After subjecting his family to three days of terror in February 1987, Mary Bailey’s abusive stepfather, Wayne Wyers, fell into a drunken sleep.

His wife, Priscilla Wyers, turned to her 11-year-old daughter and uttered six cataclysmic words. “‘I need you to shoot him,” she said.

For Priscilla Wyers, it was an opportunity to escape from the brutish man who vowed to kill her—without being the one pulling the trigger.

For Bailey, it was a horrific turning point that tore her from everyone she loved.

But, “I certainly didn’t feel like I had a choice,” Bailey tells A&E True Crime.

‘Good Country Folk’

Priscilla Wyers was 16 when she gave birth to Mary Bailey, who was raised by her grandparents in West Virginia.

“I had two people that I felt cared very much about me,” says Bailey. “Good country folk.”

Her grandmother made cornbread, gardened and “stole my heart,” Bailey writes in her autobiographical book My Mother’s Soldier.

Her grandfather, a retired coal miner, called, her “princess.” He succumbed to black lung disease in 1981, but she and her grandmother kept living together for several years until Priscilla Wyers begged her mother to move in to help with paying the bills and caring for her other children.

“I never wanted to live with them,” Bailey says. Occasional stays with Priscilla and Wayne showed a “completely flip-side of life,” a violent, chaotic environment that contrasted with her peaceful upbringing.

But her grandmother couldn’t say no to Priscilla.

House of Horrors

Wayne Wyers made no secret of his contempt for Mary. “I was literally the red-headed stepchild,” she recalls.

Along with physical beatings with belts and switches, Mary and her siblings often went hungry at their home in rural Upshur County.

When Bailey’s brother ate a forbidden can of potted meat, Wayne Wyers went on a rampage to find the culprits, she recalls. He took a rat trap, pulled the hammer back and stuck her hand in.

“He told me if I didn’t admit it—he was going to chop every finger off, one at a time.”

Her mother offered no protection.

“One of the worst beatings I got was from her,” Bailey says. “My baby brother was crying and she said: ‘Just leave him alone. Let him cry.’

“I said, ‘he just wants me to hold him.'”

At that point, Priscilla Wyers grabbed a belt. “She swung it buckle-end. It hit my cheek bone and it broke,” Bailey says.

One positive in her life was a local pastor who took Mary to church and became a father figure.

“It’s almost as if God sent him there to help me through this,” she recalls. “Without that faith, I don’t know what I would have done.”

Geographic isolation and inadequate social services make rural women more vulnerable to domestic abuse, West Virginia University sociology professor Dr. Walter DeKeseredy tells A&E True Crime.

“Rural women are at a higher risk of experiencing violence than urban and suburban women,” he explains.

But it’s unusual for a mother to pressure a young female child into retribution, the director of WVU’s Research Center on Violence notes. A more typical scenario is a teenage boy who takes the initiative to defend his mother.

“That house for the mother and the daughter and the others was a house of horrors,” DeKeseredy says.

‘Don’t Make Me Do This’

The violence came to a head on February 24, 1987. While Wayne Wyers was on a trucking job, Priscilla lent his vehicle to a friend, who crashed it on an icy road.

An enraged Wayne Wyers beat his wife repeatedly over several days and when Bailey’s grandmother remonstrated, he slapped the side of her head, causing irreversible hearing loss to her left ear.

Wyers also threatened his infant son.

“The baby’s crying and it’s scary and he’s got a knife,” Bailey recalls. “‘I’m going to watch this man murder my brother,'” she recalls.

Just before passing out, Wyers warned his wife: “‘I’m going to kill you.'”

Shortly after, Priscilla Wyers gave her daughter a gun and the fateful order.

“‘Please, don’t make me do this,'” Bailey remembers pleading. Her mother said: “‘You have to, Mary. He’s going to kill me. And if he kills me—what are you going to do?'”

Terrified, Bailey put the gun up to Wyers’ chest and pulled the trigger. Excruciatingly, it didn’t fire. Wyers checked the weapon and sent her daughter back. Again nothing happened and Wyers realized the safety was on. “‘It’ll work this time,'” she promised.

“That walk back down the hall to the living room was the longest walk of my life,” Bailey says. “When I pulled the trigger, it fired, and fire itself looked like it came out of the end of the gun because it was dark in the room.”

Priscilla Wyers called 911, and Bailey fled to her grandmother’s arms. The solace was brief.

Emergency responders rushed Wayne Wyers to hospital, where he died.

A television news crew showed up, and Bailey says Priscilla Wyers insisted Bailey tell them what happened. “It was her way of putting the blame on me,” Bailey says.

Mother and daughter were both charged with murder, but prosecutors dropped the charges against Bailey. She was a witness at the trial of Priscilla Wyers, who was convicted in 1988.

Asked how a mother could compromise her young daughter in such a way, clinical psychologist Dr. Juanita Guerra tells A&E True Crime that Wyers put the gun in the hands of her 11-year-old “because she was terrified. She was petrified. She was overwhelmed, and literally out of her mind. Because when you are struggling with trauma, there is no way that you can make a good decision.

“When you reach that point, it really is about survival. Never mind about what’s right and wrong,'” says Guerra, an abuse and trauma expert. Instead, it’s “‘we’re going to figure this out, and we’re going to live another day, and we’re going to handle the consequences.'”

Finding a Way

Bailey was placed in foster care after the shooting and never saw her grandmother again.

Although grateful to her foster families, she faults a system that severed her from her relatives at age 11.

“I left the foster care system at 17 with no real sense of family,” she wrote in her book.

Bailey excelled at sports and was awarded a college scholarship, but without guidance and support, she dropped out.

Wyers reached out in 1998 and implored her daughter to testify on her behalf at a parole hearing. Bailey agreed, and told the parole board, “I would like to have my mother back.”

Wyers was subsequently released and Bailey helped her readjust, only to be disheartened by her mother’s reckless behavior.

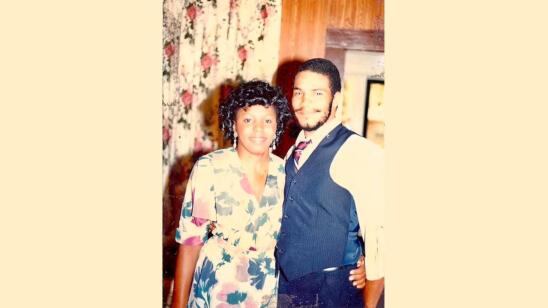

Eager for a fresh start and distance, she moved to North Carolina, returned to college, and married. Now Bailey and her husband run a successful uniform supply business.

After her book was published in 2020, Bailey received a letter from Wyers.

She wrote, “‘I wanted you to know that you were loved … I’m sorry.'”

For Bailey, “it healed me so much.” She called her mother and said, “I forgive you.” She and Wyers reunited in person in 2022.

They spent their first ever Mother’s Day together in May 2022. It turned out to be timely; Wyers had cancer and died that August.

“It feels like it was all just meant to be,” Bailey says. Now she hopes her crucible of violence and pain can give others hope.

“It doesn’t mean it goes away. But we heal, and we move forward, and that’s what we do.” For help with or information about domestic abuse, contact the National Domestic Violence Hotline at (800) 799-SAFE (7233).

Lifetime’s movie, Would You Kill for Me? The Mary Bailey Story, is based on true events and is available to stream now.

Related Features:

Is There a Minimum Age for Being a Murderer?

The Offenders Behind 3 Court Cases That Changed Lifetime Imprisonment Laws for Juveniles

How Faye Yager Operated Her ‘Children of the Underground’ Network