How did Charles Manson, an illiterate ex-con, become such an influential cult leader and turn a group of peaceful hippies into cold-blooded killers? Journalist Tom O’Neill set out to answer this question and more in his new book, Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties.

As O’Neill learned, it began with Manson’s troubled childhood. In this excerpt from the book, reprinted with permission from the publisher, we get a look at Manson’s early years—before he formed the “Manson Family” cult and commune—starting with his neglectful mother, then moving on to his stints in institutions for “delinquent” children and ultimately, in federal prison.

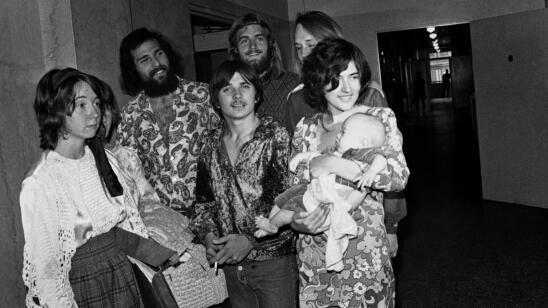

And this Charles Milles Manson, whose face was suddenly everywhere—was he not the epitome of the Dionysian thrill seeker? A thirty-five-year-old ex-con, roughly half his life whiled away in federal institutions, had ensnared the lives and minds of his followers, mainly young women. Numbering variously between two to three dozen, the majority of the Family members had been under Manson’s influence for less than two years, some not even close to that. Yet all of them would do anything Manson asked, without question, including slaughtering complete strangers. He had cultivated extreme compliance.

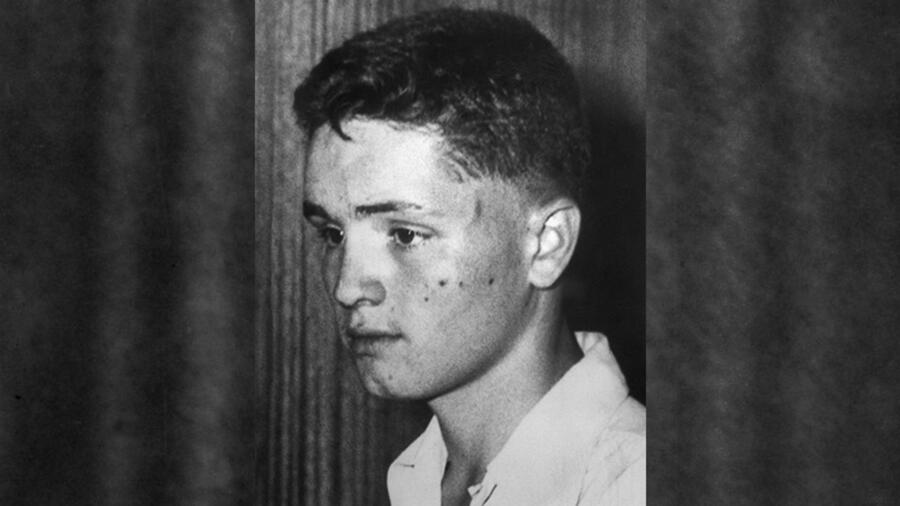

Manson was an unlikely candidate for a charismatic leader. Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, to a sixteen-year-old mother and a father he never met, he’d known little but privation and suffering. Few would be naturally inclined to look up to him, and in the most literal sense, not many could: he was only five foot six.

Manson spent his earliest years in neglect. When he was still an infant, his mother would leave him to go on benders with her brother, during one of which the pair decided to rob a guy who looked wealthy. Within hours, they’d been arrested, and Manson’s mother was imprisoned for several years. He was eight when she was released, and they spent the next months with a succession of unreliable men in seamy locales, his mom racking up another arrest for grand larceny. Eventually, she pursued a traveling salesman in Indianapolis, marrying him in 1943 and trying to cut back on her drinking. Manson, not yet nine, was already a truant, known to steal from local shops. His mother looked for a foster home for him. Instead, he was made a ward of the state and sent to the Gibault School for Boys, a Catholic-run school for delinquents in Terre Haute, Indiana. He ran away. His mother took him back. The separation must have weighed on him, at least to go by his acolyte Watson, who later wrote that Manson had “a special hatred for women as mothers… This probably had something to do with his feelings about his own mother, though he never talked about her… The closest he came to breaking his silence was in some of his song lyrics: ‘I am a mechanical boy, I am my mother’s boy.’ ”

The “mechanical boy” made short work of the Gibault School. Ten months in, he ran away again, turning to burglary to keep himself afloat. His crimes soon landed him in a correctional facility in Omaha, Nebraska. He ran away from there, too, and started breaking into grocery stores. At age thirteen, Manson was sent to the Indiana Boys School, a tougher institution, where he claimed the other boys raped him. He learned to feign lunacy to keep them at bay. And he kept running away: eighteen times in three years.

In February 1951, when he was sixteen, Manson broke out again, this time with a pair of other boys. They drove a stolen car across state lines—a federal offense. When a roadblock in Utah brought their escapade to an end, Manson was sent to the National Training School for Boys, in Washington, D.C. Thus began a long stint in the federal reformatory system. From there, Manson went to the Natural Bridge Honor Camp, where he was caught raping a boy at knifepoint; to a federal reformatory in Virginia, where he racked up similar offenses; and to a reformatory in Ohio, where a run of good behavior earned him an early release in 1954, though caseworkers had taken frequent note of his “antisocial behavior” and “psychic trauma.”

In less than a year’s time he had a wife, and a baby on the way. He took on various service jobs, but he couldn’t give up stealing cars, several of which he drove, again, across state lines. Those crimes, plus his failure to attend a hearing related to one of them, netted him a three-year sentence to Terminal Island, a federal prison in San Pedro, California. By the time he got out, in 1958, his wife had filed for divorce, and he turned to pimping to make a living. The following May, he was arrested yet again, this time for forging a government check for $37.50. This got him another ten-year sentence, but the judge, moved by the plea of a woman who said she was in love with him and wanted to marry him, suspended the sentence right away, letting him go free.

Manson kept pimping, stealing cars, and scheming people out of their money. The FBI was surveilling him, hoping to bust him for violating the Mann Act, which forbade the transportation of prostitutes across state lines. They were never able to bring the charge, but when Manson disappeared to Mexico with another prostitute, he was found in violation of his probation, and the ten-year sentence he’d received earlier was brought into effect. The same judge who’d granted him probation now decreed: “If there ever was a man who demonstrated himself completely unfit for probation, he is it.”

Stuck in prison for the long haul, Manson took up the guitar and dabbled in Scientology. The staff noted his gift for charismatic storytelling and his enduring “personality problems.” He made no secret of his musical aspirations. From behind bars, he observed, with great interest and envy, the meteoric rise of the Beatles.

When he was released at age thirty-two, he’d spent more than half his life in the care of the state. He preferred life in prison, he said, so much so that he asked if he could simply remain inside. “He has no plans for release,” one report said, “as he says he has nowhere to go.”

Excerpted from the book Chaos: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties by Tom O’Neill with Dan Piepenbring. Copyright © 2019 by Tom O’Neill. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company. All rights reserved.

Related Features:

What Was Charles Manson’s Childhood Like?

The 6 Most Bizarre Moments from the Manson Family Murder Trial

Charles Manson Would Have Made a Great Profiler and Other Surprising Insights from FBI Investigators

What Drove the ‘Manson Girls’ to Murder?

HISTORY: How Charles Manson Took Sick Inspiration from the Beatles’ ‘Helter Skelter’