In the fall of 2013, Americans were shocked to hear about the arrest of an elderly couple in their seventies, each charged with separate murders from decades prior.

Alice Uden (formerly Prunty) was charged with murdering her husband, Ronald Holtz, in the 1970s, and hiding his body in an abandoned mine shaft. Alice had gone on to meet and marry Gerald Uden, convincing him that his ex-wife Virginia was becoming a problem because of, among other things, her demand for more child support. Ultimately, Gerald became convinced the only way to keep Alice happy was to murder Virginia and his two young sons, Richard and Reagan—which he did.

Ron Franscell’s true-crime book, Alice & Gerald: A Homicidal Love Story, tells the story of this killer couple’s deep love and the dark secrets they were able keep buried for more than 30 years. In this exclusive excerpt, reprinted with permission of the publisher, we get a look at the initial police investigation into Virginia, Richard and Reagan’s disappearance.

The slow-starting investigation into Virginia and the boys’ disappearance began to heat up just as Wyoming’s long, frigid winter set in.

The sheriff sent seventy-five volunteers and deputies up to Dickinson Park to search for any evidence on the ground around the spot where the car was found. Problem was, that area was a popular picnicking and hunting site for locals, who might drop or discard a lot of junk. It’d be hard to separate meaningful evidence and meaningless crap.

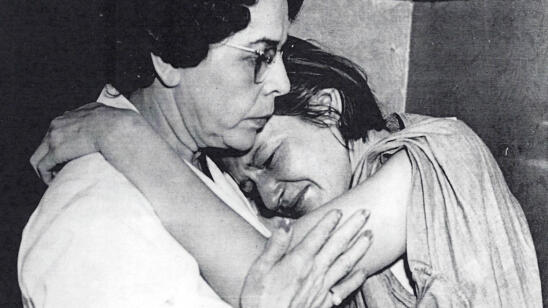

Nevertheless, Claire [Virginia’s mother] bought two shovels and joined the searchers. She’d offered to pay for any food or equipment the searchers needed, but the sheriff just waved her off. She wondered why the sheriff hadn’t mobilized a month earlier, when the weather was nicer and the scene was fresher, but she’d given up expecting brilliant police work from him.

It certainly didn’t improve her attitude when a volunteer asked to borrow a shovel. Or when she saw groups of searchers just standing around shooting the breeze for most of the morning. Not much actual searching seemed to be happening, Claire thought.

But somebody found a knife, some boys’ underwear, a sock, a piece of brown carpet, an old car mat, a pocket comb, a pile of cigarette butts, a kid’s left shoe, and an old brown furry coat. Every piece was catalogued, photographed, and stored.

Somebody showed the coat to Claire. It looked like one she’d bought and mailed to Virginia when she lived back East.

“Oh my God, that’s Virginia’s coat!” she said. “It’s gotta be!”

She tried it on, and it was the right size and color. Its dark brown fake fur seemed right. She knew she’d bought a coat that buttoned up, and it had buttons. It seemed like the same coat, but she couldn’t be absolutely certain.

It, too, was tagged and bagged.

It was time to have a heart-to-heart with the Udens. As the prime persons of interest, mainly because of the Mailgram and letters that seemed now to be deliberate red herrings, they had a lot to explain.

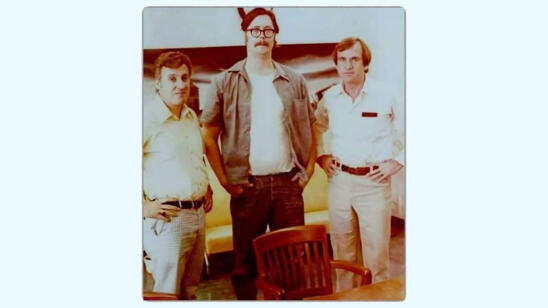

On November 14, Captain Larry Mathews called first Alice, then Gerald, to the sheriff’s office for interviews.

Although she wasn’t under arrest, Mathews read Alice her Miranda rights and had her sign a card that acknowledged she understood her rights. She didn’t want an attorney, she said, because she didn’t do anything.

