

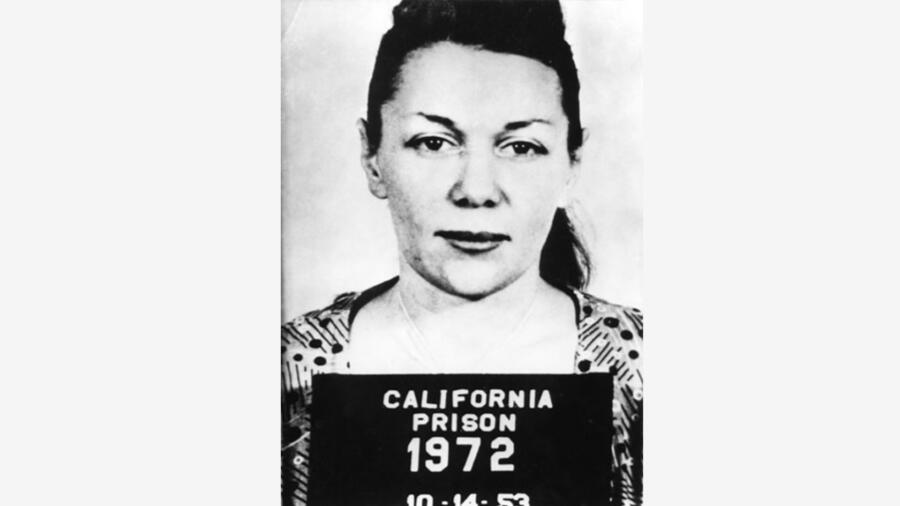

The case was a sensation from the moment Monahan’s body was found. The media particularly focused on Graham, nicknaming her “Bloody Babs” and painting the 30-year-old, whose criminal history consisted of prostitution, bad checks and perjury, as a beautiful, cold-blooded killer.

Two events during the trial seemed to solidify the case against Graham: First, an accomplice who was granted immunity testified that Graham had attacked Monahan before her co-defendants entered the house. And an undercover police officer took the stand to say Graham had asked him for a fake alibi.

In September 1953, the jury found Graham and her co-defendants guilty of first-degree murder. All three received death sentences.

On June 3, 1955, Barbara Graham died in the gas chamber at San Quentin Prison. She was the third woman executed by the state of California. Only one other woman was executed after her.

Now former prosecutor and author Marcia Clark has re-examined this case and learned that the trial leading to Graham’s execution was anything but fair. Clark speaks to A&E True Crime about her book, Trial by Ambush: Murder, Injustice and the Truth About the Case of Barbara Graham.

How did you research events from more than 70 years ago?

I realized very quickly that the real story I needed to tell was the trial. So I thought, How am I going to get my hands on these [trial] transcripts?

I wound up going to the state archives. That was a whole process where they kept saying, ‘We have to make sure that we can release them.’

[Stream Marcia Clark Investigates The First 48 in the A&E app.]

They eventually did [send the transcripts]. When those boxes came, every bit, from pre-trial motions to the final sentence, it was all there.

And I got lucky [with] another source. Hollywood producer Walter Wanger kept a collection of all of his papers. [Note: Wanger produced I Want to Live! (1958), a movie inspired by Graham.] They included an entire file on Barbara Graham’s case.

You learned that the prosecution didn’t give the defense a statement from the accomplice-turned-witness, John True?

Walter Wanger’s file led me to John True’s original statement, which conflicted in some interesting ways with his actual testimony—and was never revealed to the jury.

He was such a key witness. There was no one else who could testify to what actually happened in [Monahan’s] house. For Barbara, in particular, that was critical, because the story [True] told about what she did in the house—her being the one to pistol-whip the victim—was the only testimony that could make that claim.

Even back in 1953, the prosecution should have given this statement to the defense?

Although they didn’t have case law…it was understood that all witness statements have to be produced.

If a statement does exist, especially for a key witness like this, and one that can be seen as contradictory to his testimony, that had to be turned over.

How do you think that affected the outcome of the trial?

It really was literally a matter of life and death.

I think [Barbara] was there [the night of the murder]. She performed her role as the lure [getting the victim to open her door]. [But] I don’t think that she was the one who pistol-whipped Mabel Monahan. I don’t think she ever assaulted the victim.

[True] was lying from the start. Why he chose to nail Barbara, I think, was very simple. It was only he and she who were [initially] in the house, and Mabel had been beaten up for sure. If it wasn’t Barbara, it was him. He wasn’t going to get a deal if he was the one who admitted it.

If [the defense] had been able to undermine his testimony…she wouldn’t have been executed. I feel very confident in saying the jury, had they known what I knew, would never have voted to put her to death.

At trial, an undercover policeman, Sam Sirianni, testified that Barbara offered to pay him for a false alibi for the night of the murder. Donna Prow, a fellow inmate, set up the meeting between Graham and Sirianni while Graham was in jail—but Prow was actually working for the police?

Setting up Donna Prow and using her as an informant to pressure Barbara was a joint action between police and prosecution, as was the use of Sam Sirianni.

Prow got close to Graham in a jailhouse romance?

Yes. That’s another aspect that the jury should have been able to find out: What did Donna Prow do to get Barbara to go along with this false alibi scheme?

Why didn’t the defense have Prow testify about what the police asked her to do?

As soon as Sam Sirianni takes the stand, [the police] took [Prow] out of jail, and, I think, made sure she didn’t have to tell the truth about her whereabouts, because she basically disappeared.

In the system back then, [the court] would appoint lawyers to represent defendants, and then say, ‘Because everybody in the bar owes pro bono services, this is something that you should just do.’ [So defense lawyers back then] don’t have investigators. They can’t afford to pay them. The court won’t pay for them. They’re lucky if the prosecution lends them one of their cops to go and look for a witness, which…when it came time to look for Prow, suddenly they didn’t know what [Barbara’s lawyer] was talking about.

Hiding a witness is, to me, one of the worst things a prosecutor can do.

What kind of impact could Prow’s testimony have had?

I think it would have considerably softened the blow of Sirianni’s testimony, had they been able to reach Prow. It sounds a lot different if what’s happened is Prow is pushing Barbara to [pay for a fake alibi], and Barbara is reluctantly going along with it out of desperation. But when [the defense] couldn’t find Prow, they had nowhere to go with it.

Did you come to any conclusions about why the prosecution behaved like this?

Someone like Barbara, who is beautiful, and you don’t expect her to get sentenced to death, that is [a] big get. I think that notch in the belt was part of the motivation.

You do want prosecutors to present a strong case, and you want them to present the evidence to convict the guilty. That is their job. But it is not their job to hide witnesses, to hide evidence in order to get a conviction—let alone the death penalty.

Related Features:

What’s It Like to Be Executed in the United States?

Cooking Up the Last Meals of Death Row’s Most Notorious Killers

How Lisa Montgomery Spent Years on Death Row Rebuilding Her Life