One night in her second year of captivity, 12-year-old Natascha Kampusch woke up in a cold sweat. The basement where abductor Wolfgang Priklopil had imprisoned her was in utter darkness.

“The feeling of loneliness hit me so hard that I was afraid of losing my grip,” Kampusch wrote in her 2011 autobiography, 3,096 Days in Captivity.

Then, she imagined the adult Natascha taking her hand.

“‘Right now, you cannot escape. You are still too small,'” her older self said.

“‘But when you turn 18, I will overpower the kidnapper and free you from your prison. I won’t leave you alone.'”

That pact and sheer strength of will allowed Kampusch to survive six more years of misery.

‘What Could Happen?’

Kampusch’s early years in Austria were far from idyllic. Her parents’ divorce left her insecure and unanchored. A no-nonsense mother thought nothing of slapping Kampusch to discipline her and believed in keeping “a stiff upper lip,” she wrote.

Her affable but irresponsible father would bring his young daughter to bars and stay up late drinking with friends.

That turbulent childhood likely caused Kampusch to grow up quickly in terms of learning to navigate difficult situations, forensic psychologist and author Joni Johnston tells A&E True Crime.

“She struck me as somebody who was 12 going on 25. Somebody who was pseudo-mature, meaning their survival skills are older than their chronological age. In some respects, that probably served her well,” Johnston says.

On March 1, 1998, Kampusch’s mother became enraged when her father returned her late from a visit.

“‘You are not to see your father anymore!'” she ordered.

The next day, the 10-year-old left for school without saying goodbye. “‘After all, what could happen?'” she thought.

‘I Would Probably Die’

Several blocks from Kampusch’s home outside of Vienna, she saw a man standing near a delivery van. He looked out of place, and she felt uneasy. As she walked by, he seized her by the waist and tossed her in the van.

“‘I had been kidnapped and…I would probably die,'” Kampusch thought. But amid her terror, she reasoned that communicating with the kidnapper could keep her alive.

First, Kampusch asked Priklopil what his shoe size was. Then, “‘Are you going to molest me?'”

“‘No, you’re too young for that,'” he answered.

At his home, Priklopil carried the child to a secret basement room with a concrete door.

Kampusch panicked but realized pleading would be futile. Instead, “I felt I had to accept the situation in order to get through this one endless night in the cellar,” she wrote.

Priklopil was alternately paranoid—confiscating her school bag because he thought she’d hidden a transmitter inside, and fatherly—reading a fairy tale before bestowing a goodnight kiss.

It comforted Kampusch until the door shut and “the protective illusion burst like a bubble.”

Call Me ‘Maestro’

Initially, Priklopil could be kind. He brought Kampusch a computer, multiple books and surprised her with chocolate eggs their first Easter.

He also lied to Kampusch that day, saying her parents never paid a ransom and didn’t love her. He added: “‘You’ve seen my face. Now I can never let you go.'”

Quickly, Priklopil took control of every facet of her life, turning the electricity off at 8 p.m. every night and barking orders on an intercom like: “‘Have you brushed your teeth?'”

At one point, he demanded to be called “Maestro,” which she refused.

But despite the horrific treatment, Kampusch never dehumanized her captor.

“Had I met him only with hatred, that hatred would have eaten me up and robbed me of the strength I needed to make it through,” she wrote.

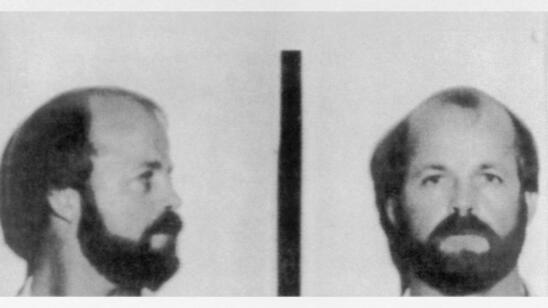

An Inconspicuous Man

Priklopil grew up in a well-to-do family and was close to his mother, Kampusch wrote. A communications technician, he lost his job and drifted into renovating homes with a man named Ernst Holzapfel, whom she characterized as his only friend.

