In 1965, Oneal Moore, one of the first two Black deputy sheriffs in Louisiana’s Washington Parish, was shot in a drive-by ambush while on patrol with his partner, Creed Rogers. The murder sparked an FBI investigation that spanned more than five decades. But while there was no secret about the identity of the prime suspects—all of whom were members of the Ku Klux Klan—no one has ever been charged in the crime.

Author Stanley Nelson explores the case in his book Klan of Devils: The Murder of a Black Louisiana Deputy Sheriff.

A finalist for the 2011 Pulitzer Prize in local reporting, Nelson spoke with A&E True Crime about what led to Moore’s killing and why no justice has been served.

It takes a special kind of brazenness to kill a police officer. What exactly led to the murder of Oneal Moore?

During the 1960 and 1964 elections for sheriff in Washington Parish, the Klan ran its own candidate against Sheriff Dorman Crowe. They used various tactics to try to beat him, but came up short both times. The Klan wanted its own man in office to preserve segregation.

When Sheriff Crowe was seeking reelection in 1964, he once again sought support from the Black community and promised that if reelected, he would hire two Black deputies. When he was re-elected, he kept his promise and hired Oneal Moore and Creed Rogers, the first two Black deputies in the history of the parish.

The Klan was furious and vowed revenge. In the Klaverns (local branches) throughout the parish, there was talk on what to do about the deputies. That led to the Klan ambushing Moore and Rogers exactly a year and a day after the two deputies began their jobs. [Moore was killed instantly in the shooting; Rogers was injured and lost an eye].

To the Klan, it was an insult for a Black man to have the ability to arrest a white man—or worse, a white woman. It was the ultimate insult: that a Black man would have the power of the law behind him.

The culprits were protected by the culture of silence and fear surrounding the Klan in Louisiana in the 1960s. Why did the Klan have such a stronghold on the area?

Because most white people supported segregation wholeheartedly, the Klan offered an opportunity to preserve it. The Klan presented itself as a Christian organization that had to do certain things to support segregation. So many white people just looked away. But also, the Klan was made up of brutal men. Some had criminal records. Everyone feared them.

One suspect in Moore’s murder was Elmo Breland, who a few years later was convicted in the murder of a white man in Bogalusa [Louisiana]. The Klan also beat and whipped white men who Klansmen felt weren’t holding down a job or were drinking too much. If you talked bad about the Klan, they usually found out and you’d have a cross burned in your yard or you might be attacked.

Klansmen wore hoods at certain public events, and they usually covered their faces on wrecking crew projects [violent actions undertaken by secret Klan hit squads], making the attacks even more horrific. The ‘invisible empire’ invoked fear in anyone, including other Klansmen.

A Bogalusa white woman’s husband had been kidnapped and beaten by the Klan. She later told the newspaper in Bogalusa, ‘I used to think maybe there was some good to the Ku Klux Klan, but they’re nothing but a pack of no-good devils.’ That’s what they were.

You obtained almost 40,000 pages of FBI and Department of Justice investigation documents pertaining to the Moore case. What were some of the biggest discoveries?

It is always a thrill to see an FBI document that hasn’t been read since it was filed away decades ago. Finding detailed reports on suspects, on-the-scene facts about the investigation and multiple other events is incredible.

For instance, the FBI attempted to recreate the ambush with Rogers on the scene, but a crowd of onlookers showed up and the FBI had to cancel the recreation. A cop in Bogalusa had tipped off the lawyer for the lead suspect, [Klansman] Ernest Ray McElveen, and word got out. This led to an FBI investigation as to who tipped off the lawyer. The FBI learned that the tipster was Bogalusa Police Chief Claxton Knight. Lots of tidbits like this in the documents.

You describe the FBI’s investigation as ‘creative.’ What do you mean by that?

Not only did agents do their usual surveillance and questioning of suspects and eyewitnesses, but the bureau also obtained phone records of Klansmen and wired informants—on and off for decades. Their surveillance efforts were nonstop once an investigation of a subject began.

Two men confessed, on tape, to the murder. Why would that not be enough to charge them?

