In the popular narrative, spousal killings are crimes of passion. A soon-to-be-divorcee declares, “If I can’t have her, no one can.” Or: A husband comes home and finds his wife in bed with another man. He goes and grabs the baseball bat.

By contrast, financially motivated homicides are cold-blooded: the mafia, the silencer, the envelope full of cash.

But what about when these two ideas collide? What’s the motivation when a spouse kills their better half for money?

Gold digger killer cases are more common than you might think. David Adams, the author of Why Do They Kill? Men Who Murder Their Intimate Partners and the co-director of the anti-domestic violence nonprofit Emerge, estimates that “about 20 percent” of spousal killers are “materially motivated.”

According to Adams, spousal killers fall into five overlapping categories. In addition to the materially motivated, they are: the possessively jealous person, the substance abuser, individuals who are depressed/suicidal and the career criminal. Of those groups, it’s the materially motivated who most “try to get away with it.”

[Watch Deadly Wives on A&E Crime Central.]

“There’s a lot more preplanning,” Adams says.

A&E True Crime looks at some infamous killers who tried to make a quick buck putting their partners in the ground.

Uloma Curry-Walker

Cleveland firefighter Lt. William Walker thought he was cementing an eternal love when he married Uloma Curry-Walker at a small civil ceremony in the summer of 2013. But less than half a year later, Walker was gunned down in his driveway.

Unbeknownst to Walker, his new wife had accrued tens of thousands of dollars of credit card debt. Knowing that Walker had a $100,000 life insurance policy, Curry-Walker asked her 17-year-old daughter to help her plot his murder. They hired her daughter’s boyfriend, 20-year-old Chad Padgett, to do the job.

With the help of acquaintances Ryan Dorty and Chris Hein, Padgett carried out the deed on a $1,000 down payment. He was promised another $9,000 once Curry collected on Walker’s life insurance policy.

Todd Shackelford, a professor of psychology at Oakland University whose research focuses on intimate partner violence, says female killers are more likely to enlist outside help than their male counterparts.

According to Shackelford, this plays into a broader trend with female perpetrators of killing in a more calculated—rather than raging—manner.

“Women are much more likely to [plan their murders] over longer periods of time,” Shackelford says. “They’ll carefully think about it.”

For her part, Curry-Walker hadn’t thought quite carefully enough. Her payout never came because Walker hadn’t listed Curry-Walker as his insurance beneficiary. Instead, Walker’s ex-wife was the beneficiary on his life insurance—the result of the kill coming so soon after the marriage. Thus, she received the money instead of the person who organized his murder.

Curry-Walker’s conspirators turned on her, and for her deeds, Curry-Walker was found guilty of aggravated murder, conspiracy, murder and felonious assault. She received a sentence of life in prison without parole. For involuntary manslaughter with conspiracy, Padgett got 28 years. Dorty and Hein received 23 and 18 years, respectively.

Curry-Walker’s daughter, who was a minor at the time, was sentenced to a month in juvenile detention.

Des Campbell

As with Curry-Walker, Australian paramedic Des Campbell had only been married for half a year when his spouse, Janet Campbell, “fell” to her death at Royal National Park in March 2005.

At first blush, theirs is a romantic story: The pair met at the hospital where Janet was an orderly. She was also wealthy, having inherited a sizeable sum when her first husband died in 1997. But whereas Janet was enamored with Des—writing him into her will, putting both their names on a $660,000 property deed shortly after their wedding—Des was less enthralled. Behind her back, Des, a former police detective, called his new wife “pig ugly.” In their six-month-long marriage, Des had at least three extramarital affairs.

While camping, Des pushed Janet from a 50-meter cliff, crushing her against the rocks. He later claimed she disappeared after leaving their tent to relieve herself.

A few days after the murder, Campbell discussed Janet’s will and his new assets with his lawyer. He then used some of his windfall to book a vacation with another partner. Less than three weeks after the murder, he proposed to the woman.

According to Adams, the “materially motivated” category of killers includes a subset he calls “the serial exploiter of women.”

Having interviewed several such killers, Adams says these perpetrators are often “leading secret lives. They often have fabrications in their work records. They often have mistresses.”

And, he says, they often will kill their spouse less than three years after tying the knot. Murder/suicide spousal killers, by contrast, will commit the deed after an average of 15 years of matrimony.

Campbell’s callousness—combined with the testimony of a physics professor about the nature of Janet’s fall—was enough to convince a jury of his guilt. He was convicted of murder and sentenced to 33 years in prison.

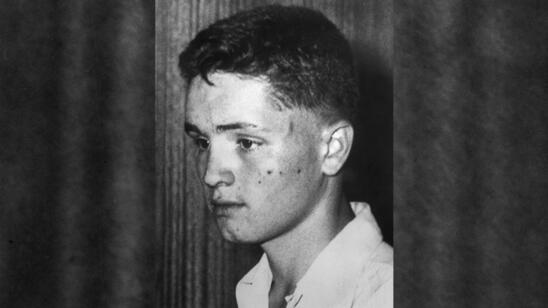

Charles Stuart

Some gold digger killer stories involve more than a husband and a wife—they’re entire family affairs.

That was the case with Charles “Chuck” Stuart, a Boston-area furrier who was shot with his wife, Carol, who was 7-months pregnant at the time, while parked in their car in the Mission Hill neighborhood of the city. Charles was shot in the stomach and Carol was shot in the head. Carol died shortly after her shooting. Doctors attempted to save her baby’s life, delivering him via Cesarean section, but the infant passed away 17 days later.

Originally, Stuart told police that the double homicide had been perpetrated by a Black male hijacker.

The 1989 shooting caused national headlines and caused a racially targeted manhunt in Boston, where multiple Black men were arrested and questioned in relation to the crime. Several lawmakers, swept up in the anger, demanded that Massachusetts reinstate the death penalty.

“They’re very media-savvy,” Adams says of killers like Stuart. “The media gets duped by them.”

But when it became clear that Charles was ready to positively identify one of the suspects, his brother Matthew Stuart came forward to police and confessed everything: He had disposed of Charles’s murder weapon on the night of the killing.

Charles Stuart had been having an affair, and was set to collect an $83,000 life insurance policy for Carol’s death.

Sensing his impending fate, Charles Stuart committed suicide by jumping off the Tobin Bridge on January 4, 1990, just hours after Matthew revealed the truth to the police. And while Charles left a note in his car saying his brother’s accusation “has beaten [him]” and that he was “sapped of [his] strength,” it didn’t contain a confession.

Related Features:

Why People Fake Their Own Death