After 6-year-old William DaShawn Hamilton was killed more than two decades ago, his little body was left in a wooded area near a church cemetery in DeKalb County, Georgia.

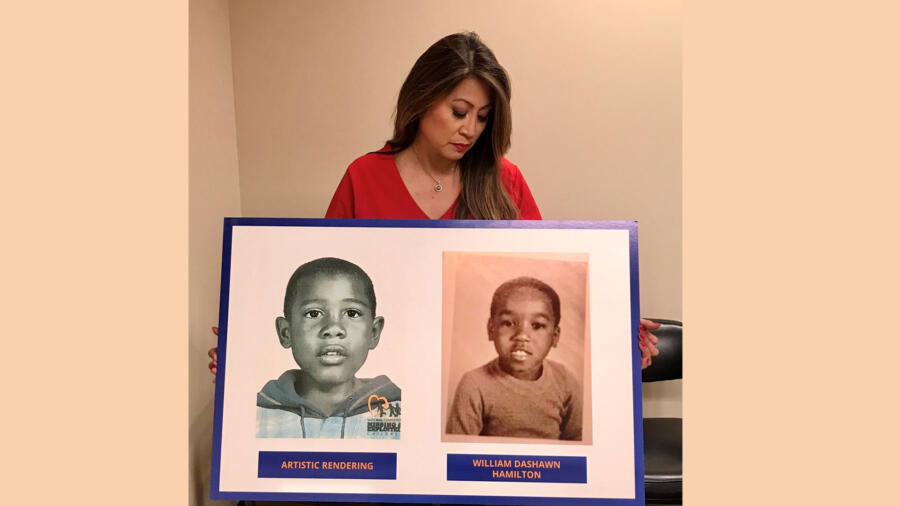

His remains were badly decomposed when he was found on February 26, 1999. Authorities didn’t know who he was, but they were able to determine he was African American, between ages 5 and 7 and had been dead for three to six months. He’d been wearing a blue-and-white plaid shirt, red denim jeans and brown Timberland boots. (The brand-name boots were a detail publicized in the attempts to identify him over the years.)

Despite investigators’ efforts, it took 23 years to finally solve the cold case. Authorities publicly disclosed William’s name in July 2022, when they also announced that his mother, Teresa Ann Bailey Black, was charged with his murder.

Solving the riddle of William’s identity happened in large part due to the perseverance of two women who, for different reasons, never forgot the child.

One was Ava, a friend of William’s mother who had forged an indelible connection with the little boy. [Editor’s note: Ava asked that her last name not be used publicly].

The other was reporter Angeline Hartmann, who repeatedly covered the case over the years, hoping someone would come forward to identify him.

[Stream episodes of Cold Case Files in the A&E App.]

That finally happened in May 2020, when Ava, a resident of Charlotte, North Carolina, placed a call to the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC), where Hartmann works, saying she believed the remains found in Georgia belonged to William. Her tip led investigators to solve the case.

A Loving Friend Who Never Forgot William

Ava tells A&E True Crime she spent a lot of time with William while he and his mother lived about three streets away from her home in Charlotte.

For nearly four years, she babysat him daily, before and after school, and the two became very close, she says. She remembers him as happy, smart and wise beyond his years, a boy who loved to read encyclopedias and was proud to know “big words.”

“He was a gregarious little fellow,” Ava says. “He was like an old man in a little boy’s body.”

His mother was her friend, but she was distant and impatient with William, Ava says. “She wasn’t a loving mom, or affectionate.”

Sometime in December 1998, Black withdrew William from school in Charlotte, authorities said. Black told Ava that she and her son were moving to Atlanta, Georgia, to be with relatives. Ava vividly remembers saying goodbye to William.

“We said each other’s name. William hugged me and I hugged him. We kept hugging,” Ava says. “She had to practically pry us apart to get him back in the car. That was it. That’s the last time I saw him.”

Black returned to Charlotte later in 1999, but William wasn’t with her. In response to Ava’s increasingly frantic questions, Black gave a variety of explanations for her son’s absence, Ava says.

“I was constantly approaching her, questioning her, asking her,” Ava says. “It was like, ‘How can you walk around here, living a life like William never existed?'”

Not getting any answers, Ava began searching for William. She looked up Georgia phone numbers in phone books at her local public library and made copies to take home. She called hospitals, police, homeless shelters, social service agencies and bus stations. She did that every day, sometimes for hours, at times even falling asleep surrounded by papers, she says.

Eventually, Ava lost track of Black. Life ticked by. She had a 20-year relationship and raised two daughters. And yet, she never stopped looking for William. She continued to scour websites and make calls, and her daughters grew up as if they, too, knew the little boy their mother had loved so much, she says.

Then one day in May 2020, Ava found a facial reconstruction rendering done by NCMEC of a little boy found in 1999 in Georgia.

“I screamed. My daughter came down running, and tears started running down my face,” Ava recalls. “I was sure. I felt, ‘This is him.’ And it was him.”

A Reporter Who Couldn’t Let It Go

Meanwhile, Angeline Hartmann, the first reporter on the scene when William’s remains were found, had never stopped doing her best to keep the case in the media spotlight.

