Her case captivated the country. Now she’s cashing in.

Angelika Graswald, aka the “Kayak Killer,” was convicted in 2017 of criminally negligent homicide for the 2015 death-on-the-Hudson of her fiancé, Vincent Viafore, after confessing to pulling the plug from his kayak and tampering with his paddle. According to the prosecution, Graswald was motivated, in part, by the prospect of collecting on Viafore’s life insurance. She served just under two and a half years before being released in December 2017. (Time spent in jail awaiting trial went toward her time served.)

If the prosecution’s assertion is true and life insurance was her motivation, she won out. In August of last year, she reached an out-of-court settlement with Viafore’s family to receive some of the insurance money. While the amount of her settlement went undisclosed, Graswald had originally been listed as a 45 percent beneficiary on his death benefit—which adds up to just over $491,000.

[Watch Invisible Monsters: Serial Killers in America in the A&E app.]

Originally, Viafore’s mother Mary Ann Viafore had stated that the family planned to fight the insurance claim via a wrongful-death lawsuit.

Graswald’s attorney Anthony Piscionere said Graswald was entitled to the insurance because his client hadn’t acted maliciously.

“A person in New York cannot benefit from someone’s death if they’ve intentionally or recklessly caused their death,” Piscionere tells A&E True Crime. “The Viafore family would’ve had to still tried to prove that she intentionally or recklessly caused his death…and I don’t think the evidence was there.”

The attorney representing the Viafore family didn’t respond to request for comment.

A&E True Crime looks at some other infamous criminals who profited in some way from their misdeeds, showing that sometimes crime does indeed pay.

Henry Hill

A mafioso and career criminal directly involved with the infamous Lufthansa Heist, Henry Hill became an FBI informant, admitting to a litany of crimes committed during more than 20 years working with the Lucchese crime family. Among his many misdeeds, Hill says he helped bury the bodies of more than a dozen murder victims.

But after going into a government witness-protection program, Hill cashed in on his knowledge. He was paid more than $550,000 over the years for his story, giving an extensive interview with author Nicholas Pileggi for a book about his life in crime, “Wiseguy,” which later became the basis for Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas. During the film’s production, Hill served as a consultant to Robert De Niro.

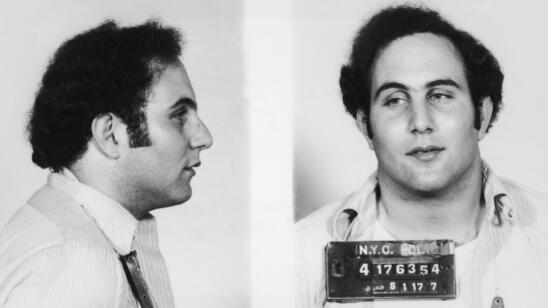

The money didn’t come easily, though. In 1991, the New York State Crime Victims Board ruled that Hill’s money should instead go to the board for redistribution to victims of the Lucchese crime family, citing the state’s “Son of Sam” law, which makes it illegal for criminals to profit on their stories. (The 1977 law was named after serial killer David Berkowitz, nicknamed “The Son of Sam,” who sold the exclusive rights to his story.)

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Hill’s favor, calling the state government’s money grab an infringement on the First Amendment. But rather than bring an end to New York’s Son of Sam laws, that ruling only pushed the state to expand the law further, says Leon Friedman, a professor of civil liberties at Hofstra University and an attorney who counseled famed “diet-doctor killer” Jean Harris on a similar Son of Sam case.

When the Supreme Court ruled that “you can’t focus on only First Amendment-generated funds,” the state solved the issue of discriminatory fund freezing by ruling that all earnings of convicted felons are susceptible to victim payouts. After the Supreme Court ruling, he adds, “it doesn’t matter where you get the money. Lottery, aunt gives it to you, you invented something new…if you hurt somebody 50 years ago, 50 years later they can still sue.”

John Wayne Gacy

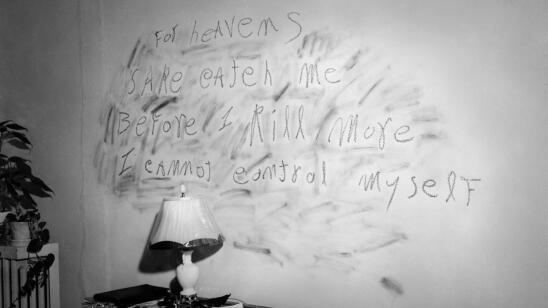

Nicknamed the “Killer Clown,” John Wayne Gacy’s criminal career was the stuff of nightmares. A sadistic sexual killer who dressed as a clown and performed at children’s parties, Gacy would abduct and murder teenage boys as young as 14 years old, torturing them for days before ending their lives and burying their bodies in the crawl space of his home.

After he was arrested, he was convicted of 33 murders and sentenced to death. And that’s when the painting began.

Gacy was prolific. His clown persona (named “Pogo” or “Patches”) would feature prominently in the artwork, and by the time of his execution in 1994 he had created more than 2,500 original paintings. The Illinois State Attorney General was never able to determine how much money Gacy made from those works of art, but today individual Gacy paintings can sell for upwards of $175,000, part of a disturbing new art trend: murderabilia, the artwork of serial killers.

Not all art dealers are comfortable capitalizing on a killer’s creativity. Shortly after Gacy’s execution, a dealer bought 21 of the works and burned them in a bonfire so as to “get them off the face of the earth.”

Charles Manson

Like Gacy, Charles Manson’s brutality captivated the nation and turned him into a public figure with an image to sell. But a lot of the capital Manson earned wasn’t from artwork. It came from his his brand.

In the early 1990s—more than 20 years after Manson had been put behind bars for his role as the cult leader and mastermind behind the murder of actress Sharon Tate and six others—Zooport Riot Gear reached a royalty agreement with Manson and began printing T-shirts with Manson’s likeness. The shirts sold for $17 apiece, of which the apparel company paid the killer 10 cents.

It’s unclear how much money Manson made off those shirts…or the myriad of murderabilia he produced in prison. But Friedman says the fact that the shirts didn’t directly mention the brutal crimes has no bearing on his rights to profit.

“It applies to any money that he gets from any source,” Friedman says. “Any victim can claim it.”

That would’ve been true—for a time.

In 2002, California’s Supreme Court ruled that victims could only claim funds earned within 10 years of a conviction. For Manson, that meant from the moment California’s new Son of Sam laws were enacted until his death in 2017, he was free to earn all he wanted.

After Manson passed, there was a contentious battle over his property—despite the killer having been incarcerated for the last five decades of his life. At the time, Manson’s self-proclaimed “son” Matthew Roberts (a.k.a. Matt Lentz)—one of four people fighting over Manson’s estate—claimed the cult leader was worth millions, including the value of artwork and music rights, among other things. As of the publication of this article, the legal battle is ongoing.

More Features:

Casey Anthony’s Life Now, 10 Years After Daughter Caylee Vanished

Lufthansa Heist Murders: How Paranoia and Greed Led to the Deaths of 6 Mobsters and Associates