In the late 1960s, Liza Rodman spent summers hanging out with Tony Costa, the handyman at the Royal Coachman, the Provincetown, Massachusetts hotel where her mother, an alcoholic who loved going out to bars, worked. One of the many people Rodman’s mom enlisted to watch the 8-year-old and her sister, Tony was fun, funny and charming.

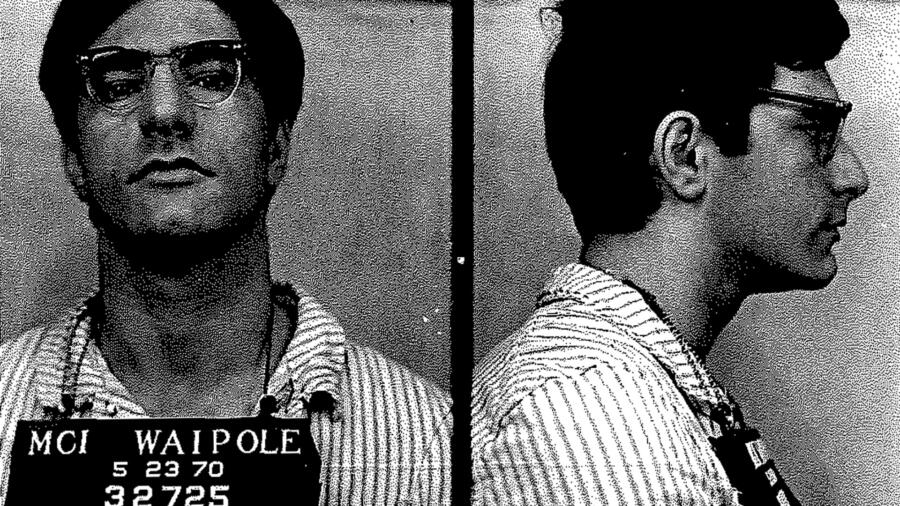

He was also a serial killer. Costa was convicted of murdering two women, Mary Ann Wysocki and Patricia Walsh in May 1970, and burying their bodies in the woods of Truro, near Provincetown. According to investigators and his defense team, he was also suspected of murdering at least three other women.

More than 30 years later, Rodman found herself having nightmares where an “anonymous man” was coming for her. One night in 2005, the nightmare ended with the anonymous man revealing himself as Tony.

Throughout her life, Rodman’s relationship with her mother was strained. Still, she needed to know more about her early years. Soon after her dream about Tony, Rodman invited her mother over for dinner and asked, “Did something happen to me back then that you’re not telling me?” She said, of Tony, “He was always so nice to me. What do you remember about him?”

Rodman’s mom replied, “I remember he turned out to be a serial killer.”

A&E True Crime spoke with Rodman about her book, The Babysitter: My Summers with a Serial Killer, co-authored by Jennifer Jordan, and the years that followed this shocking revelation.

What was it like for you, when your mom said the words, ‘serial killer’?

I still have the most vivid memory of it. I was cooking, and I had people in the house for dinner. I was talking to my mother, and actually my aunt was there as well. They said it as if it was nothing. As if, ‘It was 50 years ago, and what’s the big deal?’ But it wasn’t that way for me. It was a slow-motion moment.

I thought, Oh my God. I’m going to find out more about this. I was learning about something I already knew, but I knew it on a very different level.

What kinds of hints did you later realize were pointing to the truth, before you knew for sure?

I had nightmares, and they were recurrent. There was always this man with no face, and he was always coming after me.

Sometimes he had on a white bathrobe; sometimes he was holding a rifle. Sometimes he was in the Royal Coachman lobby. Sometimes he was in my grandparents’ funeral home. Sometimes he was in a house that wasn’t built yet. As I was researching I was having these dreams, but I did not make the connection between them.

I knew it was him in the last dream I had. I saw his face and I was like, holy sh*t. What does this mean? And that’s why I asked [my mom].

How do you compare your childhood perception of Tony to what you now know to be the truth?

He really was a sociopath and he turned up that charm. Those are the moments that I remember now. At the time I thought, This is great. I’m drinking soda, I’ve got my cookie. It was fun [being with him].

The whole point of the book was that you [can] compare and contrast the care of your mother or the care of your other babysitter with the care of Tony. And, for me, the serial killer was the nicest guy on the block.

Tony would take you and your sister into the woods in Truro, a short drive from Provincetown to hang out. You later learned some of his victims were buried in that vicinity. How do you remember it?

For me, [being in the woods] was a happy [time], and that’s what I had to come to terms with: I was happy standing on top of those leaves.

I know Tony didn’t like to go out there, even though he said he loved it. He was afraid to go out there alone. We read some police interviews, later, from some young women—much older than I was, but young women—who told the story about Tony telling them he was afraid to go out there alone, so he would bring people with him.

How did you deal with all of this as you learned more about Tony?

I had to be OK with it. I had to be OK with the autopsy photos [of his victims] on one side, and my memories of Tony on the other. I had to find a way to reconcile that. And that’s what this book is.

Do any moments come to mind, where you remember your experience as a kid, but now know there was a lot more going on?

Yes. I remember when my mother was signing us up to go to grades two and four, in the basement at Provincetown High School, because the new school was being built. Susan Perry’s friends were signing up [at the high school], and then they were going to the apartment in Dedham, Massachusetts where [I now know] Tony was about to kill [Susan].

How do you feel about Tony now?

I know what Tony did, and for that my heart breaks. It’s why we dedicated the book to the women [he killed]. At the same time, [Child Liza], who had a really f*cked-up family life, and who I often refer to in the third person now, was treated well by him, and by his mother. They were warm and wonderful [to me]. You don’t forget that when you don’t have it at home.

What are your thoughts about Tony from a mental health standpoint?

He had to have been afraid of his own mind. I know he was studying his own mind. There was so much opportunity for people, had they known what they were dealing with, or even if he’d known what he was dealing with, to stop what happened.

Tony was not addicted to his substances, even though he did a ton of drugs. In his case, his addiction was necrophilia, I guess, and mutilation.

I hope that’s part of the conversation as we go forward: Pay attention, because by bringing us or anyone else out to those woods—the same woods he used as his burial ground—this guy was calling out for help.

Related Features:

Connecticut Serial Killer William Devin Howell Describes the Shocking Details of His Crimes

What It’s Like to Grow Up With a Serial-Killer Dad: ‘Happy Face Killer’s’ Daughter Reveals Grief