To those outside her immediate family, Tylee Ryan’s last known whereabouts date to September 8, 2019, when the 17-year-old took a trip to Yellowstone National Park with her family. Ryan’s 7-year-old half-sibling, Joshua “JJ” Vallow, was last seen two weeks later, when his mother pulled him out of the local elementary school.

But it wasn’t until November 26, 2019—months after their disappearances—that local police realized the children were missing. Even then, they only learned of it when extended family asked law enforcement to check up on them.

The children’s mother, Lori Vallow, had gone to Hawaii with her new husband, Chad Daybell. In February 2020, she was charged with two felony counts of desertion and nonsupport of dependent children, resisting or obstructing officers, contempt of court and criminal solicitation to commit a crime.

In June 2020, the children’s remains were found buried on Daybell’s property. In August 2020 he pleaded not guilty to two felony counts of conspiracy to commit destruction, alteration, or concealment of evidence and two felony counts of destruction, alteration or concealment of evidence.

At the time of publication, neither Vallow nor Daybell have been charged in the children’s deaths. [Updates: On May 25, 2021, Vallow and Daybell were indicted on murder charges in the deaths of the children. On May 28, Vallow was ruled not competent to stand trial by a psychologist. However, a judge still needs to legally declare it and any pause in court proceedings could just be temporary. On May 12, 2023, Lori Vallow was found guilty on all counts of murdering her two children and also conspiring in the murder of Daybell’s ex-wife. On July 31, 2023 she received multiple life sentences without the possibility of parole.]

Brad Dennis, president of the KlaasKids Foundation—which works to prevent crimes against children—has worked on thousands of missing children cases. Dennis says that when those cases start with parental nonreporting and end with a child homicide victim, there’s usually a pretty straightforward explanation.

“One of the biggest reasons is that the parent is the perpetrator,” Dennis tells A&E True Crime. “For the most part, parents are very actively involved [in searching for their missing child]. But we occasionally get those [cases] where they are not as actively involved, and that immediately throws a spotlight on that family.”

Still, Dennis says, things are not always what they seem. Parents might not report their missing child for a myriad of reasons.

Immigration Concerns

For 22 years, she had no name. The remains of a little girl had been stuffed into a cooler and abandoned alongside a highway in uptown Manhattan. Police officers nicknamed the Jane Doe “Baby Hope” and were surprised when no one came forward to report the girl missing.

Years later, a tip led police to identify the child as 4-year-old Anjélica Castillo. But the perpetrator wasn’t a parent—it was Conrado Juarez, a restaurant worker whose sister had been caring for the child.

Investigators in that case believed the victim’s mother didn’t inform them about her missing child because many members of her family were undocumented.

Dennis says nonreporting of missing children can sometimes be more of an issue with immigrant families.

“I’ve had those cases, usually near border towns, or in border states,… [where] they’re scared to death to notify authorities because authorities will take one look at them and arrest them,” Dennis says. But, he adds, immigrants might not report for other reasons.

“There’s also a cultural thing,” Dennis says. “If they come from another country and law enforcement in their country [of origin] is very corrupt, there’ll be major trust issues with law enforcement. And so they’ll be used to trying to work things out within the family structure. They don’t know that they can trust our law enforcement [to help find the child].”

Guilt Within the Family

Sometimes, the parent won’t report their child missing because—even though they’re not the perpetrator—they know that the guilty party is another member of the family.

Wayne Sheppard, a retired member of Pennsylvania State Police who supervised the department’s Missing Persons Unit, says those types of situations came up frequently in his work.

“You could have a parent who kills and the other parent isn’t aware of it, but then becomes aware of it. But because of financial dependency issues [where] one [can’t tell] because of dependency on the money [from the other], they work together to…get rid of the body,” Sheppard says. “That’s not uncommon at all. And this [dynamic] extends to siblings as well.”

Outstanding Warrants

Sometimes the parents are guilty—they’re just not guilty of anything related to the child’s disappearance.

Dennis says that was the case with Shantara Hurry, the mother of 12-year-old Naomi Jones, who disappeared from the Aspen Village apartment complex in Pensacola, Florida—only to be found dead in a creek five days later.

Robert Howard, a convicted sex offender, was linked to the scene and awaits trial on first-degree murder. But before police even began their search, Hurry was detained for on an unrelated nonviolent offense.

“If a family member has some type of violation with law enforcement, then they’re going to be very hesitant to notify law enforcement to get involved with their child,” Dennis says.

The Missing Child Has a History of Running Away

Sometimes parents fail to report their older children as missing because the child has a history of running away, and they believe the child will eventually come home.

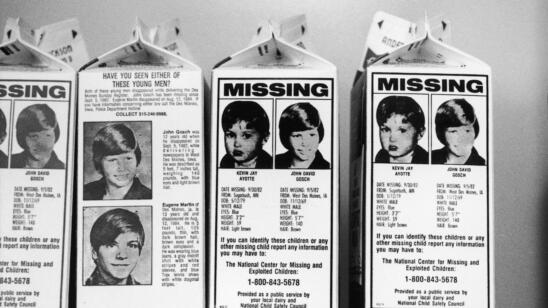

In June 2017, Robert Lowery of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children told A&E True Crime, “Unfortunately, the reality is that the older the child is, the assumption is the child is simply a runaway—that it’s the child’s behavioral problems.”

According to a 2013 U.S. Department of Justice missing children report, approximately 84 percent of the approximately 491,000 children who went missing that year were either runaways or throwaways (children who are told to leave the home and are prevented from returning without any alternative care provided). That number was largely unchanged from a similar report issued by the department in 1999.

Concern About Neighbors

While immigration status and strained relationships with law enforcement corresponds strongly with socio-economic circumstance, there’s one factor that Sheppard says cuts across all strata of society: concerns about what the neighbors might think.

“That issue runs across the entire spectrum,” Sheppard says. “You could have people living at poverty level or people who are affluent. They worry that people will say: ‘Why are police officers parked outside of [that family’s] house?'”

But none of those reasons is worth dwelling on long. When a child goes missing, the first hours are of vital importance.

According to a one national study of child abduction murders, in 76 percent of missing children homicide cases, the child was killed within three hours of abduction. That number jumped to 88.5 percent within 24 hours.

Both Sheppard and Dennis were also quick to note the damage caused by a commonly held myth—that you have to wait 24 hours before alerting authorities of a missing person. It’s not true.

“Every hour that a family member chooses not to report is hurting [the victim],” says Dennis. “You must notify law enforcement. Immediately.”

Related Features:

How Can Parents Protect Their Children From Online Predators