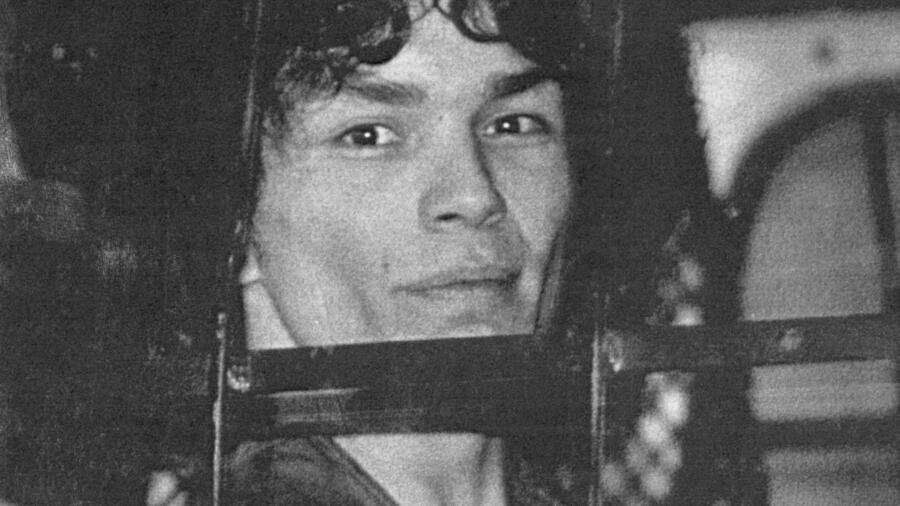

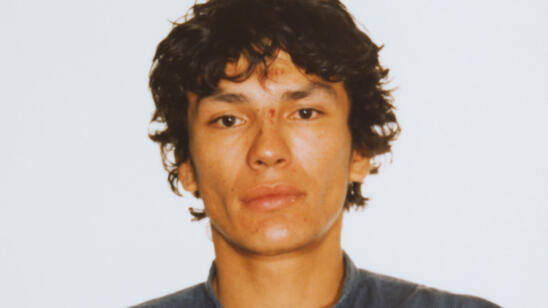

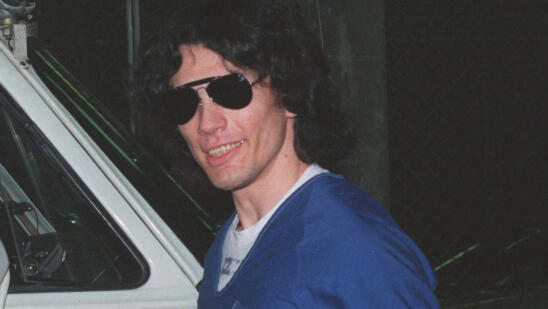

Beginning in 1984, Richard Ramirez, known as the “Night Stalker,” terrorized the Greater Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay areas of California. For more than a year, the now infamous serial killer creeped into homes, where he attacked, tortured and murdered his victims. He mutilated a number of those he killed and abducted and sexually assaulted others. Ramirez’s violence came to an end on August 31, 1985, when a crowd of citizens surrounded and captured him on the streets of East L.A.

“We have alleged these murders are in the first degree, were premeditated and occurred during burglaries and other crimes. We are asking for the death penalty in this case,” prosecutor Philip Halpin said in his opening statement at the start of Ramirez’s trial.

[Stream an episode of First Blood on Richard Ramirez and his victims on the A&E app.]

The jury agreed, and in 1989 convicted Ramirez of 13 counts of murder, five attempted murders, 11 sexual assaults and 14 burglaries. He was sentenced to die in California’s gas chamber. But the Night Stalker would die of natural causes, not an execution.

From Death Row to Prison Infirmary

After his sentencing, authorities transferred Ramirez to California’s San Quentin State Prison, which sits like a fortress along the bay north of the Golden Gate Bridge. The California Supreme Court denied Ramirez’s first round of appeals on August 7, 2006. A month later, in September 2006, they denied his request for a new hearing.

While continuing to appeal his conviction and awaiting execution, Ramirez was diagnosed with B-cell lymphoma, a form of blood cancer. He also suffered complications from chronic substance abuse and a chronic hepatitis C viral infection, likely from intravenous drug use.

“If he was lingering, Ramirez would have been brought from death row to the fourth floor of the prison hospital at San Quentin,” Marvin Mutch, a former wrongfully convicted prisoner at San Quentin and policy advocate at Humane Prison Hospice Project, tells A&E True Crime.

But Ramirez’s time in San Quentin’s infirmary was likely much different than if he had received medical care outside of prison.

Terminally Ill and Imprisoned

When incarcerated, prisoners tend to age more rapidly. Because of past poor health behaviors (like addiction) and the stress of being in prison, they often become prone to illness and chronic conditions. By 2030, according to estimates from a 2018 study, one in three prisoners will be over the age of 55, increasing the likely population of prisoners diagnosed with conditions such as cancer, heart disease and liver and kidney disease. Many of these illnesses will eventually become terminal.

Ramirez likely suffered from terminal cancer, although the full nature of his illness remains unclear.

Terminally ill prisoners, according to Mutch, have physicians and nurses who administer drugs and provide other medical necessities as needed. Unlike in the civilian world, they do not receive around-the-clock care. Some prisoners are granted compassionate release (early release based on extraordinary or compelling circumstances like a terminal medical condition). Others are entered into end-of-life programs.

In the U.S., about 3.5 percent of the nation’s prisons have on-site hospice programs. One is located at the California Medical Facility in Vacaville, just outside of San Francisco. San Quentin inmates can qualify for this program, but there are only 17 beds for eligible prisoners.

Most often, when prisoners at San Quentin—especially those on death row—take a turn for the worse, they are transported by ambulance to a local medical facility, according to Mutch.

Ramirez’s Last Days

Sometime in early June 2013, Ramirez, at age 53, was taken from San Quentin to Marin General Hospital in Greenbrae, California. On June 7, 2013, he took his last breath. He likely died alone, as friends and loved ones are not allowed inside secured rooms.

“You are shackled to your bed, and there’s a guard outside the room,” Mutch explains. “If hospital staff knows that death is imminent, there might be a nurse present. Unfortunately, most of the time, they find that the inmate has already passed when they do their checks.”

It’s unknown whether, at the end, Ramirez became remorseful or troubled by his crimes. But those familiar with his case believe he would not have been repentant.

“Ramirez was a cruel and unrepentant psychopath, so it is very unlikely that he ‘found Jesus’ before he died,” Scott Bonn, a criminologist and author of Why We Love Serial Killers, tells A&E True Crime.

[Stream Invisible Monsters: Serial Killers in America in the A&E app.]

Ramirez, a self-professed Satan worshipper, spent 23 years on death row. At the time of his death, he became the 59th California inmate to die of natural causes while awaiting execution.

By most estimates, Ramirez would have been in his 70s before being placed in the gas chamber due to California’s lengthy appeals process. Since he was not executed, Ramirez never had an opportunity to give the public a final statement or speak his last words. But at his sentencing he did address the court: “You don’t understand me. You are not expected to. You are not capable. I am beyond your experience. I am beyond good and evil. I will be avenged.”

Related Features:

Richard Ramirez and Other Serial Killers Whose Family Members Were Murdered

How Richard Ramirez’s Decaying, Gross Teeth Helped Catch and Convict the Serial Killer

Was a Bad Childhood to Blame for ‘Night Stalker’ Richard Ramirez Becoming a Serial Killer?