In 2009, the FBI’s New York field office received the big tip they had been waiting for. The informer said Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, the world’s most famous drug lord, had hired a young technology specialist who had built the kingpin a sophisticated, encrypted cell-phone system.

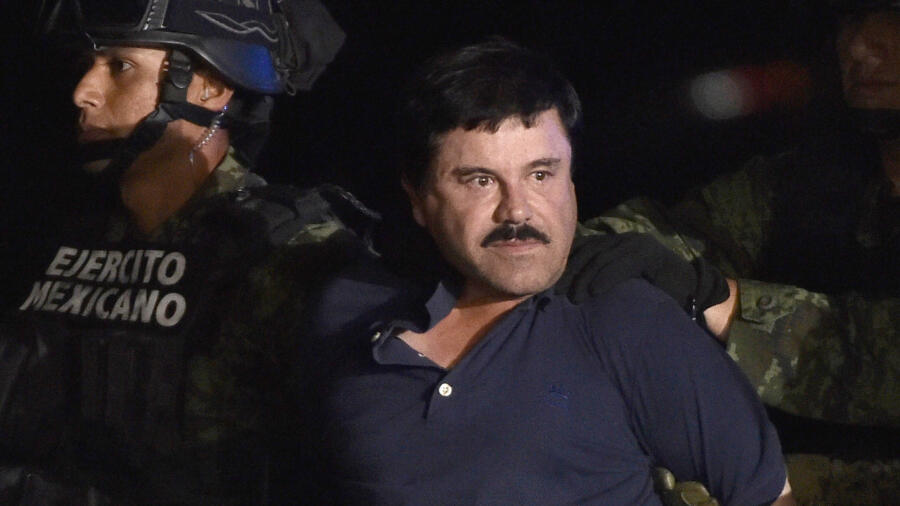

After multiple prison escapes through his more than 10-year reign, this would prove to be his ultimate downfall, causing Chapo to finally be captured by Mexican and U.S. law authorities, and sentenced in a Brooklyn courthouse. The leader of the Sinaloa-based cartel is now serving life in prison plus 30 years at the “supermax” ADX Florence in Florence, Colorado.

As Alan Feuer, a courts and criminal justice reporter for The New York Times, writes in his book about El Chapo, El Jefe: The Stalking of Chapo Guzmán, “[b]y wiretapping everyone around him,” he “accidentally wiretapped himself.”

A&E True Crime recently spoke with Feuer about Chapo’s public image, his decision to meet with the actor Sean Penn before his arrest and more.

From what you gathered from your reporting on the trial, what do you think Mexicans, in general, think of El Chapo? Is he, for some, a Robin Hood figure?

On the one hand, he’s without doubt a mass murderer, a corrupter of the government, has spent millions of dollars on bribes, perverting the system of justice in Mexico and acted with utter impunity over long periods of time. Many Mexicans recognize this tragedy and crime in every sense of the words. That said, you can’t deny that he also became a folk hero in the country—someone whom narco ballads were written about, who was celebrated as a kind of outlaw figure roughly equivalent to Jesse James in the United States. [Up until he was captured] he always got away with [his crimes] and poked his finger in the eyes of authorities.

There’s a reason he obtained that folklore status. In many places in Mexico, particularly Sinaloa, the local population had a long history of neglect and abuse by the government. Poor, rural regions of Mexico have traditionally been left behind by the powers that be in Mexico City and [its people] left to suffer, and be exploited by their government. And so, when a figure arises from poor, rural areas to [achieve] great success, and is able to constantly show up the government, it creates a kind of familiarity and even love among the population.

A standout narrative from the book is how the FBI tracked Chapo by coercing a technology guy who worked for him.

It was met with a little skepticism at first, [but] the FBI set about finding this young IT guy, and they did. He was Colombian; they found him in Medellín. They investigated him and ultimately approached him in the Bogota airport. They got him to cooperate [by] acting as a spy against Chapo.

[El Chapo and the cartel] were all using Blackberries with a spyware called FlexiSPY: a very powerful tool that allows you to collect info from targets, people that [Chapo] is selling to on calls, and even GPS location of where they are at any given minute.

