Timothy McVeigh killed so many people that there wasn’t enough space at the federal penitentiary for all the victims’ family members who wanted to watch him die—so they watched, together, via a remote closed-circuit television instead.

McVeigh’s 1995 bombing of a federal building in Oklahoma City killed 168 people in all, including 19 children who were attending daycare in the complex. It was, at the time, a terrorist attack of unprecedented magnitude on American soil.

His subsequent execution left an indelible mark on those who attended it.

“[The attack on] Oklahoma City was bloody and loud and smelly and urban,” says Crocker Stephenson, a retired reporter for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel who both covered the bombing for several weeks and was one of 10 journalists who witnessed McVeigh’s execution. “The execution chamber was quiet, and brightly illuminated, and clear. It was like the opposite of what happened in Oklahoma City. Oklahoma City was horrifically savage. And the execution chamber was so formal.”

A&E True Crime looks at the last days of Timothy McVeigh’s life.

McVeigh’s Letters to the Press

In the months before McVeigh’s death, he wrote several letters to The Buffalo News¸ his hometown newspaper. Although he expressed hints of remorse for the lives he took, the apology was conditional.

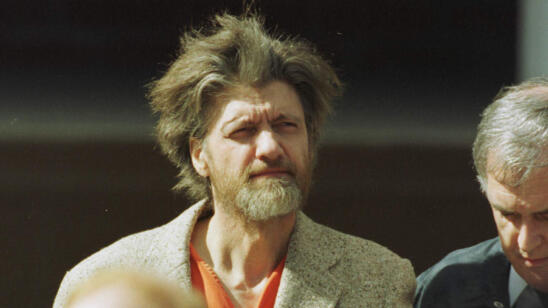

[Stream Waco: Madman or Messiah in the A&E app.]

“I am sorry those people had to lose their lives,” he wrote to the newspaper. “But that’s the nature of the beast.”

In those letters, he described himself as a soldier at war with the federal government, with the bombings a “legit tactic,” although he added that, in retrospect, he wished to have put his marksmanship to use and instead focused on police and governmental assassinations.

“He would write letters all the time, proclamations that just reinjured so many people,” says Stephenson, who is personally against the death penalty, but adds: “I couldn’t imagine a person that deserved to be executed more than Timothy McVeigh.”

The Final Day

McVeigh was moved from his holding facility at the U.S. Penitentiary in Terre Haute, Indiana to the execution chamber in the early morning hours of June 10, 2001—the day before his execution. While there, when the water of the shower initially ran cold, he joked with guards that it was “cruel and unusual punishment.”

He was administered Catholic last rites—a surprise to his attorney Nathan Chambers, given McVeigh’s professed agnosticism.

For his last meal, McVeigh ate two pints of mint chocolate chip ice cream. In the evening he watched television until 9 p.m., according to the prison log, and then turned off the television for sleep but was restless, tossing and turning throughout the night. At 3:00 a.m. the day of his execution, he watched more television. His attorneys visited him at 4:30 in the morning, and left 20 minutes later. The execution was slated for 7:00 a.m.

The Execution Itself

Kevin Johnson, a reporter for USA Today who covered the execution, remembers how physically close McVeigh was to the reporters.

“We were directly at his feet,” Johnson says. “He was stone faced, but he made an attempt to look into each of the rooms—at the attorneys who were gathered in a room to his left, at us reporters and then at the room of survivors’ families who’d gathered in a room to his right.”

The survivor room was sealed off with one-way glass. A mounted camera beamed the execution back to 232 victims’ relatives in Oklahoma City.

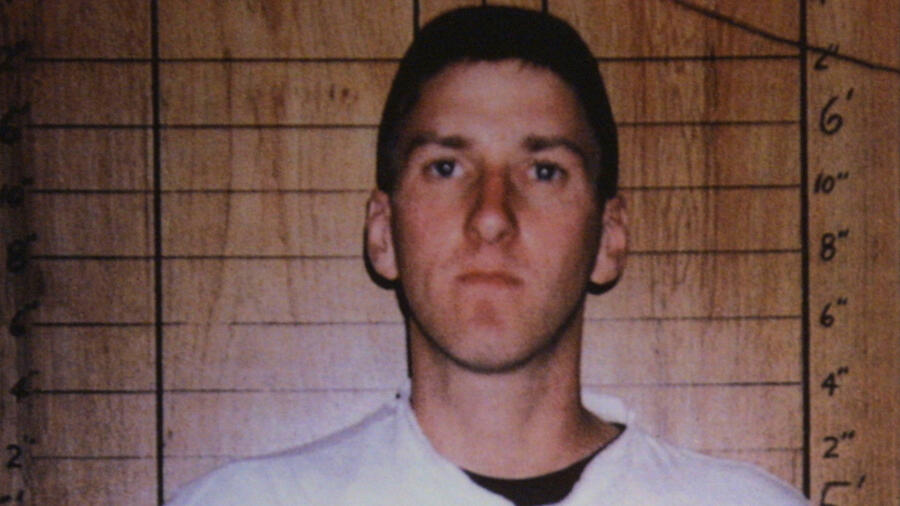

Johnson, who had interviewed McVeigh years before while he was still awaiting trial, says McVeigh looked different on the day of his death.

“During the trial, and even prior to that, he was very animated—cocky almost… By the time he got to the gurney…he looked like the life had pretty much run out of him… He had lost weight. His pallor was chalky. His eyes were a bit hollow.”

Stephenson adds, “There was a white sheet laid over him, and it was particularly white. His skin seemed papery. His head had been shaved, but it had grown in over the day.”

McVeigh spoke no last words, and didn’t respond to the opportunity to speak, but had a handwritten transcription of the 19th-century poem “Invictus” by British poet William Ernest Henley distributed to those in attendance, which opens with the stanza:

Out of the night that covers me

Black as the pit from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

The execution itself was fast. Through an intravenous needle inserted into his right leg, McVeigh received a three-drug injection: sodium thiopental (which would render him unconscious), pancuronium bromide (which paralyzes voluntary muscles) and potassium chloride (which quickly induces cardiac arrest and ultimately causes death).

McVeigh was pronounced dead at 7:14 a.m. on June 11, 2001, within four minutes of the first drug’s administration. His eyes remained opened the entire time.

After McVeigh’s Death

McVeigh expressed a desire to have his ashes scattered, although the stated preferred location would change. Sometimes he said he wanted them scattered over the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas—a nod to the violent siege by federal agents on the religious compound, which left 76 people dead and which served as one of the motives behind the Oklahoma City bombing. He also considered having his ashes scattered at the Oklahoma City bombing memorial, but ultimately decided that would be “too vengeful… it’s not me.”

Ultimately, the final spot remains undisclosed.

Related Features:

David Copeland: Where Is the London Nail Bomber Now?

A Retired Bomb Technician Explains Package Bombs and Trip Wires Used in Austin Bombings

Bomb Squad Commander on ‘Pizza Bomber’ Scene Reveals Changes Made in Aftermath