In the summer of 1969, Leslie Van Houten and Patricia Krenwinkel carried out horrific acts of butchery on the orders of charismatic cult leader Charles Manson—murdering a total of seven people over two consecutive nights.

At their murder trial the following year, lead prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi described the two so-called Manson women as “human monsters.” But to anyone who knew them growing up, they were bright, promising girls, seemingly incapable of such an unfathomable crime.

Award-winning journalist Nikki Meredith began visiting Van Houten and Krenwinkel in prison to discover how they had changed during their incarceration and what motivated them to commit such heinous acts under Manson’s leadership. She also met with a former high school friend, Catherine Share, who went on to become Manson’s chief recruiter of young women.

Below is an exclusive excerpt from Meredith’s book The Manson Women and Me: Monsters, Morality, and Murder, on sale March 27, 2018.

Catherine Share was an appealing dark-haired beauty in high school, and if I had voted on what she was most likely not to become, it would have been chief recruiter for a psychopathic serial killer. We were in the same social club at Hollywood High, and years later when I first heard her name associated with Manson, I assumed it was a different Catherine Share. When it proved to be the same person, I was sure she was on the periphery and if not on the periphery, then a reluctant participant in the activities of the so-called Family.

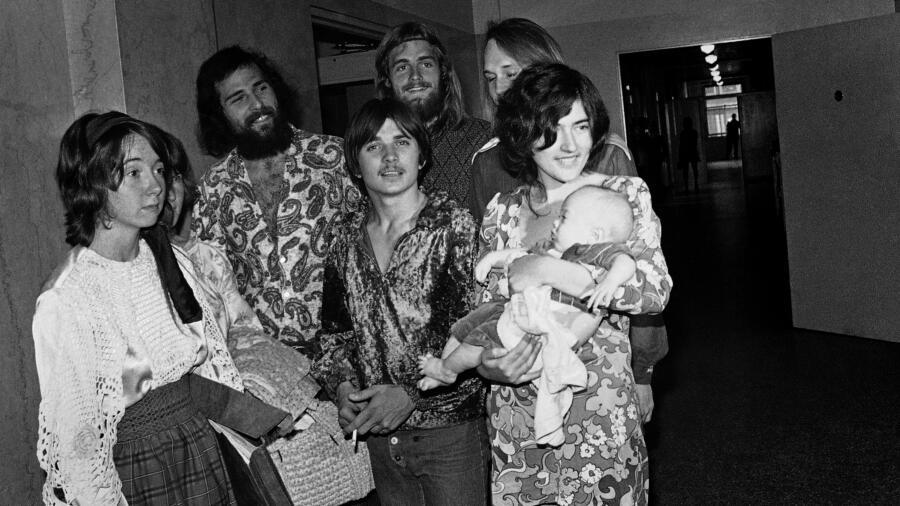

Leslie set me straight: there was nothing peripheral or reluctant about her involvement. She was an aggressive recruiter for Manson. Her primary quarry: pretty girls who could be used as bait to attract men into the fold and girls who had access to their parents’ credit cards. Although she was in the inner circle of the group at the time of the murders, Manson had not included her in his plan either night. She’s quoted on a website (manson2jesus.com) as saying she wouldn’t have participated in the murders even if Manson had asked her to, but there’s ample reason to doubt the validity of that claim.

What is not in doubt: after Manson was in prison, Catherine was a major aider and abettor on the outside, working assiduously and violently under his direction. Among her activities: an attempt to kill a witness and an attempt to rob a surplus store to steal guns. The most chilling, however, occurred in 1971 when she and several cohorts planned to highjack a Boeing 747 and kill one passenger every hour until Charles Manson, Tex Watson, and the three women were released from prison.

When I think of her at Hollywood High, I remember a quiet, restrained girl with ink-black hair and a distracted air about her. She was smart and talented with a pure singing voice, a violin virtuoso, and a beauty—though not the kind of conventional beauty for which Hollywood High was known. There was something slightly off kilter about her angular features, and that lack of symmetry only contributed to her beauty. Her name when she was with Manson was Gypsy—a name she acquired, I assume, because of her exotic looks.

How could that girl, a Jewish girl whose biological parents had died under Hitler’s reign, dedicate her life to a man who carved a swastika on his forehead? How could that same girl later marry a member of a white supremacist prison gang? This was not the behavior of a rebellious kid. She was a twenty-seven-year-old woman when she attached herself to Manson and a thirty-three-year-old woman when she married Kenneth Como, a member of the Aryan Brotherhood whom Manson met in San Quentin.

When Catherine Share and Leslie Van Houten were teenagers, though eight years apart, they shared many attributes—smart, pretty, popular—but when I ponder Leslie’s transformation from “prom queen to murderer,” I have to rely on my imagination to recreate who she was in high school. Catherine’s transformation was more astonishing and more upsetting for me personally because I did know her before. I wouldn’t have known the earlier version as well as I did, though, if it hadn’t been for our club’s slumber party when I was a senior and she was a junior.

There were many elements that came together to make that night remarkable for me. The house—a house so spectacular it could have been a movie set—was definitely one of those elements. It was located off of Mulholland Drive, a wealthy, wild area emblematic of Los Angeles, often used as a backdrop to movies. Also, it marked a time in my life when connecting with people who were different from my usual friends held a particular excitement. Unlike previous slumber parties, there were no crank calls, no lemon squeezes, no Ouija boards, no charades. We just talked, and Catherine and I talked a lot.

There was one more ingredient that made the night special. As I looked around at the girls in attendance, a small group of eight or ten, I realized that the narrow-minded culture of our club that had been a torment to me—a culture created by the older, all white, Protestant girls—had changed. My class was the first to rush and accept girls who were not WASPs. For me, that night reflected, if not celebrated, the shedding of what had been bad about the 1950s and embraced what was good about the 1960s.

When I discovered that Catherine was a kindred spirit—and when I say that, I mean when I discovered that she was Jewish—it was the first time I felt comfortable about my membership in the club. Until that moment, I had lived like a secret agent. The clubs at Hollywood High were patterned after college sororities and were so elitist and exclusionary the administrators were in a pitched battle to get rid of them.

I’ll admit the possibility that I projected more onto Catherine than was there, but that night she seemed to embody a depth and complexity that I admired and felt had been missing in my life, certainly in the club. Or maybe the intensity of my feelings was simply the result of having gotten lost on my way there. By the time I arrived safely I was so relieved, I loved everyone at that damn party and this certainly engendered an intimate connection with her. At least it did for me. I have no idea whether it was mutual. When we got together decades later in Dallas, Texas, I noticed a flicker of recognition when she first saw me. Was that flicker an acknowledgment of what we shared that night or simply an acknowledgment of the familiarity you feel with friends from high school? Either way, it was clear that whatever had existed between us was no longer there.

From THE MANSON WOMEN AND ME: Monsters, Morality and Murder by Nikki Meredith. Copyright © 2018. All rights reserved. Reprinted by arrangement with Kensington Publishing Corp.

Related Features:

What Was Charles Manson’s Childhood Like?