In the early 1980s, two paperboys from the sleepy Iowa capital played a critical part in helping shape the era of missing and abducted children.

On September 5, 1982, 12-year-old Johnny Gosch left his house in the suburb of West Des Moines, Iowa, with a canvas delivery bag, red wagon and his dog, Gretchen, shortly after 5:45 a.m. to deliver Sunday editions of the Des Moines Register. Around 6 a.m., Johnny arrived at a street corner where a delivery van dropped off bundles of newspapers, and he and another paperboy began to sort and fold them. After giving directions to a passing motorist, the boys separated on their respective routes. Minutes later, though, the boy spotted Johnny just a block away, talking to a man, but couldn’t tell in the pre-dawn dimness if it was the same man who’d asked for directions. Because neither Johnny nor his dog appeared distressed, the boy continued his route.

An hour and a half later, a customer telephoned Johnny’s house wanting to know where his paper was. Concerned, Johnny’s father, John, Sr. went looking for his son and quickly discovered Johnny’s red wagon, still full of papers, abandoned at a corner on his route. Gretchen, meanwhile, had returned home alone. Around 8:30 a.m., Johnny’s mother, Noreen, called the police.

In 1982, many law enforcement agencies across the U.S. still observed a 24-to-72-hour mandatory waiting period before filing a missing person’s report, even for a minor, and often treated missing adolescent cases as runaways. Johnny’s case was no exception.

According to Noreen in the 2014 documentary Who Took Johnny?, officers from the West Des Moines Police Department didn’t arrive until some 45 minutes after the Gosch’s initial call, and during their interview asked, “Has your son ever run away before?” Eventually, an estimated 30 officers were summoned by that afternoon to help friends and neighbors search for Johnny, but the WDMPD and Department of Criminal Investigation were reluctant to involve the FBI, telling the Gosches, “We do not consider Johnny to be in danger, until you (his parents) prove his life is in danger.”

The case quickly went cold.

Parents Turned Activists

A month after Johnny’s disappearance, with no leads or suspects, Noreen and John formally launched The Johnny Gosch Foundation to help fund private searches for Johnny and to share child safety information through their “In Defense of Children” program.

In June of 1984, they and other parents of high-profile missing children helped establish The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC). That same year, the Gosches also authored and lobbied for “The Johnny Gosch Bill” in Iowa, which mandated immediate police response and involvement when a child was reported missing. Later adopted by eight additional states, it was signed into Iowa law on July 1, 1984.

Just 43 days later, The Johnny Gosch Law would be put to the test.

A Second Boy Disappears

On the morning of August 12, 1984, 13-year-old Eugene Martin left his house in a South Side Des Moines neighborhood around 5 a.m. to deliver Sunday editions of The Des Moines Register. He arrived at his pickup corner around 5:15 a.m., collected his bundles from the delivery van driver, and sat down to start folding them. According to Register stories, several passing witnesses reported seeing Eugene talking to a man in what looked to be a “friendly” conversation as he filled his delivery bag.

Forty-five minutes later, a woman called Eugene’s route manager saying she hadn’t received her paper yet. Thinking Eugene had overslept, the route manager went to the corner and was surprised to find Eugene’s delivery bag with 10 rolled papers inside, but no Eugene. After delivering the papers himself, the manager went to the Martin house to speak with Eugene’s father, Don. When Don realized Eugene hadn’t returned home, he started searching the neighborhood, but found no sign of his son. He called the police around 8:40 a.m.

Learning from the Gosch case in WDM, a different jurisdiction, the Des Moines Police Department responded immediately by sending out all-points bulletins (APBs), setting up roadblocks, canvassing neighborhoods within the hour and involving the FBI by that afternoon.

Officer James Rowley, now retired, was one of the first DMPD officers on the scene. He recalls how “a lot of shoe leather went into the canvasses,” because his then-lieutenant didn’t want “another West Des Moines deal” with a “botched” investigation.

During the height of the Martin investigation, Rowley traveled as far as Mexico and Canada to follow up on tips, and estimated he chased down “somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 leads,” but none was credible. “There’s never been a solid lead, a bone found, a fragment found,” Rowley tells A&E True Crime “We didn’t turn up any evidence.”

