After fleeing authorities and fighting quadruple murder charges, Christian Longo eventually

acknowledged that he slaughtered his entire family.

“I am guilty,” Longo wrote in a March 5, 2011 New York Times op-ed, almost eight years after being sentenced to death for the crimes. “I once thought that I could fool others into believing this was not true. Failing that, I tried to convince myself that it didn’t matter. Gradually, the enormity of what I did seeped in…followed by remorse and then a wish to make amends.”

Longo’s idea of amends was donating his organs after execution. His views renewed a national debate over the issue. But can convicted murderers actually donate organs?

It’s extremely rare, according to experts.

“There are ethical issues and there are logistical issues,” United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) spokeswoman Anne Paschke tells A&E True Crime.

Gary Gilmore’s Eyes…and Other Organs

The U.S. Department of Prisons prohibits donating organs posthumously, and individual states typically don’t allow the practice. But exceptions did occur in the 1970s and ’80s with convicted murderers Gary Gilmore and Margie Velma Barfield.

Gilmore gained infamy as the first person executed in the U.S. after the death penalty was reinstated by the Supreme Court. He requested a firing squad.

In and out of prison most of his life, Gilmore went on a rampage in Utah following a breakup with his girlfriend. He fatally shot two young Mormon men in back-to-back heists in July 1976, but was caught and convicted within months.

After his January 17, 1977 execution, Gilmore’s body was taken to Utah University Medical Center, where doctors removed his organs. He had specified his pituitary gland, liver, eyes and kidneys be donated; however, his kidneys were too damaged, according to a January 18, 1977, Associated Press account.

Later that year, punk rock band The Adverts scored a hit with “Gary Gilmore’s Eyes,” about a fictional recipient of the killer’s corneas, but it’s unclear if his organs actually found their way to donors.

“It doesn’t sound like a firing squad [execution] would be compatible with organ donation,” Paschke says.

Poisoner’s Organs Donated

South Carolinian Barfield’s road to death row started when an autopsy showed that her boyfriend, Stuart Taylor, had died of arsenic poisoning in 1978. Investigators later linked Barfield to the poisoning deaths of her mother and two seniors she was caring for, though she was never charged for their murders.

Defense attorneys said Barfield was under the influence of painkillers when the crimes occurred and didn’t comprehend her actions. But she was convicted of Taylor’s murder and confessed to the three others.

North Carolina authorities executed Barfield, 52, by lethal injection on November 3, 1984, making her the first woman to face capital punishment in the U.S. since 1962.

”I am sorry, and I want to thank everybody who have been supporting me,” she said in a statement.

Barfield’s body was transported to a medical school and the organs she had agreed to donate were removed, The New York Times reported.

Don’t ‘Waste’ My Organs

More recent attempts by convicted murderers to give organs after death have been stymied.

After racking up gambling debts, Georgian Larry Lonchar fatally shot father and son bookmakers Charles and Steven Smith in October 1986 along with a female friend, whom he stabbed repeatedly.

Lonchar was sentenced to death via the electric chair, but in 1995 his lawyers sought an alternative means of execution so his organs could be viable.

“My life is nothing. I’m not afraid of dying,” Lonchar said. “If I can make my life a little worthwhile, then I’d like to.” A judge denied the request and Lonchar was executed on November 14, 1996.

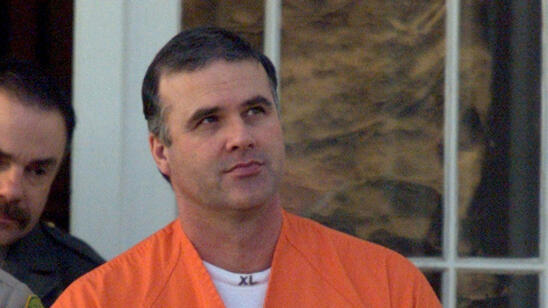

Amid marital and financial problems, Christian Longo strangled his wife, Mary Jane, and youngest daughter, Madison, 2, in mid-December 2001, according to court records. He also killed his 4-year-old son Zachery and daughter Sadie, 3, by asphyxiation, authorities surmised, and disposed of the bodies in waterways near the Oregon coastal town where they lived.

Longo fled to Mexico and was arrested in January 2002.

Although admitting he strangled his wife and Madison, Longo blamed Mary Jane for murdering the two eldest children. A jury wasn’t convinced and convicted him in 2003.

In March 2011, Longo wrote, “I am 37 years old and healthy; throwing my organs away after I am executed is nothing but a waste. ”

Oregon Governor John Kitzhaber, however, issued a death penalty moratorium in late 2013, making his arguments moot.

Long Odds

There are nearly 107,000 people waiting for an organ transplant in the U.S., according to UNOS.

But “there will always be questions when it comes to organ donation involving death row prisoners— whether their offer to donate an organ is truly voluntary,” Death Penalty Information Center Executive Director Robert Dunham tells A&E True Crime.

“There are also questions as to whether the offer to donate is genuine or is an attempt to delay a pending execution,” Dunham explains.

Just by the numbers, “a very small fraction of people die in a way that makes them a potential organ donor,” Paschke says. “You need to be in a hospital on a ventilator. Once that oxygenated blood stops pumping to the organs, they’re not viable for a transplant anymore.”

It’s also worth noting that doctors don’t participate in executions, and that prison life can cause infections that affect the eligibility of donors, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

“It does take that buy-in from a lot of stakeholders for this to happen,” trial lawyer Amanda Kay Seals, who has written on the topic, tells A&E True Crime. That includes cooperation from state departments of corrections, wardens and medical teams for both donors and recipients.

Seals argues that stigmas against prisoner organ donations not only can prevent an obvious benefit to people seeking a transplant, but for inmates “it’s an opportunity to exercise agency for good in an environment where there’s very little opportunity to exercise agency at all.”

‘Under the Radar’

Some death row inmates have tried to donate organs while living.

Delaware brothers Steven and Nelson Shelton were both sentenced to death for beating a man to death following hours of drinking in 1992. First, Nelson requested to donate a kidney to his mother, but they were found to be incompatible, and he was executed in 1995. Then Steven was approved as a donor and a viable transplant occurred in April 1995.

In 2013, Ronald Phillips tried to give a kidney to his mother, but was unsuccessful. The Ohioan had been sentenced to death after raping and fatally beating his girlfriend’s 3-year-old in 1993.

Governor John Kasich postponed Phillips’ scheduled execution for his request to be considered, but officials ultimately denied it and he was put to death in 2017.

Despite massive publicity over Gilmore’s execution, his organ donation went largely unnoticed, veteran Utah journalist Tom Haraldsen tells A&E True Crime.

“I think Utah County was in shock that this could have happened in their community—not so much the double homicide as the fact that his trial and scheduled execution was drawing so much national and probably international attention to their county,” says Haraldsen, who covered Gilmore’s crime spree. “His organ donations were pretty much under the radar. I don’t think many people knew about it or cared.”

Related Features:

Cooking Up the Last Meals of Death Row’s Most Notorious Killers