The interview started at ten thirty that morning. The first questions were softballs and icebreakers, but Mathews quickly got to the meat of the matter.

“Did Virginia, at any time, indicate that she wanted more child support money?” he asked.

“No,” said Alice.

“Why did you instruct your daughter to write bogus letters to Claire?” “I thought Virginia and Claire were up to something,” Alice repeated from her earlier confession, “and I wanted to see what it was.”

“Why do you want to move to Oregon all of a sudden?” “It’s not sudden,” she said defensively. “My mom doesn’t like Wyoming and wants to live in Oregon, so we bought some land there. But my dad doesn’t want to move to Oregon, so the idea is tabled for now. Someday, maybe. Not now.”

“What was Gerald doing outside the laundry when he was arrested with a weapon?”

“Gerald is a different kinda guy. I don’t know what he was doing.” “Tell me about the day Virginia and her boys disappeared.”

“Gerald drove out to the corner and waited, but she didn’t show up,” Alice said. “So he came back in twenty or thirty minutes and started to work on our addition at the house. I went to town for groceries, and when I came back, it was still light out, but they still hadn’t shown up.”

Alice made a point of explaining that Gerald’s red pickup was broken

down that day, a bad oil pump. They only had her Pinto for transportation. “Would you take a polygraph test? A lie detector?” Mathews offered. Alice didn’t think long. “No. It’s just a matter of principle. Maybe I would if it was the last resort, but right now, no.”

“What would that be, the ‘last resort’?” Mathews asked.

Alice just shrugged.

“What do you think happened to Virginia and her sons?”

Alice shrugged again. “I have no idea,” she said, then launched into a scathing description of Virginia as a welfare queen, conniving ex-wife, detached mother, and all-around horrible person.

Throughout the interview, Mathews asked her several times to take a polygraph test, and she always refused “on principle.” On other questions, Alice would continually change the subject, rambling on about her two jackass ex-husbands, her kids, her many jobs, illnesses she’d had, places she’d lived, and other irrelevant topics.

Mathews, frustrated by Alice’s verbal camouflage, tried a different tack.

“Well, you wanna know what I think?” he asked. “I think you didn’t do anything but got caught up in the middle of things. You and Gerald knew you had to do something, so you took Virginia’s body and stuffed it somewhere, and you took her car up on the mountain and tried to conceal it and had Thea write that telegram to throw us off. Sound about right?” Alice looked as if she might cry, but stared teary-eyed into space. She’s thinking about how to word her confession, Mathews thought.

“I understand why you’d think like that,” she said, whimpering. “I know what you’re saying, but . . .”

But? But what?

“But I didn’t do anything,” she said, wiping her eyes.

After four hours of questioning, Mathews had hit a brick wall. He might have better luck with Gerald.

At the bottom of his last page of notes, Mathews wrote: “It was apparent to me—but only my personal feelings—that she was very guilty & covering up the issue. Almost broke at one time.”

So four days later, about three in the afternoon, Gerald sat down with Mathews in the sheriff’s interrogation room, the “box.” Again, Mathews read his Miranda rights, although he wasn’t under arrest. And again, Gerald refused to have a lawyer present. Mathews was relieved.

Gerald was a talker, all right. He couldn’t stop talking—about his job. Mathews let him talk for a while, then finally interrupted the meaning¬less blab.

“OK, Gerald, I brought you down here to talk about Virginia and the boys,” Mathews said.

“I’ve already told you guys the truth,” Gerald insisted. “I didn’t do anything wrong.”

As he’d done with Alice, Mathews laid out his theory: Gerald killed them all, hid them someplace, dumped the car, and tried to cover his tracks with bogus letters and Mailgrams from fake people.

Gerald hung his head and shuffled his feet. He crossed and uncrossed his lanky legs incessantly. He started shaking so badly he couldn’t talk for a few minutes. He oozed guilt.

