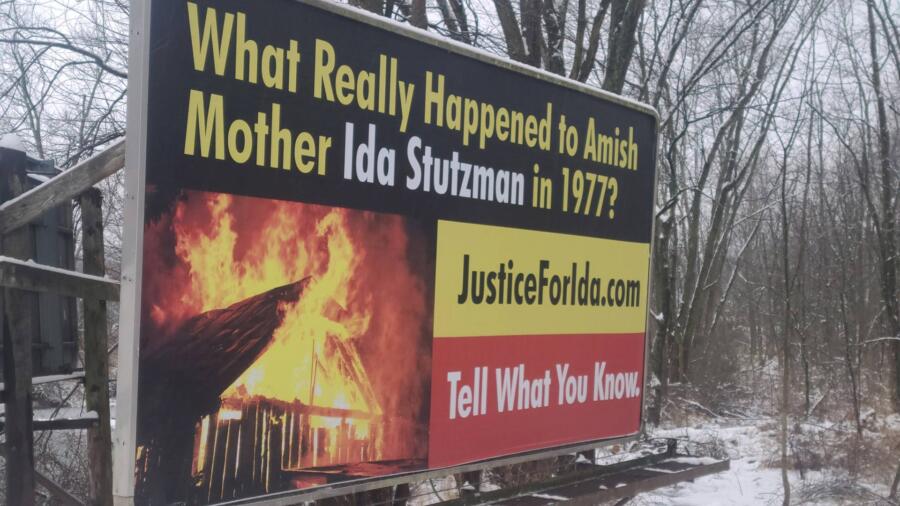

In July 1977, 26-year-old Ida Stutzman, an Amish woman, died as a barn fire raged at her farm in Dalton, Ohio. According to her husband, Eli Stutzman, Ida woke him just after midnight because of the fire. He told multiple people that Ida, who was pregnant, had wanted to save some milking equipment before going to a neighbor’s house to call for help.

That night, a neighbor helped Eli carry Ida’s body from inside the milk house by the burning barn. Eli claimed Ida had collapsed due to a bad heart—a condition Ida’s doctor would deny she had. The coroner ruled that Ida died of natural causes, and the sheriff didn’t investigate her death.

By 1979, Eli had left the Swartzentruber Order, the ultraconservative Amish sect he and Ida had belonged to. He moved around the country, along with his and Ida’s young son, Danny, as he used personal ads in The Advocate to find men looking for sex and relationships.

In December 1985, Eli abandoned 9-year-old Danny’s body in a Nebraska cornfield. Danny, who was wearing blue pajamas when he was found, would become known as “Little Boy Blue” in the media as authorities tried to figure out what happened to him.

Eli was eventually convicted of illegally dumping Danny’s body and for murdering a roommate, Glen Pritchett, in the spring of 1985. He served 15 years of a 40-year sentence and was released on parole in 2005. He died by suicide in 2007.

New York Times bestselling author Gregg Olsen interviewed authorities and people who knew Eli and Ida, to write about Eli’s crimes in his 1990 book, Abandoned Prayers. But he never forgot about Ida. Now, more than 30 years later, he has re-examined her death and whether she was an early victim of her husband. Olsen spoke to A&E True Crime about his new book, The Amish Wife: Unraveling the Lies, Secrets, and Conspiracy That Let a Killer Go Free.

What made you want to write this book now?

What started the book was when [Ida’s younger brother] Dan gave me a box of letters to look through—letters the family wrote to Eli, and [ones] he wrote back.

I interviewed [Ida’s parents] Amos and Lizzie Gingerich years ago [for Abandoned Prayers]. They’re [now] dead, [but] I think their whole lives, they knew. They knew their daughter had been murdered. They knew Danny had been murdered. And they knew that Eli was a liar. And it was probably enough for them to know that, because [they believed] God knew it, too.

Dan reached out to me [about Eli’s letters] because he’s [from] a different generation. He wasn’t his parents. And [after meeting him] I think he wanted justice from the world, too.

Did people in the Amish community have suspicions about Ida’s death?

