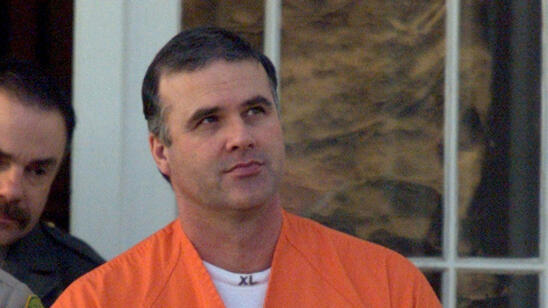

Throughout his 30-year career with the FBI, Special Agent Jeffrey Rinek became known for pulling out confessions from the worst criminals, including serial killers like Yosemite Killer Cary Stayner.

Stayner—whose young brother Steven was abducted as a child and later received nationwide attention through the TV miniseries, “I Know My First Name is Steven”—murdered two women and two teenage girls near Yosemite National Park in 1999: Joie Armstrong, Carole Sund, Juli Sund and Silvina Pelosso. He admitted his grisly crimes while being interrogated by Rinek.

In Rinek’s new book, In the Name of the Children: An FBI Agent’s Relentless Pursuit of the Nation’s Worst Predators, he offers an inside look at some of his biggest investigations against child predators.

In the excerpt below, reprinted with permission of BenBella Books, Rinek recounts the immediate aftermath of Stayner’s confession.

Please note, the following content contains disturbing accounts of violence and sexual violence. Discretion is advised.

It was just Stayner and me alone in that interview room and he had dropped a bombshell, claiming responsibility not just for the killing of Joie Armstrong but also for the murders of Carole and Juli Sund and Silvina Pelosso. But now he was imposing conditions for his cooperation. I asked what he wanted. He spoke obliquely, like he didn’t want his request to sound as bad as it was.

“You work all kinds of cases,” he began, hemming and hawing as if he wanted me to fill in the blanks, like he did when he wanted me to guess what cases he was referring to when he said he could give me closure. Eventually he got around to the point. “I’d like to see pictures of little girls.”

“Child pornography?” I asked, incredulous.

He wouldn’t call it what it was, just said again, “You know, pictures and videos of little girls.” He said he thought we might have such evidence stored in the building.

I could feel anger rising up inside me. I had felt a bond of trust and empathy growing between Stayner and me. He had allowed me to glimpse some of both the pain and the ugliness roiling inside him and had made the decision to reveal to me the terrible secrets he had been carrying so I could stop him from killing again. By putting conditions on his confession now, I worried that Stayner’s motivation was not about “giving closure” and telling the truth because it was the right thing to do. Instead, it looked like he was seeing what he could get out of us—and not just something like a plea bargain, which would be understandable, but something so base and unspeakable even he couldn’t say the words.

I needed to tamp down my own emotions and concentrate on the task at hand. Perhaps Stayner was still testing me, seeing if I would recoil in judgment of him. Or perhaps it was a battle for control, as serial killing and sexual assault are very much about control and dominance. Or perhaps it was even sadder, a last chance to satisfy a desperate craving. Whatever the reason, Stayner was asking me to do something illegal and unethical—to commit a crime to solve a crime—and I wasn’t about to do that. But there we were, on that precipice, and I didn’t want to risk him slipping from our grasp. I didn’t know if we had any evidence against him and I worried that this could be our only chance to get a very dangerous man off the streets. I told him I had no authority to grant his request and I would pass it on to a higher authority.

I went out to talk to Hitman (my partner and acting FBI supervisor, Ken Hittmeier) and he was taken aback as much as I was by Stayner’s demand. He said he would pass it up the chain of command, but neither of us could imagine any scenario under which we could show Stayner such material. We would have to appeal to the “good Cary” I had already glimpsed, who was now in a final desperate battle with his dark side. Hitman suggested we move the interview to the polygraph room, which had recording equipment and a two-way mirror through which he and others could monitor the interrogation. Harry Sweeney had already set up in there for the polygraph before Stayner called it off, and we had Harry remove all his equipment, then brought in Stayner. I decided we would eat lunch first to buy some time to get our heads together. When John brought in the pizza we had ordered I asked Stayner if it was OK for John to join us and he agreed.

I invited John to stay not only because he is a great agent but also because he was a good friend and I feel more comfortable in a high-stakes situation like that with someone I trust. I wasn’t in there alone anymore. John was in the room with me. Hitman and Harry were on the other side of the glass and at breaks I would go to them for guidance. I felt particularly good about having Harry looking over my shoulder because he is an expert at detecting when someone is not being truthful. Interrogations are so nerve-wracking and emotionally draining that it is hard to maintain focus at all times. So even though I was taking the lead, it was important to have others around to challenge my own assumptions, pick up on mistakes I might make, bring their own insights, and point out things I might overlook. We had a big day in front of us, but we would get through it together.

As John and I ate lunch with Stayner he began to get morose, aware he was potentially setting himself up for execution.

“This is gonna be my last pizza,” he said. I tried to buck him up, told him he was a long way from that day, should it ever come. “Never got to see Star Wars,” he continued, as random thoughts of things he enjoyed in freedom began popping into his mind.

I tried to assure him that not only would he be giving a gift by telling the truth but also that he would be getting something in return: relief.