Even with a confession, if the FBI could not find corroborating evidence, such as a murder weapon, the Department of Justice (DOJ) felt that without solid supporting evidence, a defense attorney could cast reasonable doubt on a prosecution.

The DOJ’s case closure letter noted: ‘This laundry list of alleged perpetrators demonstrates the virtual impossibility of prosecuting this case even if someone were to confess to the crime.’ Of course, without taking such a case to court, we will never know whether someone could have been convicted.

There was a latent print found on the pickup truck of one of the alleged Klansmen conspirators. Was that useful in any way? Was the technology at the time good enough?

The fingerprint technology then was as good as it is now. The problem for the past five decades was that they could never match the print to a person. But the technology today would have made a big difference. Back then, there were no cell phones that could be tracked and no GPS on vehicles.

What led to the investigation reopening again in 1990, 2001 and 2007?

New tips. And to the credit of the FBI, the bureau followed every tip as far as they could take it.

The FBI and DOJ investigated the case over the course of 51 years, from 1965 to 2016. Would it be fair to question the competence of the investigators? Were any stones left unturned?

It was a thorough investigation, in my view. The FBI pounds the pavement and investigates, but they don’t prosecute. Ultimately, the DOJ determined it couldn’t prosecute anyone. As the book notes repeatedly, there were some very strong confessions and circumstantial evidence.

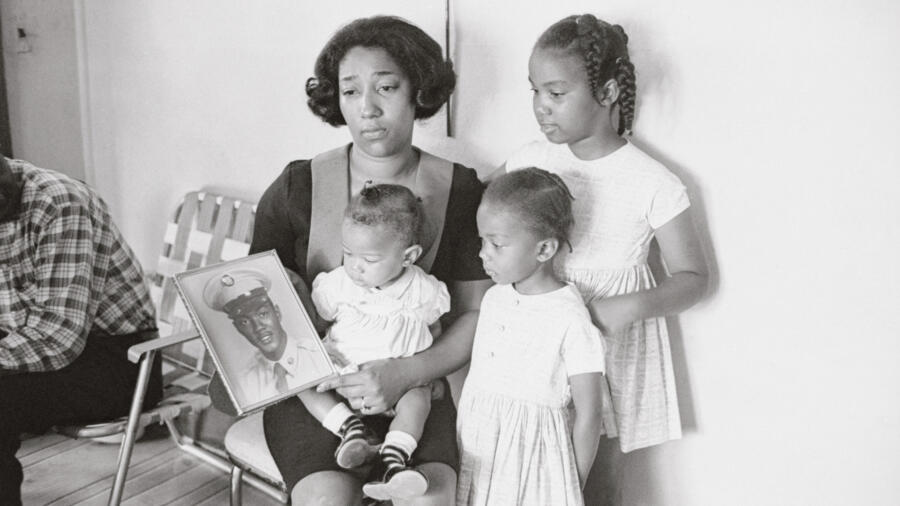

What toll did the unsolved murder take on Moore’s family, his surviving partner, Creed Rogers, and the larger Black community in Washington Parish?

For the families, it causes pain and suffering—and that never really goes away. There is a sense of loss, and you feel as if you are on an island all by yourself and that nobody understands your situation. And that’s true.

For Creed Rogers [who retired as captain for the sheriff’s department in 1988 and died in 2007], I think he felt some degree of survivor’s guilt. The deputies rode in the same patrol car, and the week the two deputies were attacked, it was Moore’s turn to drive. Rogers was seriously injured physically, but he also suffered emotionally.

His and Moore’s relationship was unique—they were civil rights pioneers in Washington Parish as the first two Black deputies. Plus, Rogers was a hero—had he not quickly radioed in the attack and described the pickup truck [noting there was a Confederate flag on it], McElveen would never have been arrested an hour later in Mississippi.

For the Black community, this is another case of no justice. When the FBI reopened the case in the 1990s, agents got an earful. The bureau noted that the Black community believed ‘the entire investigation was a coverup. The Black community feels cheated, and they feel the law enforcement, including the FBI, cannot be trusted.’

Related Features:

FBI Profiler John Douglas on the Racist Rampage of Joseph Paul Franklin

What Are Some of the Oldest Cold Cases That Have Recently Been Cracked Open?