The area in and around Galveston County, Texas was a scary place to be for young women in the 1970s. Eleven teenagers—Colette Anise Wilson, Brenda Jones, Rhonda “Renee” Johnson, Sharon Shaw, Debbie Ackerman, Maria Johnson, Gloria Gonzales, Kimberly Rae Pitchford, Georgia Geer, Brooks Bracewell and Suzie Bowers—were brutally murdered throughout that time, some of them in pairs. Their murders were never solved.

In A&E’s series The Eleven, journalist Lise Olsen and retired Galveston Police Department detective Fred Paige revisit the cold cases after they are presented with a confession letter from inmate Edward Harold Bell, who is serving a 70-year-sentence for a different murder. Although in exclusive in-person interviews with the investigators, Bell denies the written confession, the series details the additional circumstantial evidence they hope will prove his guilt.

[Watch all episodes of The Eleven here.]

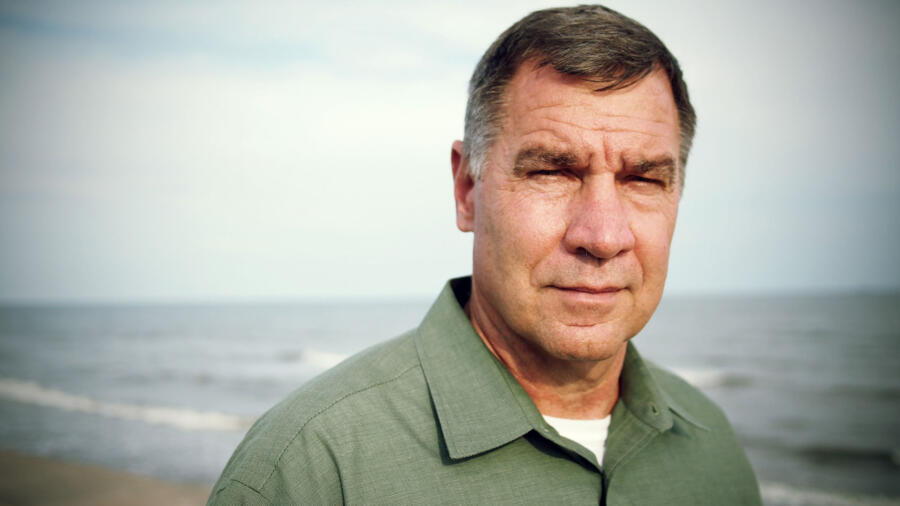

A&E True Crime spoke with Paige about why the murders have gone unsolved for so long, the common thread among family members of the victims and his hope for Bell’s upcoming parole hearing.

You started working for the Galveston County Police Department in 1988. Had you ever worked on any possible serial killer cases before this one?

Yeah, but a different type of serial killer. It’s still an open case. There was one suspect and, in my opinion, he murdered an individual in an armed robbery. I believe he was involved in at least two other murders in and around Galveston County.

[Watch The Eleven on A&E Crime Central.]

I’ve looked at several cases involving two murders and a lot of single murders, but a serial killer is [involved with] three or more murders.

What do you believe is the single strongest piece of evidence linking Ed Bell to the murders of the 11 young women?

No doubt, it’s his confession letter. But you also have a lot of circumstantial evidence around that confession letter, which is what the show’s going to be about.

[In 1971] two 16-year-old girls saw [two of the victims] Debbie Ackerman and Maria Johnson get in a vehicle, and they described that vehicle perfectly in a police report. They didn’t have the license plate, but the suspect was arrested in the same vehicle three months later in Louisiana after an [indecent exposure] episode.

Then you have an eyewitness account of a girl who actually survives an assault by Ed Bell. And there’s a lot more.

Before Ed Bell’s confession letter recently came to light, had anyone ever made a connection between any of the 11 unsolved murders?

We did some research in the show about that. In 1981 [former Brazoria County Sheriff Lt.] Matt Wingo talks about linkage. He thought the same killer was responsible for a lot of these murders.

If you go back to January 1972, there is a Houston Post article where the chief deputy of Harris County talks about the murders of Gloria Gonzalez, whose skeletal remains were found at Addicks Dam [in Houston], with [skeletal remains of] another victim, Colette Wilson, who’d gone missing in June 1971. Gloria went missing in October 1971.

