The U.S. originally started the federal witness protection program to protect people from the mob. And the people who received protection? They were usually part of the mob too.

During the 1960s, Mafia family members routinely murdered federal witnesses who testified against them, making potential witnesses too scared to come forward. Gerald Shur, an attorney for the U.S. Department of Justice, thought there should be a way to help protect those witnesses. His solution: to establish the U.S. Marshals Service Witness Security Program, also known as WITSEC. Since 1971, it’s provided more than 8,600 witnesses and 9,900 of their family members with new identities.

Most of the witnesses who’ve entered the program are members of mobs, gangs, cartels or terrorist rings who testify against their fellow members in return for reduced sentences or dropped charges. Some have been pretty high-profile. Henry Hill, a member of New York City’s Lucchese crime family portrayed in the 1990 movie Goodfellas, spent two years in the witness protection program with his wife and children before blowing his cover.

Witnesses and their families are free to leave the program whenever they like. If their security is compromised, U.S. marshals can relocate them again, and those who break the rules too many times may lose federal protection. However, investigative reporting has revealed that there is little long-term oversight in the program, and many witnesses have continued to associate with people from their old life and make money through illegal activities after joining WITSEC.

The Rules of WITSEC

A witness can enter the protection program alone or with family, but this is usually limited to their nuclear family. Witnesses and their relocated family members have to agree to cut off almost all contact with their extended family to protect their new identities. From that point on, they’re only supposed to communicate with extended family through secure Marshal Service channels; and even then, they’re not supposed to reveal any details about their new life that could blow their cover.

Marshals help people in the program come up with new last names (and sometimes new first names), as well as new backstories for when others ask them about their lives. For young children, maintaining these backstories can prove especially difficult. Marshals provide these families with new Social Security numbers and birth certificates, and they help the parents find new homes and new jobs.

The only requirement witnesses need to enter the program is for prosecutors or law enforcement to feel there is a credible threat against their life. It’s not supposed to depend on how much information witnesses can provide or how crucial they are to a particular case.

“The people whom I sponsored were informants, cooperators and witnesses against the Colombian Cali Cartel…and I never had any candidate rejected,” Ephraim Savitt, a New York City defense attorney who worked as a federal prosecutor during the 1980s, tells A&E True Crime. “I also sponsored one informant against the mafia. And frankly, that informant didn’t give us, as prosecutors, that much of a yield; but he was facing danger.”

The Reality of Being in the Witness Protection Program

It’s difficult to know what happens to witnesses who stay in the program because, well, they’re not supposed to tell anyone.

In 1996, the U.S. Marshal Service allowed The New York Times to conduct an interview with a protected witness family at a “neutral site,” but they couldn’t reveal identifying details about their new lives. Most of the time, if you read or hear a news story about someone in the witness protection program, it’s because they’ve already blown their cover.

This was the case with Wahed Moharam, the subject of a 2003 article in the Kansas City Star. Moharam left his daughter and first wife in New Jersey to enter the witness protection program because of testimony he provided for the 1993 World Trade Center bombing trial. U.S. marshals first placed him in Phoenix, then relocated him to Seattle after he allegedly broke a witness security rule that blew his cover. In Seattle, his cover became compromised again, and marshals relocated him to Kansas City, Missouri. There, he married a second time and allegedly blew his cover to his new wife. This time, the Marshal Service released him from WITSEC.

Moharam continued to live in Kansas City and may have stayed under the radar had he not begun to show up at Chiefs football games dressed as a Native American caricature and calling himself “Helmet Man.” This earned him some local notoriety, but after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, his second wife publicly revealed he’d been in the witness protection program. (She did this because of her unfounded belief that he was involved in the attacks.) The Chiefs asked him to stop coming to their games as Helmet Man out of concern that he was still in danger and someone could target him during the games.

Moharam’s story is unique, but Bill Moushey, a professor of journalism at Point Park University in Pittsburgh, suspects there are many more people in the witness protection program who break the rules without the U.S. marshals finding out. Moushey was a 1997 Pulitzer finalist for his reporting in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette about problems and risks within the witness protection program. He has interviewed dozens of protected witnesses, many of whom continued to associate with people from their old life or make money through illegal activities even after joining the program.

“Unless somebody gets arrested or has some kind of involvement with the law in some public way, [marshals] normally try to just not pay attention to [it],” he tells A&E True Crime.

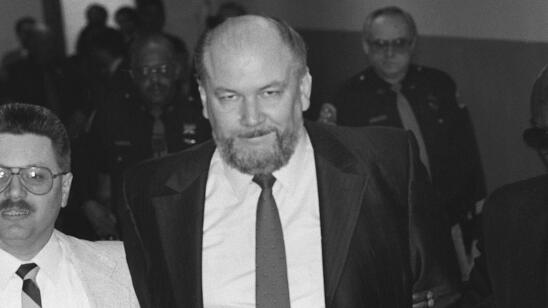

After Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano of the Gambino crime family testified against John Gotti, WITSEC relocated him to Phoenix. But Moushey says his location became common knowledge, and he soon started trafficking ecstasy with a white supremacist gang.

Authorities eventually prosecuted Gravano and sent him back to prison (he’s since been released), but less prominent witnesses who break the rules may go unnoticed. Moushey says most of the protected witnesses he’s talked to are unhappy with their new jobs, and this can make it easier for them to go back to illegal ways of making money.

For some, fear is a constant companion. Emad Salem, his wife and two children went into federal witness protection in the mid-1990s after he served as an undercover FBI asset who helped thwart terrorists planning an ambitious, multi-site attack in New York City.

Once in protection, Salem tells A&E True Crime, he lived in stress, exhaustion and fear, always looking over his shoulder, checking the rearview mirror and making unexpected turns to thwart anyone who may be following them. Salem says he amped up their home security with firearms, cameras and infrared sensors; he made sure his bed always faced the doorway. He excelled in martial arts and sometimes wore disguises when out in public.

In one stretch, the family had to move at least seven times in eight years, says Salem—once when one of the kids accidentally broke cover and once when a van tried to mow him down outside his place of work. Each time, they’d be forced to pack up their lives in hours, flown via private jet to a safe house in an undisclosed location and kept under lock and camera surveillance until their old identities were scrubbed and new ones created.

In each locale, Salem says, he started a new career to minimize the chance of being recognized. His jobs ranged widely, including tree trimmer, hotel manager, jewelry salesman, massage therapist, roofer and scuba diving instructor. In the meantime, he continued to do occasional work for the FBI, conducting training sessions for agents on how to work undercover with terrorists. He has since come out of the program.

Related Features:

Lufthansa Heist Murders: How Paranoia and Greed Led to the Deaths of 6 Mobsters and Associates

John Gotti: Why Did the Working Class Love the Mobster So Much?

‘The Iceman’: An Undercover Agent Reflects on Taking Down Notorious Hitman Richard Kuklinski