Outwardly, he was inconspicuous, reserved, neatly dressed. But dueling passions raged inside: the need for control and for affection.

Johnston thinks in snatching Kampusch, “it was the ultimate narcissism—to think it’s OK for you to kidnap a child off the street.”

But asked if Priklopil was insane, “clearly this is somebody who knows the difference between right and wrong, by building a room and by hiding her,” Johnston explains.

Starvation, Violence and Cuddling

When Kampusch entered puberty, Priklopil dropped his paternal facade, forcing her to clean and help renovate his house. Once, he threw a sack of cement at her. “I felt like a battered dog, who is not allowed to bite the hand that beats him because it is the same hand that feeds him,” she wrote.

Priklopil was already verbally abusing Kampusch, and that incident triggered continuous kicks, punches and other violence.

She recalled Priklopil randomly stabbing her knee. As she bled, he bellowed, “‘You’re making a stain!'”

Another terrifying memory was Priklopil taking to her to his bed and tying their wrists together. Kampusch feared rape, but instead “the man who beat me…wanted to cuddle.”

That changed as she got older.

She was also malnourished, subsisting on tiny meals, while he ate heartily. And when Kampusch dared to sass Priklopil once, he locked her in the basement for several days without food. Eventually, he threw her some carrots. “‘Are you going to be good now?'” he asked.

Rebellion

Kampusch began fighting back at age 15. When she punched Priklopil, he put her in a headlock, but “I proved to myself that I was strong and hadn’t lost my self-respect,” she wrote.

Around this time, Priklopil began taking her out—on skiing trips, shopping and to work sites, albeit with threats to keep quiet.

But she felt paralyzed to escape or ask for help.

The paralysis was a natural reaction to years of brainwashing, Johnston says.

“When you’re scared of somebody and physically abused…and she probably doesn’t know where her parents are—it’s almost unrealistic to think the first time you’re out with this person, you start screaming.”

The day she turned 18, Kampusch found new courage. “‘This situation must come to an end,'” she told Priklopil. “‘One of us has to die, there is no way out anymore.'”

On August 23, 2006, Kampusch was vacuuming Priklopil’s car. He took a phone call and stepped away. For the first time since 1998, she was outside and alone.

“Run. Run. Damn it, run!” she told herself.

She raced through the open gate. Several neighbors were suspicious of the frantic woman, but one homeowner called police.

The next day she learned Priklopil had thrown himself in front of a train and died. “It was over,” she wrote. “I was free.”

Kampusch reunited with her family and is now an author and sponsors charitable projects.

Can Victims’ Ordeals Help Others?

Criminologist Stephen Jones tells A&E True Crime he isn’t surprised Priklopil committed suicide rather than fleeing.

Kampusch filled many roles in his fantasy life, from daughter to girlfriend to spouse, Jones says.

“In the end, I think he thought he had done everything he could for her. And I really think he felt betrayed, which is why he laid down on the railway tracks and got decapitated by a train,” explains Jones, a veteran police detective sergeant and adjunct college professor.

Most child abductions are committed by family members, and it’s extremely rare that a stranger kidnaps a minor with the intent of keeping them, the Crimes Against Children Research Center reports.

Jones compares Kampusch to two other outliers—kidnapping survivors Jaycee Dugard and Elizabeth Smart.

Not only did the three women endure months of torture but mistakes occurred during the separate investigations. Police interviewed Priklopil at his house and received a detailed tip pointing to his culpability—yet believed he was harmless.

“In all three of these situations, you see the missed opportunities,” Jones says. But by analyzing these crimes, “maybe we can limit these kinds of cases by discovering the flaws in investigations or what was missed.”

Related Features:

Why Some People Hold Others Captive

Colleen Stan Was Kidnapped and Kept in a Box for 7 Years

Elizabeth Shoaf Was Kidnapped and Assaulted Inside a Bunker for 10 Days: How the Teen Escaped