In “ShadowMan: An Elusive Psycho Killer and the Birth of FBI Profiling,” reporter Ron Franscell tells the story of how one case helped convince the FBI that there was merit to the process of “criminal profiling.” Today, profiling—and the hunt for an “unknown subject” or “UnSub”—is a tool relied on by the agency’s Behavioral Analysis Unit, formerly known as the Behavioral Science Unit (BSU).

Profiling is a way to reverse-engineer an investigation: Federal agents and specialists in human behavior will look at the clues from an unsolved case, then try to form a portrait of their anonymous culprit.

Part mystery and part history, “ShadowMan” recounts the first case in which the Bureau used a profile to successfully apprehend a suspect. The story begins in the summer of 1973 at a campground in Manhattan, Montana. As her siblings slept beside her, 7-year-old Susan Jaeger was snatched from a tent in the middle of the night.

Franscell spoke to A&E True Crime about the disappearance that spurred what was then the largest manhunt in Montana history, and the tenacity of a grieving mother fixated on proving that Vietnam vet David Meirhofer—who committed suicide within hours of his arrest—was the man responsible.

Can you describe the circumstances that brought the FBI to Manhattan, Montana that summer?

A family from Michigan was visiting a campground there. There were five children. Somebody cuts a hole in the tent and drags one of them out, without the others ever knowing. Susie Jaeger just disappears into the night. That causes the FBI to get involved, because of the “Little Lindbergh law” [which made kidnapping a federal crime].

Hundreds of tips roll in, but the FBI agents and local law enforcement have no leads, no real suspect, no evidence to speak of.

In February of the following year, Sandra Smallegan, a local 19-year-old, goes missing. There’s no idea in that moment that these cases might be related. So, they search for Sandra and ultimately find her car hidden in a barn at an abandoned ranch. That focuses the investigation [there], where they begin to find there are charred bones that have been pulverized and scattered around the property.

What did the bone samples reveal?

Experts in Montana and at the Smithsonian quickly came to the conclusion that these fragments belonged to two females: one very young, and the others to an older female. At that point, [the FBI] deduced that these were the remains of Susie Jaeger and Sandra Smallegan. But again, they have no suspects.

The lead investigator was Montana FBI agent Pete Dunbar. Dunbar went to Washington and finessed a ‘criminal profile’ out of a bureau that at the time considered that process, as you’ve said, ‘hokum.’ How did he do it?

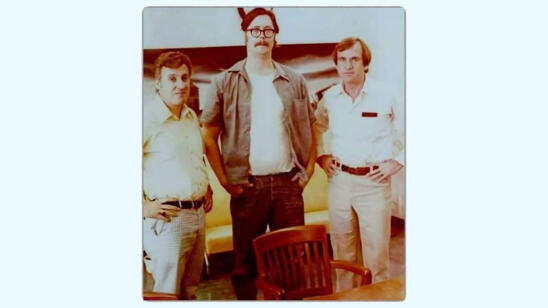

Dunbar has to go back to Quantico [Virginia] for the periodic training that FBI agents go through. While he’s there, he attends a workshop by two agents, Patrick Mullany and Howard Teten. Teten and Mullany have this idea that by looking at crime scene evidence, you could learn certain things about the ‘unknown subject’ and his behavior. They had no idea what to call it, so they just attached the words ‘criminal profiling’ to it.

Most law enforcement believed that you solved crimes by having boots-on-the-ground, talking to people and deducing what had happened. J. Edgar Hoover himself believed that. But, when Dunbar meets Teten and Mullany, Hoover has recently died and there’s a bit more progressive management coming in at the FBI. Clarence Kelly [Hoover’s successor] gave Teten and Mullany a tentative green light to go forward.

Law enforcement had dabbled in profiling before the Montana case, sometimes with erratic results. But this was the first time the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit created a full profile intending to identify a serial killer. What did Mullany and Teten tell Dunbar about his Montana UnSub?

With the information from Pete Dunbar, they started by asking: ‘What do we know about the place?’ It’s a small, rural area. So, they believe that the guy who did this is from there, for the reason that he was bold: He cut a hole in a tent. He drags out a little girl. Now he’s got to carry a girl, who’s possibly struggling, back to a vehicle, which is at least 100 yards away…so he’s probably not unfit. He could move around at night, knowing where he’s going.

The stealth and the risk involved in both kidnappings suggested military training. The fact that most of the young men from Gallatin County [Montana] had enlisted or were drafted for Vietnam made that a likelihood.

On the first anniversary of Susie’s disappearance, Meirhofer called Marietta Jaeger, Susie’s mom—anonymously—using skills he learned as a communications specialist in the military. Marietta kept him talking for an hour, on a line monitored by the FBI. What could that have been like for a grieving mother?

Marietta is as much a hero in this story as Pete Dunbar or the profilers themselves. The bravery she showed was amazing. I think it begins with that first phone call, as she deals with him in a forthright way. That throws him off.

Before his arrest, Meirhofer and Marietta met face-to-face. His lawyer allowed it, because David had breezed through polygraph tests. He was confident in David’s innocence.

Even to this day, when you talk to Marietta [who now lives in a Florida senior community], you get some sense of that strength she showed in the confrontation with him in the lawyer’s office, where she is looking him in the eye and saying: ‘I know you did it.’ And he’s denying it. But he’s no longer in control. The only person who ever throws him off track is Marietta.

After all this, Marietta would spend the bulk of her adult life advocating against the death penalty, on a national scale. What went through your mind, speaking to her?

Marietta underwent this transformation from being a grieving, frightened mother involved with this horror and became a woman who forgives this monster and would have argued against his execution. Her feeling is: ‘I would prefer to save the lives of these people, because I believe that’s what Susie would’ve wanted.’ I was fascinated by that.

Related Features:

Ann Wolbert Burgess on Learning from Serial Killers While Working With ‘Mindhunters’

FBI Profiler John Douglas on the Racist Rampage of Joseph Paul Franklin

James E. Amos, the Early FBI’s Longest-Serving Black Agent, Worked on High-Profile Cases