For nearly two weeks in the spring of 1999, Londoners lived in fear, waiting anxiously to see when and where the next bomb would detonate—and who among them would fall victim to the explosive’s powerful blast or its high-speed nails and shrapnel.

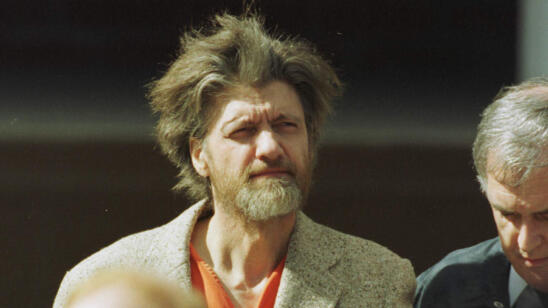

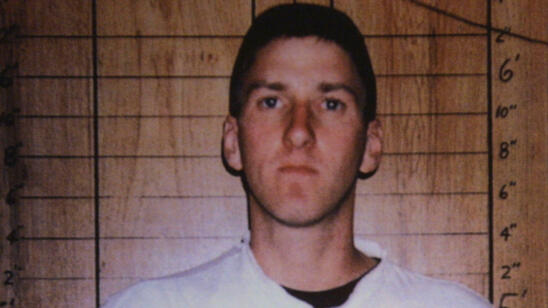

This period of terror was orchestrated by David Copeland, a 22-year-old lone wolf who police say targeted London’s Black, Bangladeshi and gay communities with homemade explosives. His goal? To incite a race war and spread fear and hatred throughout the country.

Copeland’s panic-inducing 13-day bombing spree came to an end on May 1, 1999, when police raided his home in Cove, Hampshire. There, they found explosive materials, Nazi flags and a wall of newspaper clippings about the attacks.

After grappling with questions about Copeland’s mental health and the extent to which he should be held responsible for his actions, a jury ultimately convicted Copeland of the bombings, which killed three people and injured 139, including a toddler.

Copeland, who is now 45, is currently serving out six life sentences in prison, with the possibility of parole around 2057.

The Three Bombings

Copeland, also known as the “London Nail Bomber,” became infamous for making and planting explosive devices in busy shopping areas on three days in April 1999. The first bomb exploded on April 17, 1999, at a market in Brixton, an area of south London with a large number of Black residents.

Packed with four-inch nails, the first bomb injured 48 people and began to arouse fears that someone was attacking the city’s non-white communities. Later, several racist groups fueled those fears by claiming responsibility for the attack, though authorities say Copeland acted alone.

A week later, on April 24, a second bomb injured 13 people in Brick Lane, home to one of London’s largest Bangladeshi communities. Police linked the two bombings and began treating them as racist hate crimes.

The third bomb went off on April 30, at a pub in the heart of London’s gay community, killing three—Andrea Dykes, who was four-months pregnant, Nick Moore and John Light—and injuring 79 people, several of whom later had limbs amputated.

David Copeland’s Early Life

Before he went on a bombing spree, Copeland was a troubled young person with extreme political beliefs and deep-seated anxiety about his sexuality.

The middle child of three brothers, Copeland grew up in Yateley, a town in Hampshire southwest of London. His father was an engineer and his mother worked part-time as an aide for people with disabilities.

Throughout his childhood, Copeland grappled with fears that his parents and relatives thought he was gay. He was convinced, for example, that when his parents sang the theme song to the “Flintstones” cartoon, they emphasized the words “we’ll have a gay old time” to send him some sort of message. He also refused to speak to his grandmother after she commented that he didn’t have a girlfriend and asked if he liked boys.

Even into adulthood, Copeland may have been confused about his own sexuality, which further fueled his homophobic beliefs and actions.

“Because the thought of being homosexual scared Copeland, his schizophrenic mind had him jump to the polar opposite, where he would project his insecurity as hate for homosexuals,” Holly Schiff, a clinical psychologist in Greenwich, Connecticut, who has followed Copeland’s case, tells A&E True Crime. “He hated homosexuals because he actually hated himself and couldn’t come to grips with his own sexual identity.”

He left school at 16 and began experimenting with alcohol and drugs, drifting from job to job. He had a few minor brushes with the law, including assault, theft and criminal damage, which his father chalked up to Copeland’s immaturity.

Copeland’s Pre-Bombing Descent

Copeland’s parents divorced when he was 19 and, after the attacks, they disagreed about the role their separation may have played in their son’s crimes. After the bombings, classmates remembered Copeland as introverted; his mother described him as “very, very gentle” and “never naughty.”

Copeland later told police he’d been having sadistic dreams since he was 12 and that he had thought about killing his classmates. He also said he’d been reading biographies of Adolf Hitler and had become fascinated with the idea of someday being famous.

Copeland told police he was initially inspired by the bombing attacks on the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. In 1997, he moved to London and joined the far-right British National Party. A year later, he joined the even more extreme National Socialist Movement.

He began researching bomb-making books and instructions on the internet, then set about buying the fireworks, alarm clocks nails and other materials he needed to build the bombs.

Copeland’s father, Stephen Copeland, said he believed his son simply got swept up in the political groups.

“I just believe he was easily influenced by people who saw they could indoctrinate him with their views. I just don’t believe he went looking for it himself,” Stephen Copeland told BBC News.

Experts say some people are drawn to extremist groups because they provide rigid, easy-to-understand rules for navigating the world. These groups also appeal to loners, introverts and people without much social support like Copeland, says Schiff.

“As humans, we like to avoid uncertainty or ambiguity,” she says. “Far-right ideologies emphasize order, familiarity, structure and a very rigid worldview.”

In 1998, Copeland’s doctor prescribed him anti-depressants to help with anxiety attacks; Copeland reportedly told his doctor he had “lost his mind.”

Later, Copeland’s mental health became a core issue during his trial. Defense psychiatrists diagnosed Copeland with paranoid schizophrenia and a personality disorder, which his lawyers used to argue that he should be found guilty of manslaughter, not murder, because his mental functions were diminished.

Jurors, however, refused to accept that argument and convicted Copeland on three counts of murder and three counts of causing explosions to endanger life. A judge sentenced Copeland to six life sentences.

“You set out to kill maim and terrorize the community,” said Judge Michael Hyam. “As a result of your wicked intentions, you have left three families bereaved. You alone are accountable for ruining their lives. Nothing can excuse or justify the evil you have done.”

Copeland may have been exaggerating his psychiatric symptoms all along. While awaiting trial, he wrote letters to a pen pal claiming that he had fooled experts about his mental illness.

Where Is David Copeland Today?

Today, more than 20 years after the bombings, Copeland continues to serve out his minimum 50-year prison term at HM Prison Frankland in Durham, England. In 2011, an appeals court upheld Copeland’s sentence and, in 2015, a judge added three more years to Copeland’s term after he attacked a fellow inmate.

In prison, Copeland has reportedly converted to Islam and has instructed other inmates to call him Saddam.

Based on his sentence length, Copeland isn’t eligible for release from prison until he’s in his 70s. And even then, a parole board must decide whether or not he still poses a risk to public safety.

“You never know what they’re going to do,” Michael Benza, a senior instructor of law at Case Western Reserve University, says of Copeland’s future parole board. “Time has a way of changing what we think of what a person did, or how bad we think what he did really is. It’s hard to imagine in Copeland’s case, but lots of things change. Politics change, society changes. And it depends on him, it depends on the victims’ families.”

Related Features:

A Ret. Bomb Technician Explains Package Bombs and Trip Wires Used in Austin Bombings

Bomb Squad Commander on ‘Pizza Bomber’ Scene Reveals Changes Made in Aftermath