Warning: The following contains disturbing descriptions of violence and sexual violence. Reader discretion is advised.

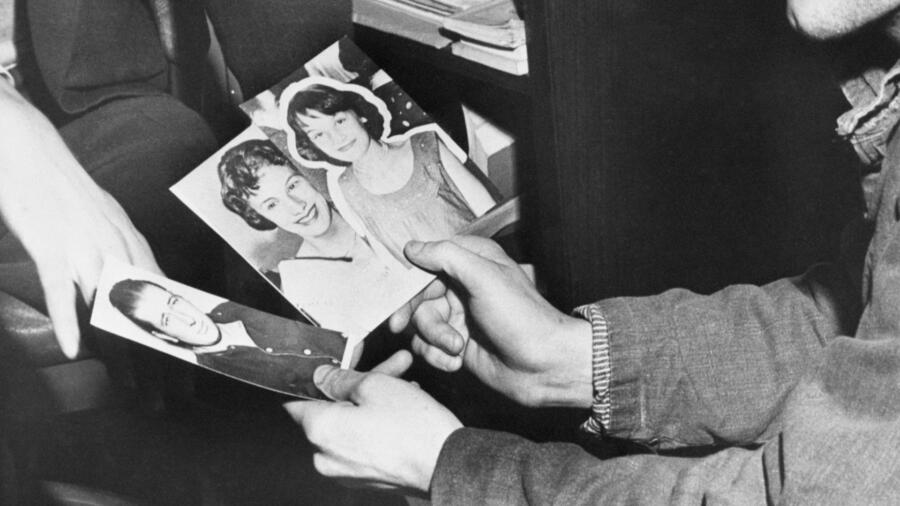

Six decades ago, the Grimes sisters Barbara, 15, and Patricia, 12, blithely left home to watch heartthrob Elvis Presley in Love Me Tender, at the Brighton Theater in Chicago.

The tearjerker ended with Elvis’s death in a shoot-out, the crowd filed out and the Grimes girls vanished.

Twenty-five excruciating days ticked by. “If someone is holding them, please let the girls call me,” their mother Lorretta Grimes pleaded, in a January 11, 1957 Chicago Daily Tribune (now the Chicago Tribune) article.

On January 22, 1957, their naked bodies were found in a field in a nearby suburb, with no signs of fatal violence.

The discovery horrified Chicagoans and the working-class Catholic neighborhood where the girls lived. With the public demanding answers, law enforcement went into overdrive, interviewing multiple suspects and filing charges—only to drop them for lack of proof as authorities feuded openly.

Now the notorious mystery is a footnote in the city’s history. Even so, the case is “still an open murder investigation,” a spokesman for Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart’s office tells A&E True Crime. “Our detectives work it as leads come in,” deputy press secretary Matthew Walberg says.

Love Me Tender

Like many 1950s bobbysoxers, Barbara and Patricia adored Elvis Presley. They’d seen Love Me Tender 10 times but begged their mother to let them catch the evening show at the local theater, just a short bus ride away. It was the Christmas holidays, December 28, 1956, and Lorretta gave her permission.

Barbara, a high school sophomore with a dazzling smile, was known as the “serious” one, and Patricia, or “Petey,” was a high-spirited seventh-grader. The two sisters were also close friends, former neighbor Melanie Forgala tells A&E True Crime.

[Watch Cold Case Files Classic on A&E Crime Central.

When the pair failed to return by midnight, Lorretta Grimes called the police.

As officers scoured the city, tips poured in. Workers at a Chicago five-and-dime store were positive they saw Barbara and Patricia with two sailors listening to Elvis records on January 3, 1957, according to the book Murder Gone Cold, by Tamara Shaffer.

A Minnesota woman, who was traveling, swore she met the sisters in a Nashville bus station restroom on January 9, 1957.

That account made headlines, spurring rumors the girls were headed to Memphis, Presley’s home. The singer himself issued a statement saying, “If you are good Presley fans, you’ll go home and ease your mother’s worries.”

Lorretta Grimes and her ex-husband, Joseph, insisted their daughters were in danger. “They are not the type of girls to run away,” Lorretta Grimes is quoted as saying in Murder Gone Cold.

Chicagoan Dominic Pacyga, emeritus professor of history at Columbia College, was seven when the sisters disappeared. “It was on everybody’s minds,” says Pacyga, who lived near the Grimes’s neighborhood.

“There were signs in the windows of stores saying, ‘don’t talk to strangers,'” he tells A&E True Crime.

‘They Didn’t Listen to Me’

On January 22, 1957, a passing motorist saw what looked like a mannequin off the bridge over Devil’s Creek near Willow Springs, a southwest suburb. Authorities converged and found the girls’ bodies, sprawled on the frozen ground.

“I tried to tell police my daughters didn’t run away, but they didn’t listen to me,” said Joseph Grimes, in a January 23, 1957 Chicago Daily Tribune article.