Hartmann was a crime reporter at WAGA-TV in Atlanta, where she covered the case extensively over six years. She left in 2005 for a job with the TV show America’s Most Wanted, where she also covered the case. She then joined NCMEC as its communications director, and continued to make sure William would not be forgotten.

“With each career move, it just stayed with me,” Hartmann tells A&E True Crime. “I was there from day one, and kept doing story after story after story. I would talk about it in normal life, too—at a dinner party, or at a board meeting. Everyone who knew me knew about it.”

Experts created several facial reconstruction renderings of William over time. The unveiling of the first one in 1999 was especially poignant, Hartmann recalls. Authorities placed the rendering on a mannequin outfitted with clothes similar to those found with William’s remains, including child-sized boots that she could so easily imagine holding tiny feet, Hartmann says.”I thought, ‘How could you have a child in this neighborhood and nobody is collecting him? Nobody knows who it is and nobody is going to do anything about it? We have to keep doing all we can,'” she says. “I just knew I couldn’t let it go.”

Over the years, investigators followed multiple dead-end tips that led as far as Florida. An especially promising tip came from a teacher in Georgia, who thought the remains might have belonged to a student who’d abruptly disappeared from school, Hartmann says. “That one got people excited, but the cops found the boy,” she says. “There were a couple like that.”

NCMEC also was involved in the effort to identify William, featuring the case on its website and following leads. In February 2019, on the 20th anniversary of the discovery of the boy’s remains, a NCMEC forensic artist created a new facial reconstruction rendering. At the same time, Hartmann covered the case, again, in a new six-episode series on her own podcast, “Inside Crime with Angeline Hartmann.”

The following year, during one of her umpteenth searches, Ava stumbled across Hartmann’s podcast, which led to her to the 2019 NCMEC rendering in which she recognized William, the two women say.

Several Agencies Worked on the Case

Black was indicted in June 2022 in DeKalb County Superior Court with two counts of felony murder, two counts of cruelty to children, one count of aggravated assault and one count of concealing the death of another.

Black’s indictment states she administered a substance, or substances, containing diphenhydramine and acetaminophen (the combination is typically used to treat insomnia) to William; struck him in the head causing him serious bodily injury; and failed to seek medical treatment for him.

She was arrested in Phoenix, Arizona, and extradited to Georgia. She entered a preliminary plea of not guilty at her arraignment; as of December 2022, she was being held in Georgia’s DeKalb County jail, waiting for her case to be placed on the court’s pretrial calendar, DeKalb County Deputy Chief Assistant District Attorney Shannon Hodder tells A&E True Crime.

The investigation into William’s death was difficult from the beginning because his body was found after being exposed for months to the ravages of nature, says Lance Cross, director of the major crimes division for the DeKalb County District Attorney’s office.

“Evidence gets washed away, witnesses that may have been around have moved,” Cross tells A&E True Crime. “And anytime you have a victim found in an area they were not from, it makes it harder.”

The case initially was investigated by the DeKalb County Police Department and the DeKalb County Medical Examiner’s office. The DeKalb County District Attorney’s office got involved in the case after Ava called NCMEC, with investigators traveling to North Carolina and Arizona as part of their probe, Cross says. DNA collected from Black in early 2022 led to the boy’s identification, authorities said.

Prosecuting a murder more than two decades later is a rare occurrence, and it’s even more significant when the victim is an innocent child, Hodder says.

Hodder says she can’t forget the moment an anthropologist carefully took William’s bones out of a plastic bag and laid them on a table. The bones were so small, they could have fit into a shoebox, she says.

“It sort of haunts you, to know who he is,” she says. “To be able to put a name to him and to find the person responsible, to indict them and try to get justice for [the victim]…it’s something you always hope for.”

Hodder and Cross say they were amazed at Ava’s commitment to never give up on finding William. Both also credited NCMEC with vetting tips and setting the stage for the resolution of the case.

“When you have a victim like William, it’s inspiring,” Hodder says. “It moves people to work together.”

Finding a Measure of Peace

Ava and Hartmann have become friends since meeting in July 2022, and plan to attend Black’s murder trial.

After 23 years of searching for William, Ava says she feels conflicting emotions.

“It’s a joy, because I know he lives at peace now that he’s been found,” she says. “But it’s always a sadness, because seeing him as a child, seeing how happy and intelligent and smart he was… So many possibilities of what he could have done or who he could have been.”

She hopes to get permission to have William’s remains cremated and keep his ashes in her home, she says.

Hartmann says she is moved each time she looks at William’s only known photo. “It’s heartbreaking, but it’s also beautiful at the same time,” she explains. “I cannot speak enough about how strongly I feel about Ava and what she did, and how she just never gave up.”

Ava says she feels similarly about Hartmann’s commitment to covering William’s case. “We were on parallel paths and we didn’t know it,” she says.

The Dekalb County District Attorney’s Office continues to seek information from anyone who knew William DaShawn Hamilton or his mother, Teresa Ann Bailey Black. Anyone with information is asked to call the DeKalb District Attorney’s office cold case tip line at (404) 371-2444.

Related Features

The Murder of Megan Kanka: Why Megan’s Law Was Created

Angeline Hartmann on Jayme Closs and Misconceptions About Missing Children Cases