Warning: The following contains disturbing descriptions of violence, including sexual violence. Reader discretion is advised.

Most people who visit Yosemite National Park are overwhelmed by its serenity. Any danger (it seems) comes on four legs: mountain lions, black bears.

But for six months in 1999, brutality at Yosemite had a human face. Four female victims, two teens and two adults, were found dead in the vicinity of the park. Some were stuffed into the trunks of rental cars, their bodies burnt. Another was decapitated. All were killed at close range—strangled to death or slashed across the throat.

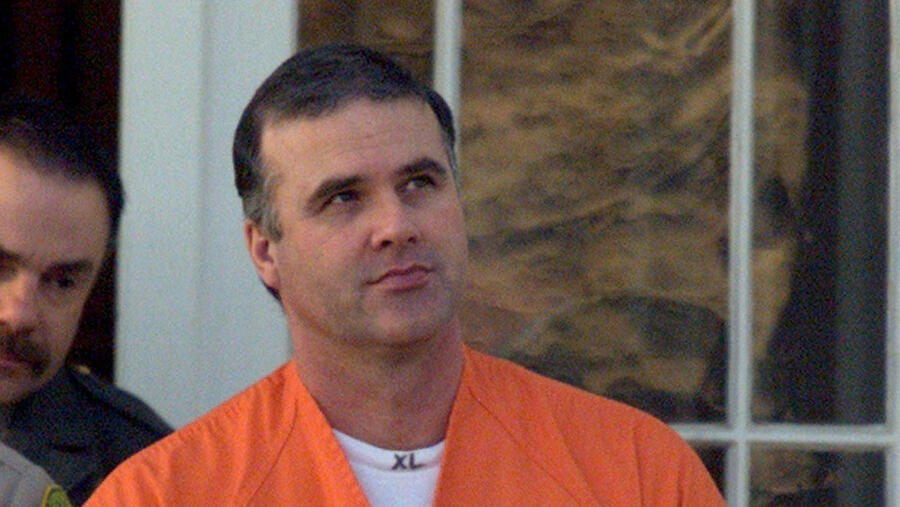

The Federal Bureau of Investigations turned their attention to Cary Stayner—a handyman who was working at the motel where three of the victims had been staying—when an eyewitness reported seeing his pale blue 1972 International Scout near his fourth victim’s house on the day of her killing.

Shortly after Stayner was detained, he told his arresting agents over pizza he would confess to the murders—but only if they would provide him with a sizeable collection of child pornography. Stayner didn’t get his wish, but he confessed to the killings anyway.

Stayner was convicted on August 27, 2002 of four counts of first-degree murder, and sentenced to die at San Quentin State Prison in California. But California’s last execution was held in 2006, and in 2019 Governor Gavin Newsom placed a statewide moratorium on capital punishment.

Cary Stayner’s Life Before His Arrest

Unlike many of the world’s most gruesome criminals, Stayner had virtually no criminal background prior to his killing spree; a habitual marijuana smoker, he had only been previously arrested on low-level drug possession charges.

But even though he hadn’t run afoul of the law much, Stayner had plenty of violence in his background.

[Stream Invisible Monsters: Serial Killers in America on A&E’s site and apps.]

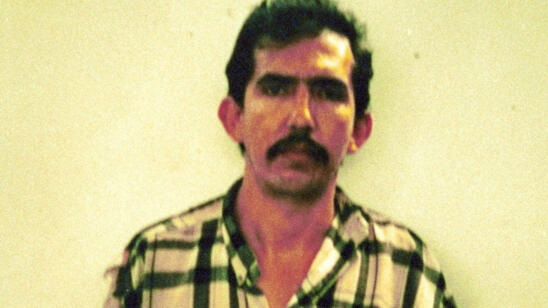

Most notably, Stayner’s younger brother Steven Stayner was kidnapped from a mall in 1972 near the Stayner’s Merced, California home. Steven at the time was 7. Cary was 11. About eight years later, Steven escaped—a story that drew significant media attention and was turned into a popular television miniseries, “I Know My First Name Is Steven.” But in 1989, Steven died in a motorcycle accident at the age of 24.

At time of Cary Stayner’s trial, stories regularly noted the high-profile abduction of his brother. But a psychiatrist who evaluated Cary Stayner isn’t convinced that Steven’s kidnapping led to Cary’s urge to murder.

“There’s no doubt [Cary Stayner] had a troubled childhood,” says Fred Berlin, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine who specializes in sexual offenders. “But it wasn’t just the thing about his brother.” Instead, Berlin says that child abuse was likely a stronger factor in warping Stayner’s psyche, noting that Stayner was sexually molested by an uncle.

“Many children who are sexually abused are damaged in their sexual development,” Berlin tells A&E True Crime.

Berlin also notes that while Stayner took obvious pleasure from “non-consenting sexual acts,” attempting to rape one of his victims, he wasn’t a sadist in the traditional sense. Stayner’s paraphilia wasn’t rooted in the enjoyment of his victim’s anguish so much as it was in the enjoyment of successfully controlling his victims by force.

“A sadist is aroused by the pain, suffering and fear of the victim,” Berlin says. “A sexual sadist might burn their victim, leave bruises… It’s about the maximum amount of suffering. He wasn’t like that… There are people who are aroused by coercive sexual behaviors, but they are necessarily aroused by seeing the pain of the victim.”

Where Is Cary Stayner Now?

Since his arrest, Stayner, now in his early 60s, has been held at San Quentin State Prison on death row. San Quentin is California’s oldest prison and has the largest death row in America. High-profile killer Scott Peterson is also being held there.

According to Daniel Vasquez, a former warden at San Quentin, the prison is also an exceptionally difficult place to live.

“When I first arrived [in 1983], it was under litigation for cruel and unusual punishment,” says Vasquez. More recently, the prison was fined hundreds of thousands of dollars for its poor health standards during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, more than 2,200 of the prison’s 3,300 inmates tested positive for the virus. As of February 2021, 28 inmates died from the disease.

But San Quentin’s widespread COVID-19 outbreak reflects the prison’s unsanitary conditions more than its overcrowding. For death row inmates like Stayner, life on San Quentin’s death row is one of profound isolation. According to Vasquez, everyone on death row lives alone in single cells, which are each approximately 48 square feet each—approximately 10 percent larger than the footprint of a king-sized bed. The condemned men are entitled by law to 10 hours of exercise in the prison courtyard.

But other than outdoor exercise and the occasional attorney visit, Cary Stayner is trapped inside his cell.

Related Features:

An FBI Agent Recounts a Repulsive Request by Serial Killer Cary Stayner During His Interrogation