Patricia had several minor puncture wounds in her chest, possibly made by an ice pick, and Barbara’s face had marks and bruises, Harry Glos, the chief investigator for Cook County Coroner Walter McCarron, told reporters.

A preliminary autopsy, however, indicated the girls died of exposure to freezing temperatures.

The anticlimactic resolution with no evidence of traumatic violence amplified the mystery and renewed pressure on investigators.

Again, the public chimed in with tips. This included a cabbie’s description of seeing the sisters December 30, 1956, at a skid row diner located on Chicago’s hardscrabble Madison Street with two men, one reportedly with sideburns like Elvis.

‘If I Hadn’t Been Drinking’

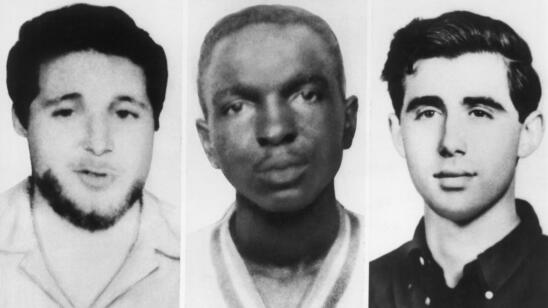

Police pursuing the diner lead tracked down a young drifter named Edward “Bennie” Bedwell from Tennessee. Bedwell, 21, was a former circus worker who had briefly served in the U.S. Air Force. He had jobs at a factory and as a dishwasher when detectives picked him up for questioning.

After several days in custody, Bedwell signed a confession on January 27, 1957, admitting he killed Barbara and Patricia with an accomplice named “Frank.”

As Bedwell told it, he and Frank met the girls at a Madison Street tavern on January 7. They spent a week together, shacking up at various hotels.

But on January 13, after the girls “resisted the men’s advances,” Bedwell and Frank knocked them unconscious, then dumped the sisters in a ditch.

“If I hadn’t been drinking, I wouldn’t have done what I done, and what I done I didn’t do intentionally,” he told the Chicago Daily Tribune.

Lorretta Grimes vehemently denied her daughters would carouse with disreputable men. “Our girls came from a good home and were brought up in religious surroundings,” she told the Chicago Daily Tribune.

Suppressing Evidence?

Almost immediately, holes started appearing in Bedwell’s story. Medical experts concluded the girls died December 28, 1956, and Bedwell’s factory timecard provided an alibi for the night they disappeared. His defense attorney insisted Bedwell’s confession was coerced.

Bedwell was released from jail on bond in February 5, 1957, to the chagrin of Cook County Sheriff Joseph Lohman and Glos, who believed he was responsible.

“I think it always bothered him. He was sure he had the right guy and didn’t like letting him go,” Glos’ daughter, Renee Glos-Block tells A&E True Crime.

On February 14, 1957, Glos took matters into his own hands. The larger than life, fedora-wearing “tough son of a gun” called a press conference at his family home, Glos-Block recalls.

Glos insisted the girls could not have died on December 28 and revealed lab results indicating Barbara had been sexually molested.

“He knew and believed the girls were both raped,” Glos-Block says. Harry Glos contended McCarron covered up evidence in deference to Lorretta and to keep the sisters’ reputations intact, she notes.

The coroner held his own press conference the next day and fired Glos, who continued to investigate the case.

‘Did You Hear About My Girls?’

After the Bedwell debacle, several suspects emerged but nothing stuck.

One was Charles Melquist, a suburbanite, found guilty in 1959 of murdering another girl, Bonnie Leigh Scott, 15. Her nude body was found November 1958 in a wooded area, a few miles from where the Grimes sisters died.

Authorities questioned Melquist about Barbara and Patricia after police found a list of girls, including young women from the Grimes’s neighborhood, at his apartment—but that was the extent of their inquiry.

Ray Johnson, a former police officer and lecturer who writes the “Chicago History Cop” blog, thinks Melquist played a role in the crime but was protected because of ties to the Chicago mob.

“Somebody still doesn’t want this case to be solved,” Johnson tells A&E True Crime. “I know there’s at least three people alive that know what happened that night.”

Another theory is that the sisters died after a liaison with teenage boys from a local gang who took them for a ride, then abandoned the two.

A local man told police he saw Barbara talking with youths in a car as Patricia watched, the night they went missing. One of the boys reportedly told Barbara, “You’ll be sorry,” the Chicago Tribune reported on February 14, 1957.

Some years after the tragedy, Forgala ran into Lorretta Grimes while shopping at a department store. Grimes recognized her and the two chatted, Forgala recounts.

One of the first things Grimes said was, “Did you hear about my girls?”

She died in 1989, never knowing what happened.

Related Features:

The Unsolved Rainbow Murders: What Happened to Vicki Durian and Nancy Santomero?

The Unsolved Delphi Murders: What Happened to Indiana Teens Libby German and Abby Williams?

A Lawyer Investigates the Depression-Era Child Murders in Her Family

Dick Kitchel: Exploring the Mysterious 1960s Unsolved Murder of an Oregon Teenager