Like Johnny’s case, Eugene’s went cold. Authorities were never able to formally connect the two cases.

Community, State and National Search Efforts

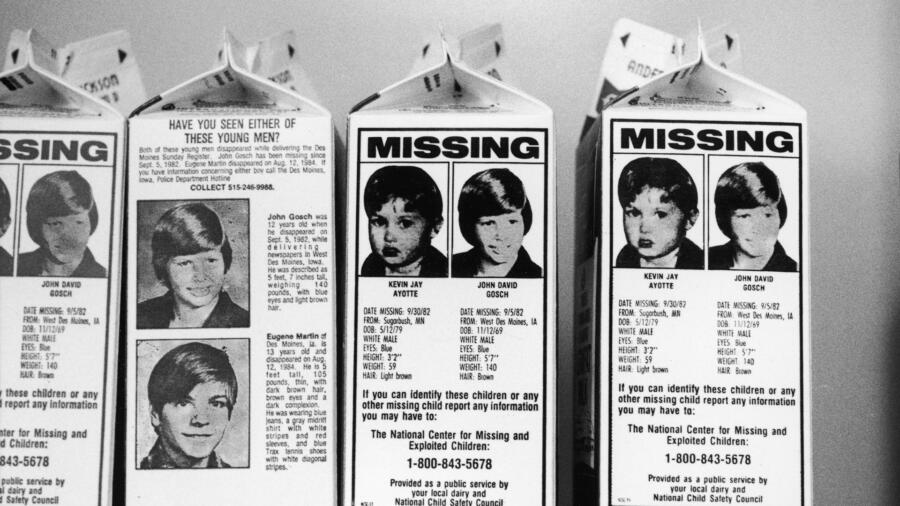

Weeks after Eugene’s disappearance, a local Des Moines grocery store started printing reward info with Eugene and Johnny’s missing pictures on their paper bags. Soon after, a Des Moines milk company, Anderson Erikson Dairy, started printing pictures and short bios of both Eugene and Johnny on the sides of their half-gallon milk cartons after an employee and friend of the Martin family suggested it. The following week, another Des Moines dairy company followed suit. From there, the campaign spread to dairy companies in Illinois and California, and by January of 1985, the National Child Safety Council began a nationwide “Missing Children Milk Carton Program,” featuring hundreds of missing children’s pictures on milk cartons.

In a 2019 A&E True Crime interview, Angeline Hartmann of the NCMEC stated that the single most productive or helpful element of finding missing kids is publicly sharing a current picture of the child.

By the late ’80s, though, the milk carton program was phased out when paper cartons were replaced by plastic jugs, and after it proved only marginally successful in helping to locate missing children because of slow photo distribution. It did, however, serve as an important precursor to the more effective Amber Alert system, which helps law enforcement agencies and media outlets distribute news of child abductions almost immediately.

In August 1984, the Goshes traveled to Washington D.C. to testify before Congress during hearings on organized child crimes; and in May 1985, they again spoke at Senate subcommittee hearings on missing children issues. In that testimony, Noreen and John notably lobbied for the development of a specially trained task force to deal with cases of missing children. By 1987, the U.S. Department of Justice developed an “Investigator’s Guide to Missing Child Cases For Law-Enforcement Officers Locating Missing Children,” which included uniform protocols for initial responses, and information on how to use the newly-formed National Crime Information Center database record entry.

Today, Johnny Gosch and Eugene Martin have been missing for over 40 years. Both cases are still technically open in the West Des Moines and Des Moines police departments, and even though neither boy has been legally declared dead, both are presumed dead by authorities. Martin’s parents died nearly two decades ago believing their son likely died shortly after his disappearance, but Noreen Gosch still holds onto hope that she’ll one day have the answers about her son’s fate. While most people outside of Iowa have probably never heard of these two missing kids from a small Midwestern city, they have played critical roles in shaping missing children investigations today.

Related Features:

What Drives Some People to Kidnap Children?

Live PD’s Angeline Hartmann on Jayme Closs and Misconceptions About Missing Children Cases