I went back to Ohio to work on this book. I talked to people there that I had seen before [and] to a generation who didn’t know [Ida] directly, who were in their 30s. They all knew the story about the barn fire. And every single person that I talked to said they think that something bad happened that night.

Thirty years later, I think people were even more ready to talk and say that they were suspicious. Several people [mentioned] all of the lamps were on in the house during the fire. [Eli said Ida woke him] just after midnight. When you think about the calamity and the chaos of a fire, you’re not going to turn on all these kerosene lamps—you’re going to go out there and fight the fire.

The other thing that people were suspicious of was [Ida’s] clothing. They’d gone to bed [around] 9 o’clock, [but] she was [found] fully dressed in daytime clothes, [not] in a nightdress. But I know from my own experience with having a friend that was a Swartzentruber woman, [it takes] all this time to [use] straight pins to pin all your clothes together. It’s certainly not going to be [Ida] that gets [to the barn] first, like Eli [said].

Eli left the Amish in 1972, but returned in 1975, the year he and Ida got married. Did he come back because he wanted to marry Ida?

Eli had gotten into deep trouble when he faked his attack. [Eli had pretended to be a stabbing victim in November 1974 after he’d participated in a marijuana sting.] His only way out, I believe, was to return to the safety net of the Amish.

During Eli’s courtship with Ida, he continued to meet men [and] kept his driver’s license [a violation of his church’s rules]. He tricked her [when] he had the blood test faked. [At the time, Ohio required a blood test for syphilis and gonorrhea before people could marry, and Eli had to fake his test results].

[During the marriage,] Ida [told people she] was always left alone. This was not the action of a man who loved his wife.

Divorce isn’t accepted amongst the Amish. But if Eli wasn’t following the Ordnung, or strict Amish rules, would Ida have had an escape from the marriage?

[There was] no escape route. And [interviewing Ida’s family and friends made me] believe she loved Eli. She would have done anything she could to keep that marriage going and make him happy. She kept wondering why it was that she wasn’t enough for him.

Can you discuss how Eli seemed to have fabricated details about the barn fire and Ida’s death?

Ida’s doctor was on vacation when [the barn fire] happened. When he came back, he was stunned that Eli had told everybody that [Ida had a] bad heart. I interviewed him years ago, and he told me that Ida didn’t have a bad heart.

And [in 1978 Eli] writes a letter to [another Amish] widower in Indiana. He said, ‘Officials…claim lightning must have hit late that afternoon and just smoldered until that night.’ But he was the one who told everybody that [he saw] lightning strike the barn.

Why didn’t Ida’s family try to do more to protect her son after her death?

I think they were always worried and concerned, but there was nothing they could do. Danny was Eli’s son. And they’re not going to call the police or the sheriff because they want to handle things within their own world.

The Amish have their own set of beliefs they’re acting under?

That’s right. And it’s hard for us [non-Amish] sometimes to understand that. If, say, my sister died in a fire, and I thought that it was her husband who had done it, I would bang the drum loud and clear every single day with the sheriff, with the police. Because we know in our world that if we are out there complaining or calling attention to a case, [authorities] are going to have to do something about it.

The Amish did not have that ability to do any of that stuff because it was not allowed within their culture.

What do you want to result from revisiting Ida’s death after 30 years?

Part of the calamity of Eli’s life, and what he did to other people, it started that night. It started with [Ida’s death]. And he should have been stopped. If he had been stopped, the Pritchett family, little Danny Stutzman, [would] be in a lot better place.

I think there’s enough evidence in the book that the county should at least classify that death as suspicious or a potential homicide. They need to say, ‘This was a mistake in 1977.’

And I do hope that somebody out there who has another piece or two of the puzzle will come forward. Just because [Ida] was Amish doesn’t mean she didn’t deserve justice.

Related Features:

Why Did ‘Amish Stud’ Eli Weaver Plot to Have His Wife Murdered?

Child Sexual Abuse in the Amish Community: A Hidden Epidemic

Experts on the Twisted Reasons Why Some Husbands Kill Their Wives