In the article Frazier also stated that Gloria Gonzalez was linked to a surf club in Galveston, and then he makes an affirmative link to Debbie Ackerman and Maria Johnson being linked to a surf club in Galveston, and the two girls [missing from] Webster (Texas, in Harris County) being linked to a surf club in Galveston. It just astounded me that here we’ve got these links and leads weren’t really followed up.

There’s another newspaper article a day or two later, where the sheriff of Galveston County said that that theory is basically nuts. It’s just befuddling.

What kind of challenges were early investigators confronted with when digging into these disappearances and murders?

There’s a whole host of reasons. The initial investigating officer gets the call and he’s told that two females were last seen going to school that morning, or were last seen at a party. Back then, they would say ‘Wait 24 hours and call us back if they come back home.’ They take a missing-person report but there was no real sense of urgency to look for these missing girls.

The ’70s was a different era. The 15, 16-year-olds were hitchhiking. If remains were found, months and sometimes years had gone by before they were positively identified as the victim or the runaway. Then the case became a homicide case. But the lapse in time is a huge factor. You think these murders are isolated, but they’re not.

Homicide detectives were going out every night working other murder cases. There were thousands of murders a year in Harris County, probably many hundreds in Brazoria County and probably hundreds in Galveston County. So caseload was a big factor. Poor communication and the [lack of] sharing of information between agencies was a huge factor. Politics is also a huge factor in some of these investigations, which the show will show at some point.

Do you think that any of the cases may have been handled differently if these teenage girls were older, well-respected women in their community—or men?

So much information was lost. The suspect would abduct from one jurisdiction or from one city or from one county and the [victims’] bodies would be found sometimes years later—usually across the county line or across city limits.

You have an agency working a murder, but they don’t know whose body it is. There’s no communication. There were no databases like there are today. And sometimes you didn’t haven’t enough remains to do an immediate identification, and agencies [would have to] go back to the scenes and sift through the dirt and mud to find a couple teeth that would help them make a positive identification. Then you’ve got to find dental records.

Because of the lapse in time, you could have two years [or more] where there’s no [murder] investigation [yet]. [By the time the victim is identified] so many clues wash away or are long gone.

It seems like there are such strong feelings of guilt among the friends and family members who saw a victim last. ‘If only I wasn’t on the phone and picked her up…’ or ‘If only I had given her a ride….” Is this guilt a common thread in the murder cases you’ve investigated throughout your career?

Absolutely. In one instance in Galveston, a young girl wanted to spend the night at her best friend’s house. Her parents talk about it. Daddy doesn’t want it to happen. Mama says it’s going to be alright. The next day, the daughter’s missing.

Think about being a brother or sister and leaving your younger sibling behind while you ride off and see them thumbing a ride on the side of the road. Then they disappear. It’s gut-wrenching. You live it over and over again. You never forget. That’s what these family members are going through.

It must be emotional for anyone investigating unsolved murder cases. How do you separate your own feelings from the job?

It does get emotional. Investigators learn to turn on and off. It’s emotional when you see family members [of the victims] and when you’re giving them the news. It’s emotional when you’re getting that conviction in the courtroom. But there are always other cases for you to turn your attention to.

What was your immediate response after you read Ed Bell’s confession letter for the first time?

It was, ‘Damn. The man did it. He’s the guy.’ He actually names Debbie and Maria from Galveston. He gives details. I already knew the cases by then, and I’d seen the forensic reports. The [details] matched.

I’ve seen a lot of false confession letters and, in my opinion, this one is real.

What did you feel about the fact that such an important piece of evidence that could potentially solve these murders, was locked away and forgotten about for so long?

I didn’t have any negative feelings about that. I thought, ‘Why did that happen?’ But the one thing that really bothered me is [I learned] the letter was never shared with the parents of Debbie Ackerman or Maria Johnson.

Ed Bell is up for parole soon. What do you think is going to happen?

What I think and hope is going to happen is his parole is going to be denied. He’s never really shown any remorse for what he’s done—even [for] the [one] murder that he’s been convicted of. He should never get out of prison. I hope he rots in hell.

[Editor’s Update: Edward Bell died in prison on April 20, 2019.]

Related Features

Why Are There More Serial Killers in the U.S. Than Any Other Country?