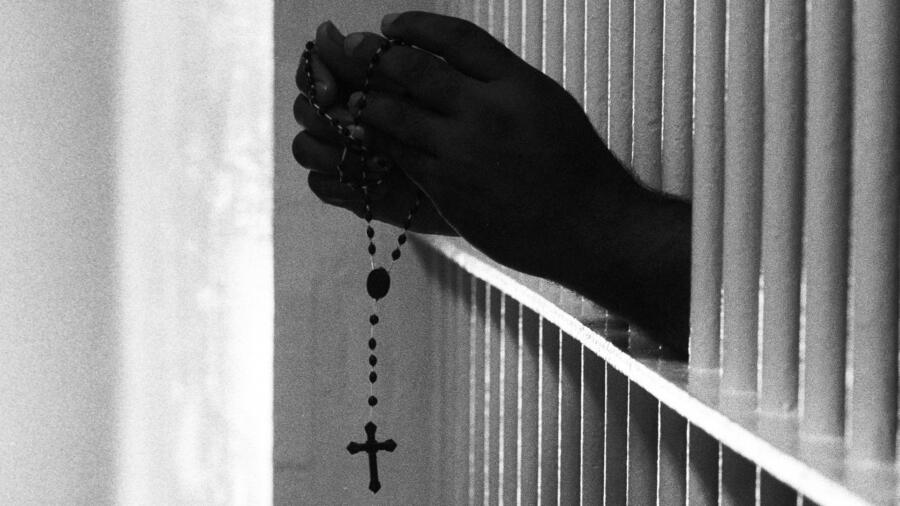

What’s it like to minister to criminals who society identifies as the worst of the worst?

The primary duty of a Christian prison chaplain is to serve the spiritual and emotional needs of those who self-identify as Christian or who are interested in the faith. While there are chaplains of all faiths within the U.S. prison system, by and large Christian clergy members comprise the vast majority of the chaplaincy, according to a 2012 survey of prison chaplains by the Pew Research Center.

From 1990 to 1996, Richard Lopez, a Catholic, served as the prison chaplain at the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville, where he ministered to the state’s death-row population. He spoke with A&E True Crime about how murderers on death row come to embrace a higher power while awaiting execution.

From your experience, how would death-row prisoners turn to religion? Did you find any of the inmates resistant to it?

There were some. I would walk down the aisle in front of their cells and say, “Hello, how are you doing?” And some would say, “I have no use for God in my life.” But through time, as I would [pass by] their cells…some of those men who completely turned me away at first would say, “Chaplain, it’s okay if you want to stop here and talk to me.”

But not all of them.

I would never judge those who didn’t. Many of them were raised without parents, without any love, without any discipline. They never knew anything about God.

Did you ever find some of those resisting would ultimately embrace Christianity in their final hours?

It did happen. Being with them in the death house, many times the afternoon they were scheduled [for execution], we would connect. I would listen to them. I would always wear a watch and I’d say, “You have six hours left, is there anything you want to talk about? Many of them wanted to know about God. That’s when I had the opportunity to minister to them on God’s forgiveness.

I’d say, “I hear your story. I want you to think about three things. One: Admit you did wrong. Two: Repent. Three: Ask God for forgiveness. Those three things allowed them to move forward and prepared them.

That would happen even in the last 30 minutes before an execution. There were some [who] in the last 30 minutes, surrendered.

What about the other way? Any prisoners who dabbled in religion but then backed away as their hour drew near?

Oh, no. I do not remember one individual there who did that.

There were a few men who—even up until their last minutes before execution—did not want to hear about God…maybe only two in my whole time [there].

What was the biggest challenge for you in getting those on death row to embrace Christianity?

The biggest challenge I heard and felt was that they could not accept or believe that God would forgive them for the crime they committed, for what they did. That was a huge wall for them to get through.

Others went through all of that years before an execution. Many of them were ready to leave this world and were at peace because they felt God’s forgiveness.

Did you do your own research into the crimes of the men and women you were ministering to?

I never looked. Even now I haven’t looked at the individual’s crime on the record. But as we grew in this God-centered relationship…they would mostly tell me their crime.

Do you think there’s something about being on death row that inspires prisoners to turn to faith more than they would if, say, they were sentenced to life imprisonment?

I don’t think there’s a relationship between the two. They connected with God—knowing that they were on death row—but through the courts they were still going to exhaust all possibilities. Then, as time moved on, they knew there was going to be a day when they would be executed. They would work [harder] to build a positive relationship with God to get rid of the negative of their path.

Did you find that the nature of a murder had any impact on whether or not a killer would embrace God while waiting out their sentence? After all, crimes of passion and cold-blooded killing seem like fundamentally different things.

That is a tough question. Many of them were after something.

For most of them who committed a horrible crime, they were not in their right senses: They were high on drugs or high on passion. They didn’t know what they had done until days or months after. But none of them were connected to the love of God or the forgiveness of God. That’s what would’ve [kept] them from going down that road.

Related Features:

How Police Chaplains Help First Responders During (and After) Tragedies

Got a Parent in Prison? This Drug Lord’s Son Wants to Help

Dogs Behind Bars: What Inmates Get From Training Service Animals