Mathews poured Gerald a cup of coffee, more to agitate than calm him. Gerald sipped it with both of his trembling hands.

When he finally regained some composure, he had a perfectly logical Nebraska farm boy’s defense.

“You don’t really have a case,” he told Mathews, “because you don’t have a body or a murder weapon. Even if I did it—and I didn’t—you couldn’t arrest me because you got no body.”

As a legal scholar, Gerald was wrong. In 1960, the US Supreme Court ruled that a body (corpus delecti) wasn’t always necessary to convict a murderer if cir¬cumstantial evidence was enough to exclude any other “reasonable hypothesis.”

But as a country-boy lawyer, Gerald was right. A bloody murder scene, a motive, opportunity, and the victim’s complete vanishing might sway a jury, but a skillful defense lawyer can easily cast reasonable doubt on any theory because without a body, the prosecution can’t prove the victim is dead. So while no-body homicide prosecutions were legally per¬mitted, they were few as a practicality.

Mathews knew he was in a pickle.

“You could still be indicted for murder or kidnapping, Gerald,” Mathews said, but he knew it was a slim chance. “But if you’re innocent like you say, just prove it to me.”

“How?”

“Show me your innocence,” Mathews told him. “I’d just as soon prove you innocent as guilty. But you know we have to get to the bottom of this. Tell me something.”

Gerald said nothing.

“Do anything that proves you didn’t do it,” Mathews asked. It was starting to sound like begging. “Take a polygraph.”

Gerald shook his head. “No polygraph. It’s not about my guilt or innocence. It’s just a matter of principle.”

Mathews recognized that word “principle.” It was Alice’s argument against the polygraph. Gerald and Alice were getting their stories straight, even using the same words.

So Mathews moved on. He showed Gerald pictures of Virginia’s abandoned car, and he studied them closely.

“I thought you said someone tried to burn it up?” Gerald asked. “Yeah, it looked like that.”

“That would have been a dumb thing to do.”

“Why’s that, Gerald?”

“By looking at those pictures, you could see town below, and people could have seen the fire.”

Mathews glanced again at the crime scene photos.

“Gerald, you can’t see any town in any of those pictures you just saw.” Gerald looked again. Sure enough, no town.

“Well, I heard it on the news,” Gerald said defensively. “And I know where that’s at and I know you can see town. I go up there a lot.”

To Mathews’ knowledge, nobody had ever told Gerald exactly where the car was found. Maybe he heard on the street . . . or maybe he slipped again.

Gerald began to ramble nervously. He talked about contemplating suicide once and how that might solve his problems now. He talked about not liking jails and how he couldn’t possibly be confined in a small space for the rest of his life. He talked about how he tried to love Virginia, but she’d been bad to him. He talked about how much he loved those boys. He talked about how Alice hated Virginia, and vice versa.

Mathews let him run out of steam.

“Suppose you did kill Virginia and hid the boys somewhere,” Mathews theorized. “You must know that they will be found sometime and that you can never have them and raise them.”

Gerald seemed startled.

“Why can’t I?” he asked.

“You’d be tied into this mess because the boys would know if Virginia met you out there that day—which you say she didn’t.”

Gerald face went blank. “Not if they didn’t tell anyone . . . I never thought of it that way.”

Ninety minutes after it began, the interview was over. Gerald left and Mathews added a familiar postscript to his notes:

“It is only my personal feeling, but I could see guilt all over him. I am convinced he is guilty & is covering up.”

[Editor’s Note: Alice Uden died in prison on June 12, 2019 at the age of 80. Gerald Uden is still in prison and looking to be exonerated for the murders, claiming his wife conducted them.

Excerpted from Alice & Gerald: A Homicidal Love Story by Ron Franscell (Prometheus Books, 2019). Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

More Features:

Men Who Have Murdered for the Women They Loved

The Twisted Reasons Why Some Men Kill Their Wives

Casey Anthony’s Life Now, 10 Years After Daughter Caylee Vanished

Chris Watts Murder Case: The Most Disturbing Revelations from the Prosecution’s Discovery Files