So, Chapo had his IT guy infect a bunch of Blackberries and he passed them out to his wife, his ex-wives, his many mistresses and several of his key inner-circle staff members—like his lawyer and security chief. And unbeknownst to Chapo, the young IT guy was turning over all of the data that was being collected on him to the FBI. So, it was an unbelievable twist of irony: Chapo, by wiretapping all these people close to him was, in essence, wiretapping himself, because the information he was collecting as a spy was going out the back door to the FBI.

To what degree do you think the Sean Penn Rolling Stone article, where the actor secretly interviewed Chapo, played a role in the fugitive’s downfall?

If you talk to American law enforcement officials, they see the entire Penn saga—his involvement with Chapo, his trip to visit him in the mountains of Mexico—as a massive distraction [to their operation]. They see Penn as a fool who wandered into an ongoing surveillance and capture operation—and created a massive delay.

The U.S. government and the Mexican government had already pinpointed Chapo’s location in the remote mountains of Mexico, well before Penn showed up there to meet him. It’s not as if Penn led law enforcement to Chapo, in other words. I know there’s a narrative in which Penn was working with the American government to help track him. I found no evidence of that. His role was really kind of a distraction. It created a lot of problems because the U.S. government didn’t want to launch a raid on Chapo when Penn might be at the mountain compound. The Mexican government seemed to care much less if Penn was in the way when the Mexican Marines went up in helicopters and attacked the compound.

The [two] governments had a disagreement over how to proceed, which got very heated. But ultimately, the entire issue became irrelevant because a storm came in and made the raid impossible on the day it was supposed to take place. And by the time they got back together to do the raid, Penn and Kate del Castillo (who organized the interview between Chapo and Penn) were already on their way. The [authorities] launched the raid and missed Guzman—yet again.

What were your impressions of El Chapo during his trial in Brooklyn?

The trial itself was revelatory. I was concerned, going into [writing the book], that there would be nothing new to say about Chapo or his larger story, [which] has been told over the course of 30 years in books and TV shows and countless newspaper articles. But I was absolutely wrong, because the trial revealed the story of the Colombian IT person and the FBI’s attempt to spy on him. It revealed more about Chapo’s personal life. One of his mistresses took the witness stand. It just uncovered a mountain of new material that added to the saga.

A regular thing [Chapo] would do every morning, when he was brought out from his holding cell and placed at the defense table with his lawyer: He would go up on his tiptoes, look into the audience, find his wife, Emma, who came to visit him virtually every day, and give her a little smile and wave before he sat down. It was just a glimpse into the guy’s personality.

What do you think his motivation was for what he did in the end?

Obviously, money plays a role. Don’t forget, this is a guy who in his early 30s was making upward of $20 million a month. He loved the fame. He wanted to be bigger than Pablo Escobar, who was the last great narco trafficker in Latin America. But there was also a lot of evidence that [Chapo] was just a workaholic.

One of his first employees testified at the trial that [Chapo] never shut up about drug trafficking. He just loved it. He loved the details. He was a micromanager. Even when he went on vacation to his oceanfront mansion in Cabo San Lucas—supposedly there to have a good time, meet girls, eat seafood and lounge in the sun—American communications intercepts show he was on his Blackberry all day. He was working. He’s like one of these hedge-fund guys who can’t turn off. He just loved making the deal.

In the end, Chapo is in prison now and this time he won’t be getting out. But does that change anything when it comes to the drug trade?

The short answer is, it changes nothing.

Related Features:

El Chapo’s Trial: Why Mexican Drug Cartels Leave ‘Calling Cards’ With Their Murder Victims

Who Really Killed Pablo Escobar?

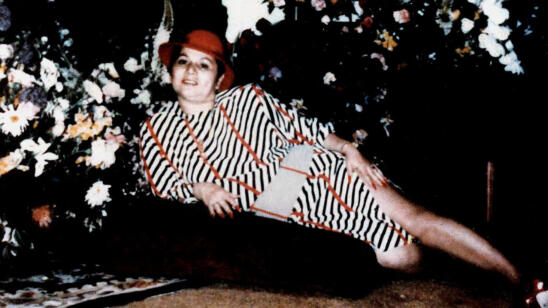

Griselda Blanco: A Blood-Thirsty Queen Among the Cocaine Cowboys