“You’re going to feel good,” I said. “Not good,” I corrected myself, “but you’re going to feel peaceful—probably a feeling you haven’t had in a long time.”

“It means I can die with a clear conscience now, whenever that day comes,” Stayner said. “I know they’re going to give me the death penalty. Even if I confess, they are going to give me death.”

I promised Stayner I would be there for him as long as it took, as far as it went. I asked him to stop and think about how what he was doing now was as close as he could come to giving life back.

“It’s weird because I love life so much,” he said, without a hint of irony. One minute, he said, he’d be enjoying time with friends, marveling at nature, and thinking high-minded thoughts, “and the next minute it’s like I could kill every person on the face of the earth.”

“It just mentally tortures you,” he went on to say, “constantly back and forth like a tennis match.”

“But this is over now,” I told him. “You have taken control today. You are controlling you, probably for the first time since you were eleven.”

I asked him if his family knew about the tremendous internal issues with which he was struggling. He said he had never told anyone until now, not even his closest friends.

“Well, don’t you think it’s time we dealt with this and get rid of these demons?” I asked him. In the end, I said, “Whether I live longer than you or you live longer than me, we’ll both know we did what we thought was right and we took control, and that is the bottom line.”

His anguish was palpable. He had first started imagining scenarios of harming women and girls when he was just six or seven years old. The thoughts were alarmingly sadistic even at a young age—he imagined having a neighbor girl trapped in an underground bunker when he was just eight—and became only more so as he grew older. He was thirty-seven now, and for over three decades a war had waged inside him.

The thoughts and fantasies that consumed him preceded his brother Steven’s kidnapping, when Stayner was eleven, and his own sexual victimization by his uncle, which happened about six months thereafter. Those experiences certainly were damaging and poured fuel on a fire that had already begun to smolder as Stayner grew up in an environment rife with dysfunction and twisted sexuality. According to a psychiatrist who would later evaluate Stayner for his defense team, the Stayner family tree was riven with mental illness and sexual abuse going back five generations. According to the psychiatrist’s report, Stayner’s father, Delbert Stayner, was ordered into therapy for molesting his own daughters. In addition to her father’s unwanted advances, one of Stayner’s sisters said that Cary started peeping on her and inappropriately touching her when she was ten. A cousin said that Stayner spied on her and his sisters and a neighbor girl, hiding under their beds and secretly videotaping them in the bathroom and bedroom. One relative described child sexual abuse as “like a family sickness” because it had been going on for so many generations.

The fact that Stayner’s brother was kidnapped by a pedophile and abused for seven years adds an almost unfathomable dimension to the tragedy that enveloped this family. As the older brother, Stayner felt a natural if undeserved sense of responsibility for not protecting Steven from harm. He also felt more directly responsible. Stayner told another psychiatrist, Park Dietz, who was hired by the prosecution to evaluate whether he was sane at the time he committed the Yosemite murders, that as a child he worried that the obsessive thoughts he had about holding the neighbor girl against her will somehow caused Steven to be kidnapped.

Stayner’s parents would testify at trial that they both withdrew emotionally after Steven went missing. Delbert swung between all-consuming efforts to find his missing son and suicidal depression. He was so bereft when Steven was taken that he pushed Cary away, saying his “real son” was gone. Stayner’s mother, Kay, said her own father had told her to view Steven’s kidnapping as a good thing because now she had fewer kids to worry about feeding and clothing. She said her father insisted she never cry or show emotion because it would make her appear “crazy” like her mother, and that she had raised her own kids with the lack of emotional warmth her father inculcated in her.

Despite it all, Stayner loved his family and knew that what they were about to learn about him would destroy them. He started putting other terms on the confession. He wanted his family to get the $250,000 reward the Carrington family had offered, and he wanted to be housed in a federal prison being built near his hometown of Merced. John and I told him that those latter two requests were completely out of our hands. The distribution of the reward was not up to the FBI but the Carrington family (and I could imagine no scenario in which they would agree to pay it out to the killer’s own family). Nor could we ensure which prison Stayner would be sent to if convicted because, although the Armstrong case had federal jurisdiction because the murder was committed in a national park, the Sund-Pelosso case was a state matter. We knew we couldn’t deliver on any of his demands and tried to get him to prioritize what was really important to him. But he kept reiterating that the porn was his number one request and, in fact, a deal breaker. He even got particular, saying he didn’t want to see just a few stills but a big stack of pictures and especially videos.

I excused myself to talk with Hitman about what had just occurred. I also needed a little time to cool off. I called Lori and told her that I had no idea when or if I was going to get home that night. I told her that I was either on the verge of getting the biggest confession of my career or about to screw it all up.

Excerpt from In the Name of the Children: An FBI Agent’s Relentless Pursuit of the Nation’s Worst Predators, by Jeffrey L. Rinek and Marilee Strong, reprinted with permission of BenBella Books, Inc. Copyright 2018 by Jeffrey L. Rinek and Marilee Strong.

Related Features:

Connecticut Serial Killer William Devin Howell Describes the Shocking Details of His Crimes

What Can You Do if a Registered Sex Offender Moves Into Your Neighborhood?

Do All Serial Killers Have a Victim ‘Type’?